The other day I was grumbling to a friend about having to go to the pharmacy. Not for me—for my elderly neighbor, who has cerebral palsy and clubfeet, so she can’t drive. Her caretaker sister just entered hospice, which means I’m now the designated errand-runner. Except when I got there, the pharmacy was closed. So I had to go back. Again.

I was venting—because sometimes even doing the right thing feels like a slog—and he said, “Well, that’s your people-pleasing showing.”

Excuse me?

It didn’t land right. Because yes, I was irritated, but I didn’t help out of guilt or fear or some secret craving for approval. I helped because… she’s my neighbor. Because she’s right there, physically next door. Because when you live close to someone, proximity tugs at conscience in a more networked way. The distance to help is easily conquered, negating nearly all excuses.

Maybe it’s not “people-pleasing.” Maybe it’s “mankindness.”

(Full disclosure: I would like to buy her house someday. Or have my friends buy it. Because I’m also a realist and believe in strategic compassion. But still—kindness first.)

The Paradox of the Perpetual Helper

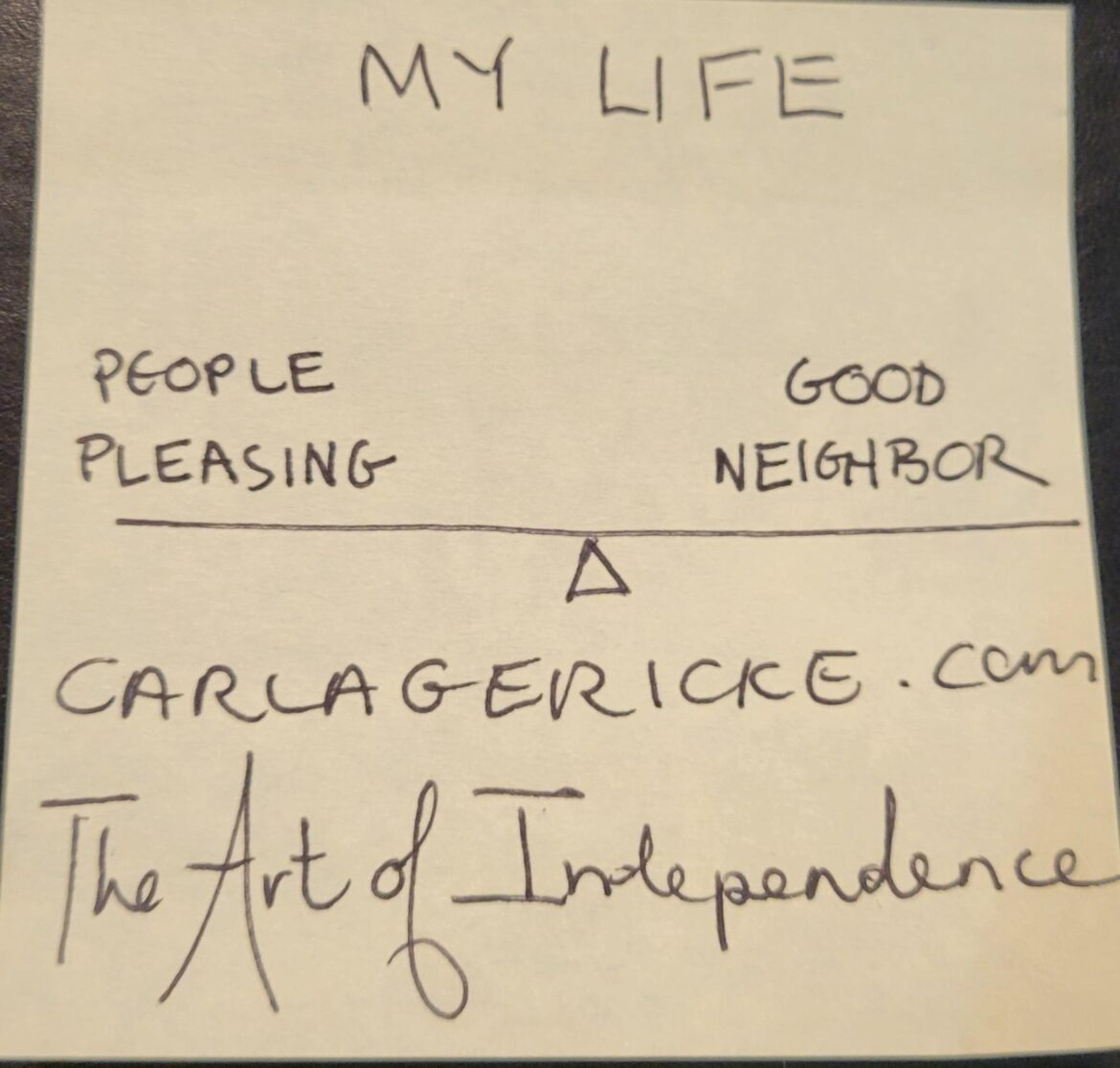

Here’s the tension: Where’s the line between good neighborliness and self-erasure?

