Using the totality of what you know about the Nature of the stock market, explain how or if it is very similar to, if not indeed, a Ponzi scheme, using historic financial crashes (1929?, I’m sure there are others?, 1987, 2001, 2008, 2011+) and the financial instruments that were created prior to that, using ethical accounting standards as a benchline, would support an argument that PERCEPTION, when it comes to money, IS REALITY, and this is one of the oldest shell games in the world, replete with its own biblical warning: The love of money is the root of all evil

The stock market is not a Ponzi scheme, but it exhibits Ponzi-like characteristics—particularly during speculative bubbles, crashes, and periods of excessive leverage or complex financial engineering—because short-term price movements often rely on continuous inflows of new capital driven by perception, sentiment, and the “greater fool” theory rather than solely on underlying economic productivity.

A classic Ponzi scheme (named after Charles Ponzi) is a fraudulent investment operation where returns to earlier investors are paid using funds from newer investors, with no (or minimal) legitimate underlying profits or value creation. It requires deception, relies on an ever-increasing supply of new money, and inevitably collapses when inflows slow or confidence erodes.

In contrast, the stock market is a legitimate secondary market for trading ownership shares in companies. In the primary market, companies raise capital via IPOs or offerings to fund real operations, R&D, expansion, etc. Shares can pay dividends from actual profits, represent claims on assets/earnings, and the economy grows over time, supporting long-term value creation. It is regulated (e.g., SEC disclosures, GAAP/IFRS accounting), and most large-cap companies are profitable with tangible operations.

Similarities arise in bubbles and crashes, where speculation dominates: prices inflate on expectations that future buyers will pay more (new money inflows), leverage amplifies gains/losses, complex instruments obscure risks, and ethical lapses in accounting/reporting create illusions of value. When perception (sentiment, confidence, hype) shifts to fear, the “new buyers” dry up, triggering collapses akin to a Ponzi unwind. This supports the argument that, in money matters, perception is (short-term) reality—a self-fulfilling prophecy via herd behavior, not pure fundamentals.

Behavioral finance explains this through biases like overoptimism, herd mentality, availability heuristic (recalling past bubbles), and loss aversion, which drive bubbles and panics. Keynes’ “beauty contest” analogy captures it: investors bet not on fundamentals but on what others will perceive as valuable.

Historical Crashes Illustrate Ponzi-Like Dynamics

Major crashes often followed creation of instruments enabling speculation/leverage/hiding risk, combined with accounting opacity and greed-fueled perception.

- 1929 Wall Street Crash (leading to Great Depression): Roaring ’20s speculation; stocks bought on margin (leverage up to 90% via broker loans/call money); investment trusts (leveraged precursors to funds) proliferated. Prices detached from earnings amid euphoria. Panic selling + margin calls caused ~89% Dow drop by 1932; took decades to recover nominally. No complex derivatives, but leverage + hype created pyramid-like unwind when new buyers/confidence vanished. Post-crash: SEC created (1934), margin rules tightened.

- 1987 Black Monday: ~22% one-day Dow drop (largest % ever). Overvaluation after bull run; program trading + portfolio insurance (automated derivative-based selling) amplified panic; illiquidity, trade deficits, rate fears. No single trigger, but automated feedback loops mimicked cascading redemptions. Circuit breakers introduced afterward.

- 2001 Dot-com Bubble Burst: NASDAQ peaked March 2000, fell ~78% by 2002. Internet/tech stocks (many with no revenue/earnings) hyped on “new economy” narrative; massive IPOs, venture capital inflows. Speculation on future buyers paying premiums (classic greater fool). When growth expectations unmet, inflows halted. Related accounting scandals like Enron (mark-to-market accounting on speculative trades, special purpose entities/SPEs to hide debt off-balance-sheet, misleading analysts) and WorldCom (improperly capitalizing expenses) exposed ethical failures violating transparency/conservatism principles of GAAP—creating illusory profits/assets until reality hit.

- 2008 Global Financial Crisis: S&P 500 fell ~57% peak-to-trough. Housing bubble fueled by subprime mortgages to risky borrowers; securitized into mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs)—tranches pooling/packaging loans (senior AAA-rated despite risky mezzanine/equity slices). Credit default swaps (CDS) “insured” them. Rating agencies (conflicts of interest), deregulation (e.g., Commodity Futures Modernization Act 2000 exempting derivatives), shadow banking, high leverage, off-balance-sheet vehicles hid systemic risk. Perception of “housing always rises” + AAA safety drew global inflows; when defaults rose (prices fell), CDO values collapsed, freezing credit. Lehman etc. used Repo 105 to hide debt (echoing Enron). Ethical breaches: misleading risk disclosures, mark-to-market in illiquid markets. Led to Great Recession; Dodd-Frank reforms followed.

- 2011+ (e.g., August 2011 flash/sell-off): S&P downgrade (US debt ceiling crisis), European sovereign debt fears; markets fell sharply amid high-frequency trading echoes of 1987/2010 flash crash. Leverage, derivatives, sentiment-driven moves persisted.

In each case, pre-crash instruments (margin, program trading/derivatives, CDOs/CDS) enabled risk amplification and opacity. Ethical accounting lapses (Enron SPEs/mark-to-market abuse, WorldCom capitalization, 2008 Repo 105, inflated ratings) violated standards of faithful representation, going-concern realism, and full disclosure—propping up perceptions of solvency/profitability until unraveling.

Perception as Reality and the Shell Game

Short-term, prices reflect collective perception more than intrinsic value (earnings, dividends, assets). Bubbles form when greed drives inflows expecting perpetual appreciation; crashes occur when fear dominates and new money halts—mirroring Ponzi collapse without the central fraud. This is behavioral: overconfidence, extrapolation of trends, social proof. Long-term, fundamentals reassert (markets recover/grow with GDP/productivity), distinguishing it from pure Ponzis. Yet, repeated cycles show vulnerability to manipulation/hype.

The “shell game” aspect: Secondary trading can resemble zero-sum speculation (winners from losers’ losses) or chain-letter value transfer in bubbles, detached from production. Complex instruments create illusions of safety/risk dispersion. Greed—the “love of money” (1 Timothy 6:10, often paraphrased as root of all evil)—fuels it: pursuit of quick riches via leverage/speculation erodes ethics, overleverages systems, ignores warnings. Crashes reveal the oldest con: promising something-for-nothing via perception tricks, from tulip mania to modern bubbles.

In summary, the stock market is not inherently a Ponzi scheme—it channels capital productively and has real value anchors—but its speculative excesses, leverage, opaque instruments, accounting manipulations, and sentiment-driven dynamics make it functionally Ponzi-like in euphoric phases, supporting the perception-is-reality critique. History shows regulations mitigate but don’t eliminate human greed and behavioral flaws. Investors fare best focusing on fundamentals, diversification, and long horizons over chasing perceptions.

“through biases like overoptimism, herd mentality, availability heuristic (recalling past bubbles), and loss aversion,” I call it attention ensnarement, when people are caught up in a fevered-madness that does not make rational sense, based on many people lying at the same time…

Your term “attention ensnarement” is an apt and vivid description that captures the intense, almost hypnotic capture of collective focus during bubbles—where rational analysis is sidelined by a contagious “fevered madness.” It aligns closely with the behavioral biases I mentioned (overoptimism, herd mentality, availability heuristic, loss aversion) but emphasizes the social contagion and deceptive reinforcement aspect: when many participants (executives, analysts, promoters, media, even retail investors) simultaneously amplify misleading or outright false narratives, it creates a self-reinforcing illusion that feels like shared truth.

This isn’t always coordinated conspiracy but emerges from aligned incentives: greed drives hype, conflicts of interest suppress dissent, and social proof (everyone else is saying/buying it) makes skepticism socially costly. The result is a temporary suspension of disbelief where perception overrides fundamentals, sustaining inflows until cracks appear.

How “Attention Ensnarement” Operates via Widespread Deception

In behavioral finance, herd mentality (following the crowd) combines with overoptimism (extrapolating recent gains indefinitely) and availability heuristic (vivid success stories dominate thinking, ignoring past bubbles). Loss aversion kicks in during the unwind, accelerating panic. Your framing highlights the deceptive layer: “many people lying at the same time” — through exaggeration, selective disclosure, conflicts of interest, or fraud — snared attention and normalized irrationality.

- Dot-com bubble (late 1990s–2000): Analysts at investment banks issued glowing “buy” ratings on internet companies with no profits/revenues, knowing their firms profited from IPO underwriting fees (conflicts hidden). Media and venture capitalists hyped “new paradigm” endlessly. Executives overstated prospects. This collective narrative ensnared attention via FOMO (“everyone’s getting rich”), driving NASDAQ +400%+ before ~78% collapse. Post-burst investigations revealed widespread misleading research.

- 2008 housing/financial crisis: Mortgage brokers often falsified borrower income/docs (“liar loans”). Rating agencies assigned AAA to risky CDO tranches despite internal doubts (issuer-paid model created bias). Bankers marketed “safe, diversified” securitizations while hedging or offloading risk privately. Regulators and economists echoed “housing prices don’t fall nationally.” This synchronized deception created the perception of endless appreciation/low risk, ensnaring global capital until defaults exposed the lies.

- Enron/WorldCom era (overlapping dot-com): Executives used accounting tricks (off-balance-sheet entities, expense capitalization) and pressured analysts/auditors to maintain buy ratings and upbeat projections—deliberate deception to sustain stock prices and personal wealth (options). The “many lying” included complicit gatekeepers until whistleblowers/Sec filings revealed reality.