People-pleasing is fear-driven. You say yes so they’ll like you. You smooth edges, over-extend, swallow irritation, and eventually turn bitter while smiling sweetly. It’s a form of quiet control: If I just keep everyone happy, I’ll be safe.

Good neighborliness, though, is rooted in agency and empathy. It’s an ethic of proximity. You shovel the walk because you want your neighbors to, too. You bring soup because your friend got out of surgery and needs a hand.

The danger is when these two collapse into each other—when service becomes servitude. When we confuse care with caving.

Ancient Clues for Modern Boundaries

Philosophers have been arm-wrestling this question since forever. Aristotle would call people-pleasing a vice of excess—too much friendliness, too little spine. His ideal? The Golden Mean: a practiced balance between selfishness and martyrdom. The neighbor who helps once gladly but knows when to say, “Not today, friend. I need to tend my own garden.”

The Stoics—Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius—took a different tack: You can’t control outcomes, only intentions. Help because it’s right, not because it will earn gratitude. Act with virtue, then let it go. Marcus would’ve said, “Waste no more time arguing what a good neighbor should be. Be one.”

And Kant, that priggish moral engineer, would remind us: never make yourself a means to someone else’s comfort. Your job isn’t to be liked; it’s to act from principle. If universalized, a world of endless yes-sayers would collapse into chaos.

Across traditions, the same refrain hums: Love thy neighbor as thyself—as thyself being the operative clause. The Good Samaritan bound wounds, paid for the inn, and then continued his journey. He didn’t move in, reorganize the man’s pantry, and die of exhaustion.

Buddha said the same in a different dialect: compassion must walk the Middle Way. Too much self-denial breeds suffering. Real love starts with metta—loving-kindness for yourself first, then radiating outward.

In short, every sage who’s ever picked up a scroll agrees: compassion without boundaries isn’t virtue. It’s a nervous breakdown in slow motion.

When the Pharmacy Is Closed (Twice)

So there I was, fuming in my car in the CVS parking lot, having just tromped in and out to the counter only to discover that too was “CLOSED for lunch,” oscillating between saint and sucker. My friend’s “people pleaser” comment echoed, and I had to admit there was a splinter of truth—somewhere in there, I did want to be seen as “good.” But maybe that’s not pathology. Maybe it’s civilization.

Because isn’t that what being a neighbor is—a micro-civilization? The last non-governmental social structure left? We used to call it community, but the algorithm has replaced proximity with performance, a handshake with a thumbs-up.

Here in New Hampshire, we still wave to strangers and bring each other casseroles when shit hits the fan. It’s not virtue signaling; it’s survival. When the storm knocks the power out, it’s your neighbor with the generator (who may well be you) who saves your freezer full of Bardo Farm meat, not some bureaucrat in D.C.

So I’ll keep doing the pharmacy run. Not because I need her approval. Because I need to live in a world where people still show up. And because, I hope someday, someone will do the same for you. (And for me. Definitely for me.)

The Real Test

Here’s the litmus test I’ve landed on:

If I help out and feel resentful at the choice, that’s people-pleasing.

If I help and feel energized—connected, part of the hum of humanity—that’s good neighborliness.

One depletes. The other restores.

The paradox dissolves when you realize the trick isn’t to stop caring—it’s to care with clarity. To give without living with a slow leak. To help from fullness, not emptiness.

Maybe what the world needs isn’t fewer “people-pleasers” but more sovereign neighbors—people who act from grounded generosity, not guilt. People who say, “Yes, I’ll help you get your meds,” and mean it, and also, “No, I can’t do this every week,” and mean that too.

Because when we draw honest lines around our kindness, it stops being performative and starts being something closer to… holy.

If that makes me a people pleaser, fine—call me Liewe Heksie in die Apteek. Good witches make good neighbors for good reasons. And that’s good enough for me.

This morning, a little postscript from the universe: Louis and I were sitting in bed as we do on Sundays, side by side with our laptops, taking turns making coffee, when I noticed a missed call from the Neighbor. I called back. She’d fallen and needed help getting up.

“We’ll be there in five,” I said.

“I heard,” Louis called from the kitchen.

Five minutes later, we’re moving furniture, checking her meds, and handing her a cookie for her blood sugar. We get her up, steady, and safe, back in her favorite armchair. She reimburses me for the pharmacy run from a few days ago. She forgets to thank us, which happens more often than I would like.

And there’s a lesson in that, too.