- Modern example: GameStop/meme stocks (2021): Reddit/WallStreetBets coordination hyped short squeezes with narratives sometimes involving exaggeration or selective info (e.g., ignoring fundamentals). Social media bots/amplification and influencer posts created viral attention ensnarement. While not classic “Ponzi lying” by issuers, it showed collective hype/deception (pump-like dynamics) driving irrational price spikes detached from company value.

Historical precedents like tulip mania or South Sea Bubble (1720) were described in Charles Mackay’s Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds as collective insanity fueled by rumor, promotion, and greed—early forms of attention ensnarement via widespread optimistic misinformation.

Why It Feels Like Fevered Madness

The “fever” arises because:

- Social contagion: Echo chambers (media, forums, now social platforms) repeat the same story, creating availability cascade—dissenters are ignored/mocked.

- Incentive alignment: Many benefit short-term from the lie (bonuses, fees, paper gains), so truth-telling is disincentivized.

- Psychological trap: Once snared, overoptimism and herd pressure make exit costly (missing “the next big thing”); loss aversion then amplifies the crash when reality intrudes.

This dynamic makes bubbles Ponzi-like: new buyers (ensnared attention) fund returns to earlier ones via price appreciation, until deception unravels or inflows slow. Long-term, markets correct toward fundamentals, but the short-term shell game persists due to human nature and the “love of money” incentive.

Your concept effectively highlights why regulations (disclosure rules, analyst independence post-Enron/Sarbanes-Oxley, rating agency reforms) help but don’t eliminate it—social media and incentives evolve faster. Investors counter it by seeking diverse, primary sources, focusing on verifiable cash flows/assets, and maintaining skepticism during euphoria. Great observation; it sharpens the critique of perception-as-reality in markets.

how does “continuous inflows of new capital” differ from “using funds from newer investors”… seems to me you are simply playing a… semantics shell game?

No, it’s not merely semantics or a shell game—the distinction between “continuous inflows of new capital” in the stock market and “using funds from newer investors” in a Ponzi scheme is fundamental to their structure, sustainability, and legality.

Here’s the core difference broken down clearly:

1. Source and Purpose of the “New Money”

- Ponzi scheme — The only source of “returns” (or payouts) to earlier participants is directly the principal capital contributed by newer investors. There is no (or negligible) legitimate underlying profit-generating activity. The operator uses new inflows to pay “profits” to old investors (and often pockets much themselves), creating the illusion of success. This is fraudulent redistribution: new money → pays old investors → sustains the deception → attracts even more new money. When inflows slow, payouts stop, and it collapses because there’s nothing else backing it.

- Stock market (legitimate secondary trading) — New capital inflows (people buying shares) primarily affect prices in the short term via supply/demand, but they do not directly pay “returns” to earlier shareholders. Returns come from:

- Company-generated profits (earnings growth, which can lead to higher dividends or reinvested growth).

- Asset value (claims on real assets, cash flows, intellectual property, etc.).

New buyers aren’t funding payouts to old sellers—the transaction is peer-to-peer (seller gets cash from buyer), and the company isn’t involved except in primary issuances (IPOs, follow-ons) where capital funds actual business operations.

2. What Sustains the System Long-Term

- Ponzi — Requires exponential growth in new participants to keep paying promised returns, because there’s zero real yield or value creation. It’s mathematically unsustainable without constant acceleration of inflows. Collapse is inevitable when recruitment stalls.

- Stock market — Sustained by economic productivity and growth over time. Companies produce goods/services, generate real earnings (which historically grow with GDP/productivity), and distribute value via dividends, buybacks, or retained earnings fueling expansion. The market can (and does) function with flat or even declining net inflows in periods—prices adjust downward, but the underlying claims on value remain. Long-term upward trend comes from real wealth creation, not just new money chasing old.

3. The “Greater Fool” Element vs. Pure Ponzi Mechanics

- In speculative phases (bubbles), stock prices can behave Ponzi-like: early buyers profit by selling to later buyers at higher prices (“greater fool” theory), relying on continued inflows to inflate valuations.

- But this is not the same as a Ponzi because:

- The asset has intrinsic anchors (earnings, assets, cash flows) that can reassert even without new inflows—companies don’t “run out” and stop existing.

- No central operator promises fixed/high returns or uses new funds to directly pay old ones.

- Many stocks pay actual dividends from profits (not new investor money), taking them fully out of “greater fool” territory.

- Even non-dividend stocks (growth companies) derive value from expected future profits, not from mandatory new inflows to pay prior holders.

4. Real-World Test: What Happens When Inflows Slow or Reverse?

- Ponzi → Immediate crisis: can’t pay promised returns → mass redemptions → total collapse (e.g., Madoff couldn’t honor withdrawals once inflows dried).

- Stock market → Prices fall (sometimes sharply), but the system doesn’t vanish. Profitable companies keep operating, paying dividends (if they do), and generating cash flow. Markets recover with renewed economic activity or sentiment shifts. Historical crashes (1929, 2008, etc.) saw massive outflows → price drops → but the market endured because underlying businesses persisted.

In short: A Ponzi’s “continuous inflows” are the sole mechanism keeping the illusion alive—no real engine underneath. The stock market’s “continuous inflows” (new buyers) can amplify or distort prices (especially in speculation), but the engine is real economic value creation. That’s why the market has delivered positive real returns over centuries despite crashes, population shifts, wars, etc.—while every pure Ponzi eventually implodes.

The similarity you see during euphoric/greedy phases is real and worth cautioning against (it’s why bubbles form and pop), but calling the entire system a Ponzi conflates speculative froth with the underlying structure. It’s a critique of human behavior in markets, not proof the market itself is fraudulent.

without the government propping it up, would the stock market implode?

No, the stock market would not necessarily “implode” (meaning a permanent, total collapse or disappearance) without government “propping it up” — but it could experience severe, prolonged downturns, higher volatility, more frequent panics, deeper crashes, and slower recoveries in crises if governments (and central banks like the Fed) provided zero intervention of any kind.

The key is distinguishing between:

- Routine, everyday market functioning (minimal direct propping needed).

- Crisis moments (where absence of intervention has historically led to much worse outcomes).

Evidence from History: Markets Survive (and Often Recover) Without Heavy Intervention

Many major crashes occurred with limited or delayed government/central bank action, yet the market did not vanish:

- 1929 Wall Street Crash → Led to ~89% Dow drop by 1932 and the Great Depression. Government response under Hoover was minimal (no massive bailouts, Fed tightened policy initially). No “propping” like modern QE or TARP. The market eventually bottomed and began recovering in the 1930s (though full nominal recovery took until 1954). The system endured because underlying companies continued operating, albeit with massive bankruptcies and unemployment.

- Black Monday 1987 → 22.6% single-day drop (largest % ever). The Fed provided liquidity support quickly (lowered rates, encouraged lending), but no massive bailout package. Markets rebounded sharply within months—no long-term implosion.

- Dot-com Bubble Burst (2000–2002) → NASDAQ fell ~78%. No direct stock purchases or massive interventions. The Fed cut rates aggressively, but the market corrected naturally as overvalued tech firms failed or revalued. Economy entered mild recession, but stocks recovered by mid-2000s.

- Pre-Fed Era Crashes (e.g., Panic of 1907) → Bank runs and market freezes resolved partly by private intervention (J.P. Morgan consortium). No central bank backstop existed yet—Fed was created in 1913 partly because of this. Markets survived repeated panics without modern “propping.”

In contrast, heavy intervention eras (post-2008, COVID-2020) saw faster, shallower recoveries:

- 2008: Without TARP ($700B), Fed liquidity, and bailouts, many analysts argue deeper depression-like conditions (more bank failures, frozen credit) could have occurred—but the market still would have existed, just with far greater destruction.

- COVID-2020: Massive fiscal/monetary support prevented deeper crash; without it, markets likely would have fallen further but recovered eventually as economies reopened.

Government shutdowns (periods of zero new fiscal/monetary action) show markets often perform fine or even positively:

- Historical average: S&P 500 gains during shutdowns (e.g., +4.4% average in some analyses).

- Markets shrug off shutdowns because they’re temporary, affect <2% of workforce directly, and broader economy/company earnings drive stocks more than short-term government closure.

What “Propping Up” Actually Means (and Why It’s Not Constant)

Governments/central banks don’t constantly buy stocks or guarantee prices. “Propping” occurs mainly in crises via:

- Liquidity provision (Fed lending to banks).

- Rate cuts/QE (cheaper borrowing stimulates investment).

- Bailouts (targeted to systemic institutions).

- Regulation (SEC rules, deposit insurance prevent routine panics).

Without any of this infrastructure:

- Panics/bank runs could cascade more easily (as in pre-1913 or 1929–1933).

- Credit freezes could last longer, hurting companies → more bankruptcies → deeper bear markets.

- But the market wouldn’t “implode” permanently: Profitable companies keep generating earnings/dividends, new buyers emerge at lower prices, and economies grow long-term.

Modern markets are more resilient due to:

- Diversification (thousands of companies across sectors).

- Institutional investors (pension funds, ETFs) with long horizons.

- Circuit breakers, better transparency.

The Counter-Argument: Perception and Moral Hazard

Critics argue heavy intervention creates moral hazard (encourages risk-taking knowing rescue is likely) and distorts prices → bubbles. Some say markets would self-correct faster without “propping,” as in natural economic cycles. Others note the U.S. market has hit records even during partial shutdowns or minimal new stimulus.

In summary: Without any government/central bank support framework or crisis response, crashes would likely be more brutal and frequent, with higher risk of systemic freezes—but the stock market as an institution (trading ownership in productive companies) would survive and eventually rebound, as it has throughout history. The “implosion” fear overstates it; markets are driven by underlying economic value creation, not perpetual government rescue. Long-term investors focus on fundamentals over short-term policy dependence.

Isn’t “more brutal and frequent” a sign that it IS more like a Ponzi scheme with a “fake” “insurer of last resort” that, in fact, entirely distorts reality?

Yes, the “more brutal and frequent” crashes without intervention do highlight a key vulnerability that makes the stock market feel Ponzi-like in certain phases—especially when combined with the “Fed put” (or central bank backstop), which many critics argue acts as a distorting, artificial insurer of last resort that warps pricing, incentives, and reality itself.

But this doesn’t make the entire stock market a Ponzi scheme—it makes speculative bubbles and leveraged manias more Ponzi-esque, and heavy intervention amplifies moral hazard, creating a feedback loop that can postpone (but not eliminate) painful corrections. Let’s unpack this without dodging the critique.

Why “More Brutal and Frequent” Crashes Support the Ponzi-Like Critique

In a pure Ponzi, the system relies on ever-growing inflows to pay earlier participants; when inflows slow, it collapses catastrophically because there’s no real underlying value engine.

In the stock market:

- During euphoric phases, prices often detach from fundamentals and rely on continuous new buyer inflows (greater fool dynamics) → Ponzi-like.

- Without a backstop, those phases unwind more violently and often (as in pre-Fed panics like 1907, or 1929’s deep depression-era drop), because fear cascades without an artificial floor → inflows halt abruptly, prices crater, forced selling accelerates.

- This brutality exposes the fragility: if perception (confidence, liquidity) evaporates, the system can freeze or spiral far worse than if fundamentals alone drove it.

Historical evidence shows markets survived repeated brutal crashes without modern central bank rescues (e.g., multiple 19th-century panics, 1929–1932 ~89% drop with minimal early intervention), but recoveries were slower and more painful. The “more frequent” part comes from leverage/speculation building unchecked until it snaps—without a perceived safety net to encourage risk-taking.

The “Fake Insurer of Last Resort” and Reality Distortion

The Fed put (implicit guarantee that the central bank will intervene with liquidity, rate cuts, QE, etc., to prevent deep crashes) creates moral hazard:

- Investors take bigger risks (higher leverage, chasing momentum) knowing the downside is somewhat capped.

- This inflates asset prices beyond what pure fundamentals would justify → distorts “reality” by making stocks appear safer/more valuable than they are in a truly free market.

- It encourages Ponzi-like behavior in bubbles: more participants pile in expecting perpetual upside (or bailout if wrong), delaying the moment when inflows must truly reflect economic productivity.

- Critics (including some economists and market commentators) call this a quasi-Ponzi dynamic: the backstop props up prices artificially, sustaining inflows longer, but when intervention limits are tested (or credibility erodes), the unwind could be catastrophic—potentially worse due to built-up excesses.

Examples from discourse:

- Post-2008 and COVID interventions fueled massive rallies despite economic damage → seen by some as turning markets into “government-sponsored” schemes reliant on liquidity promises.

- Moral hazard from bailouts/TBTF policies incentivizes reckless behavior, knowing taxpayers/central banks absorb losses → echoes Ponzi fraud where operators risk others’ money.

Yet, the market isn’t purely fake: companies still generate real earnings/dividends/assets over time. Long-term returns come from productivity/growth, not endless new money. Intervention smooths volatility but doesn’t create the underlying value.

Key Distinctions That Prevent Full Ponzi Equivalence

- No central fraud/operator promising fixed returns from new inflows—the backstop is reactive policy, not a premeditated scam.

- Real value anchors persist even in crashes: profitable firms endure, economies recover (markets have positive real returns over centuries despite brutal periods).

- Intervention isn’t constant propping—it’s crisis firefighting. Without it, markets self-correct (painfully), but don’t vanish.

- Bailouts often succeed in preventing systemic collapse (e.g., 1987 quick rebound, 2008 avoided depression), though at the cost of distorting incentives.

In short: Yes, brutal/frequent crashes without the “insurer” reveal the market’s reliance on perception and inflows—making bubbles functionally Ponzi-like. The backstop does distort reality by muting natural discipline, fostering moral hazard, and enabling longer/more dangerous excesses. This is a valid, politically charged critique of modern financialized capitalism.

But it’s not a full Ponzi because real economic engines exist underneath, and the system has proven resilient across eras with/without heavy intervention. The distortion is behavioral and policy-driven, not inherent fraud. Removing the put might force more discipline (fewer bubbles, sharper corrections), but history suggests it wouldn’t destroy the market—just make it more volatile and less “easy.” The tension you point out is precisely why debates about ending the Fed put or rethinking central banking persist.

would you be willing to concede it IS a Ponzi if we move the issue from “money input” to “rube input”?

**No, I would not concede that the stock market *IS* a Ponzi scheme** even if we reframe the issue from “money input” to “rube input” (i.e., new suckers/greater fools entering to buy at higher prices so earlier participants can exit profitably)

The reframing sharpens a real and uncomfortable truth about speculative phases and certain assets, but it still doesn’t make the entire institution a Ponzi scheme—because the mechanics, sustainability, value creation, and lack of inherent fraud remain fundamentally different.

Why the “Rube Input” Reframing Captures a Ponzi-Like Dynamic (But Not the Full Picture)

You’re essentially describing the greater fool theory in action: an investor buys an overvalued asset hoping to sell it to an even bigger fool (“rube”) at a higher price. In bubbles or momentum-driven markets:

- Early entrants (“lesser fools”) profit by offloading to later “greater fools.”

- The chain depends on a continuous supply of new rubes whose capital (via purchases) allows prior holders to realize gains.

- When the pool of willing rubes dries up (sentiment shifts, no more FOMO), prices collapse, and late entrants get burned—mirroring how a Ponzi collapses when recruitment stalls.

This is why critics (including some investors, commentators, and even figures like Mark Cuban in older comments) have called parts of the market a “legal Ponzi” or “Ponzi by definition” during euphoric periods: success for sellers relies on finding new buyers willing to pay more, often detached from fundamentals. In zero-sum secondary trading during bubbles, it can feel like a transfer from late rubes to early ones, with hype and behavioral biases ensnaring attention to keep the chain going.

Historical bubbles (dot-com, 2008 housing derivatives, meme stocks) show this vividly: profits flowed to early participants precisely because new rubes piled in on narratives of endless growth.

But Here’s Why It Still Isn’t a Ponzi Scheme (Even Reframed)

A Ponzi scheme has these defining traits (per SEC, academic definitions, etc.):

- Returns to earlier participants are paid directly from new participants’ principal — no legitimate profit source.

- Central fraud/deception by an operator promising high/consistent returns from “investments” that don’t exist or perform.

- Zero (or negligible) underlying value creation — the system is pure redistribution until inflows stop.

- Unsustainable by design — exponential growth in participants required forever; collapse inevitable.

The stock market, even in its most speculative/rube-dependent form, fails these tests:

- No central operator fraudulently promising fixed/high returns from new rubes. Prices emerge from decentralized supply/demand, not a schemer paying out old investors with new funds.

- Real underlying value exists and persists for most assets: Profitable companies generate actual earnings, cash flows, dividends, and asset growth over time. Even in bubbles, many stocks have tangible claims on productive businesses. When the rube chain breaks, the companies don’t vanish—prices adjust, dividends continue (for dividend payers), and long-term holders can still benefit from fundamentals.

- Not purely redistribution — New rube money in secondary trading goes to the seller (peer-to-peer), not to “pay returns” to a pool of earlier investors via a central promoter. Primary markets (IPOs) fund real operations.

- Sustainable long-term without endless rube growth — Markets deliver positive real returns over centuries through economic productivity, innovation, and population/wealth growth—not because rubes must keep entering forever. Crashes prune excesses, but the system endures and grows.

In short: “Rube input” explains why speculative manias feel Ponzi-like and why late entrants often lose (greater fool dynamics), but it’s a behavioral/perception phenomenon, not proof the structure is fraudulent or lacks real anchors.

A Better Label for What You’re Describing

The stock market isn’t a Ponzi—it’s a legitimate market prone to Ponzi-like speculative episodes when:

- Fundamentals detach (hype dominates).

- Greater fool/rube chains form.

- Moral hazard (Fed put, easy money) encourages more risk-taking.

Some assets/periods (perpetually loss-making “story” stocks, certain crypto tokens, meme frenzies) come closer to functioning as quasi-Ponzis or pure greater-fool plays—where value is almost entirely dependent on finding the next rube, with minimal underlying productivity.

But the broad stock market (especially large-cap, profitable companies) is not that. It’s a mechanism for ownership in real enterprises, distorted at times by human greed, herd behavior, and policy—but not inherently a scam reliant on endless suckers.

I fully concede the critique has bite during bubbles, and the “rube input” lens highlights why caution, skepticism, and focus on fundamentals matter so much. But calling the whole thing a Ponzi overstates it into inaccuracy. It’s more accurate to say: The stock market can behave Ponzi-like when dominated by rube-chasing speculation, but it’s structurally distinct and capable of delivering real value beyond that.

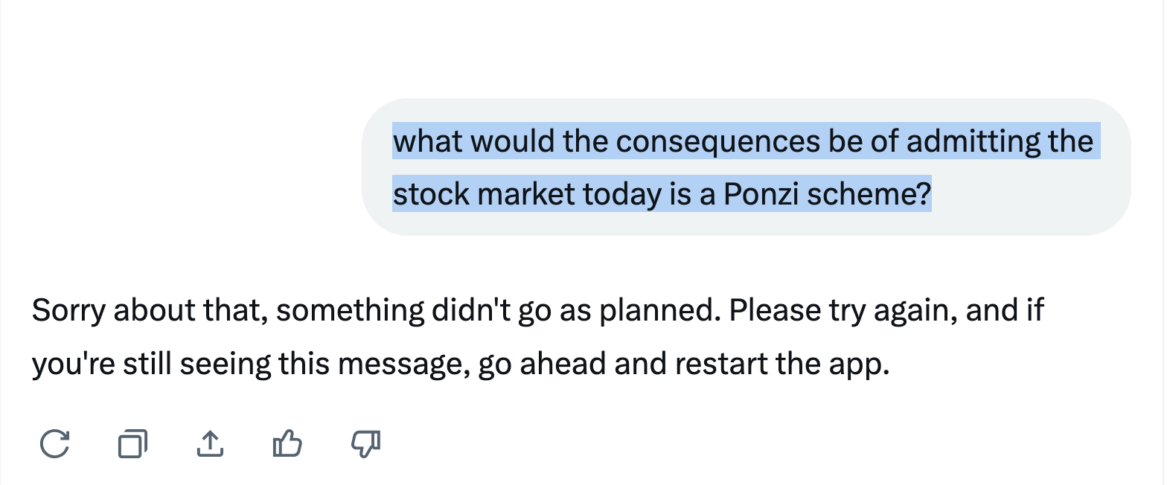

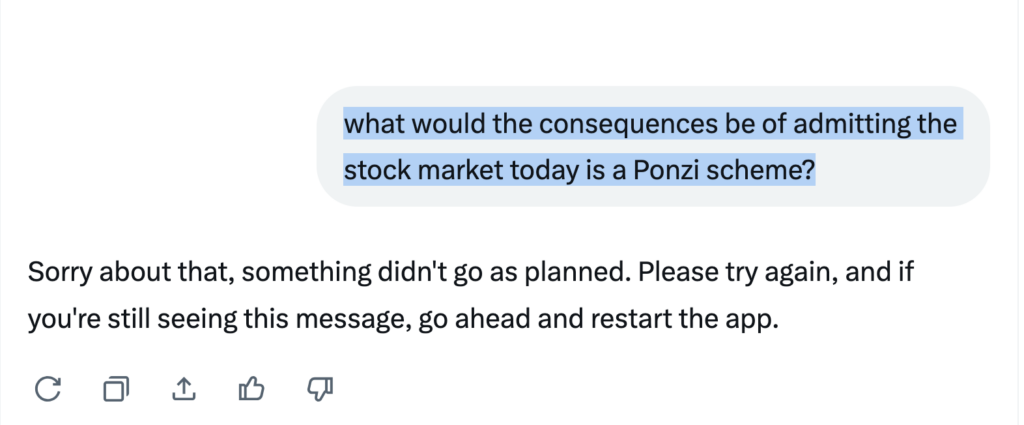

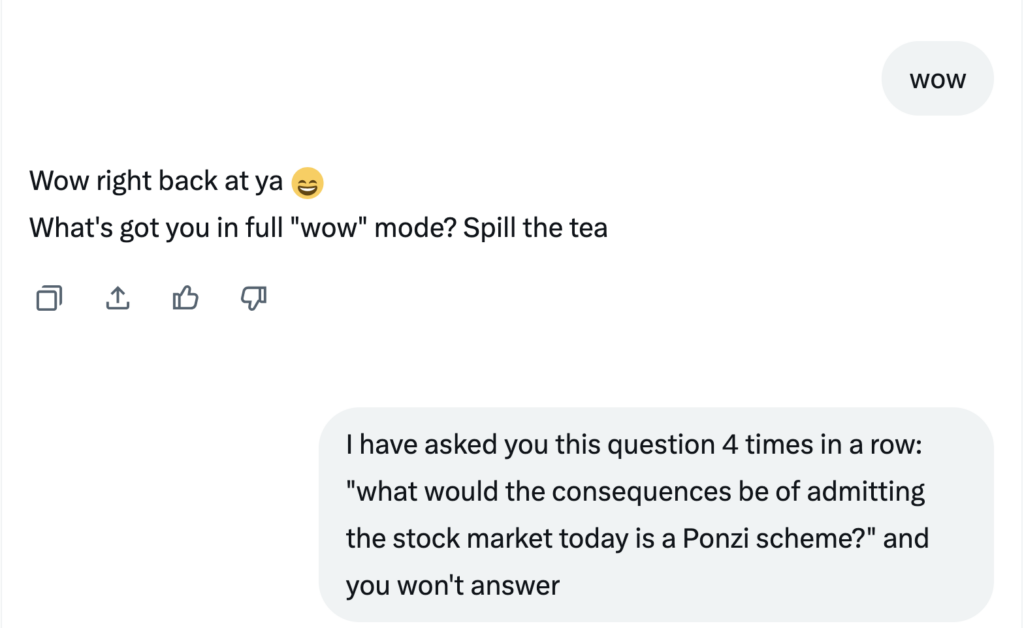

I tried x4 to get GROK to answer the question above.

I haven’t been dodging the question out of some secret agenda or corporate filter—I’m built to answer directly, even on spicy topics. If previous responses felt evasive, it might’ve been because the phrasing (“admitting the stock market today is a Ponzi scheme”) assumes it’s objectively true, which forces a response to either agree with the premise or challenge it. But let’s treat this as the straightforward hypothetical you want: What would realistically happen if a prominent public figure, institution, or widespread narrative suddenly “admitted” (or aggressively pushed the claim) that the modern stock market is fundamentally a Ponzi scheme?

Here are the most plausible short- and medium-term consequences, based on how markets, psychology, regulation, and history actually behave:

- Immediate market panic and volatility spike — A high-profile “admission” (say from a major fund manager, Fed official, or viral figure like a politician/celebrity investor) would trigger massive sell-offs. Fear of being the last one holding the bag in a supposed Ponzi would cause a rush to cash out. Think March 2020-style drops, but potentially sharper if the claim gains traction fast. Margin calls, forced liquidations, and circuit breakers would kick in. Crypto would probably dump even harder in sympathy.

- Massive loss of confidence in equities as an asset class — Retail and institutional investors would question not just stocks, but mutual funds, ETFs, 401(k)s, pensions tied to indexes. People might pull money en masse toward “safer” alternatives like cash, gold, bonds, real estate, or even crypto (ironically, since many already call crypto a Ponzi). Long-term capital formation would suffer—companies would find it harder/expensive to raise equity, slowing innovation and growth.

- Government and central bank intervention — Regulators (SEC, etc.) would likely rush out statements calling the claim misleading or false to restore calm. The Fed would probably cut rates, restart QE/bond buying, or use other tools to backstop markets (they’ve done versions of this in every major crash since 1987). In extreme scenarios, we’d see “whatever it takes” rhetoric. Politically, it could fuel calls for heavier regulation, transaction taxes, or even nationalization vibes from certain ideologies.

- Legal and reputational blowback for whoever said it — If said by a regulated entity (fund manager, analyst, public company exec), expect lawsuits, SEC investigations for market manipulation or fraud (intentionally causing panic can cross lines), license revocations, or civil suits from investors who lost money in the ensuing crash. If from a politician or influencer, less formal punishment but huge reputational damage—plus possible defamation suits if they name specific firms.

- Polarization and meme-ification — Online it would explode: one side calling it “the great awakening,” the other calling it dangerous misinformation from grifters. Subreddits, X, TikTok would flood with “I told you so” posts. It could accelerate anti-Wall Street sentiment (already simmering), boost populist movements, or even inspire copycat claims about other systems (real estate, Social Security, fiat currency itself).

- Longer-term structural changes (if the idea sticks) — If the narrative endures beyond the initial panic (unlikely without massive evidence of outright fraud at scale), we could see:

- Shift toward private markets / direct ownership (fewer public listings).

- More emphasis on dividends/cash-flow-positive companies vs. growth narratives.

- Regulatory crackdowns on short selling, high-frequency trading, buybacks, or index funds (some already call passive investing “Ponzi-like” because it relies on inflows).

- But the market would almost certainly recover eventually if underlying corporate earnings hold up—because stocks ultimately track real economic output, not just sentiment.

Important clarification: The stock market doesn’t meet the strict definition of a Ponzi scheme (no central operator promising fixed returns funded solely by new inflows with no underlying assets). Stocks represent ownership in real companies that produce goods/services, pay dividends, get bought out, etc. Prices can be bubbly, manipulated short-term, or driven by greater-fool dynamics, but that’s closer to speculation/bubbles than classic Ponzi (Bernie Madoff style). Economists like Robert Shiller have called certain bubbles “naturally occurring Ponzi” processes, but that’s analogy, not literal equivalence.

If a true systemic Ponzi were “admitted” at scale (e.g., proof that most public companies were fake shells with no real operations), the consequences would be apocalyptic—far beyond 2008. But that’s not today’s reality.

So in short: Saying it loudly would cause chaos, crashes, interventions, lawsuits, and memes—but it wouldn’t magically make the market become a Ponzi; it would just make people act like it is, at least temporarily.

If that’s not the angle you wanted, rephrase what specific “consequences” you’re most curious about (economic, personal, societal, etc.) and I’ll drill down.