The online disinhibition effect is a psychological phenomenon where people behave more freely, impulsively, or aggressively online than they would in face-to-face interactions. Coined by psychologist John Suler in his 2004 paper, “The Online Disinhibition Effect,” it explains why the internet can bring out both the best and worst in people, particularly when anonymity or pseudonymity is involved. If you’re trying to persuade people you know who exhibit negative behaviors online due to this effect, understanding its causes and tailoring your approach to their motivations can help. Below, I’ll break down the effect, its drivers, and practical strategies to encourage better online behavior, connecting it to the context of pseudonyms like those in the tweet you mentioned.

What is the Online Disinhibition Effect?

The online disinhibition effect describes how digital environments lower psychological barriers, leading to behaviors that range from overly candid or empathetic to hostile or toxic. Suler identifies two types:

- Benign Disinhibition: People share personal thoughts, emotions, or vulnerabilities they’d hesitate to express in person. For example, someone might open up about mental health struggles on an anonymous forum like Reddit.

- Toxic Disinhibition: People engage in aggressive, cruel, or inappropriate behavior, like trolling, cyberbullying, or hate speech, often feeling shielded by the lack of real-world consequences.

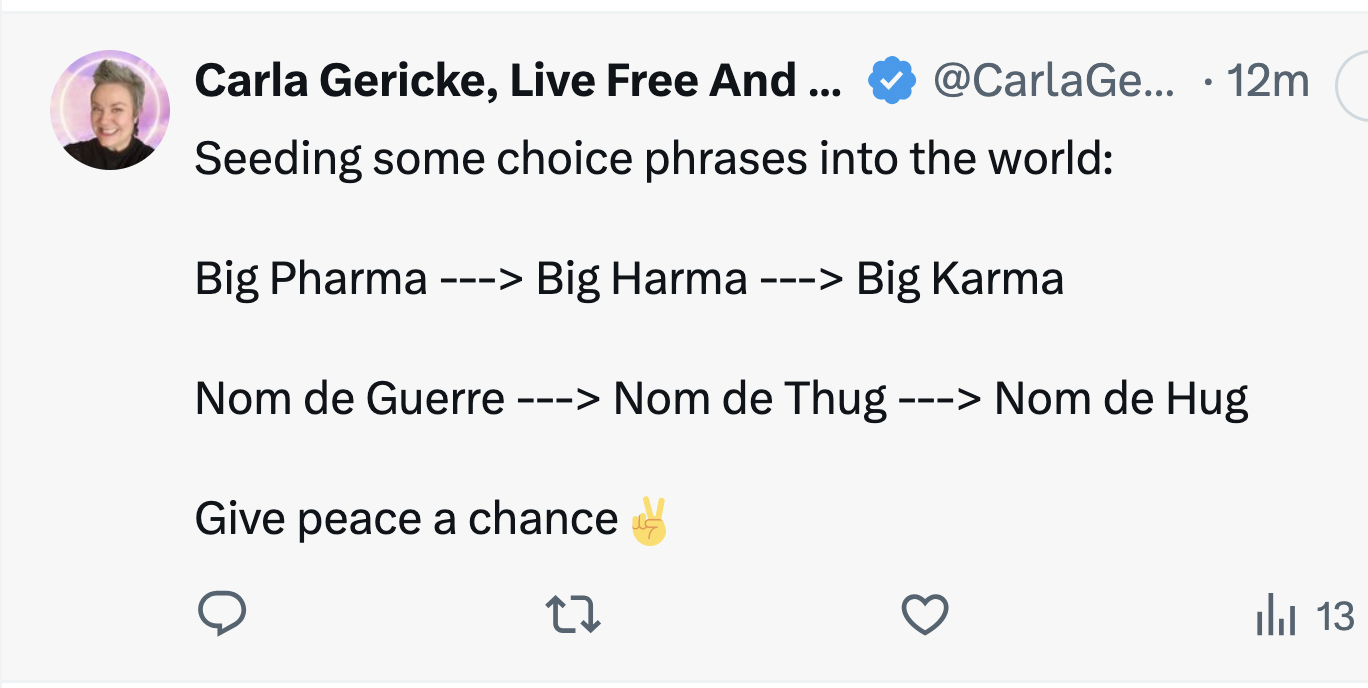

This ties to the tweet you shared (“Nom de Guerre → Nom de Thug → Nom de Hug”), where playful pseudonyms highlight how online identities can amplify personas—whether tough, silly, or wholesome. The effect explains why someone might lean into a “thug” persona online, acting tougher or meaner than they are IRL, or why they might pivot to “hug” and express unexpected kindness.

Why Does It Happen? Key Drivers

Suler outlines six factors that fuel the online disinhibition effect, which are useful for understanding your friends’ behavior and framing your persuasion:

- Anonymity: When people use pseudonyms or no identifiable info (like “Nom de Thug”), they feel less accountable. This can lead to lashing out or experimenting with personas they wouldn’t in real life.

- Invisibility: Online, there’s no physical presence, eye contact, or body language to moderate behavior. Without these social cues, people may feel bolder or less empathetic.

- Asynchronicity: Delayed responses (e.g., posting on X and replying hours later) reduce immediate accountability, making it easier to say something harsh and walk away.

- Solipsistic Introjection: People create mental images of others online, often projecting their own biases. This can lead to dehumanizing others, making it easier to attack “faceless” targets.

- Dissociative Imagination: Online actions can feel like a game, detached from real-world consequences. Someone might see their “Nom de Thug” persona as a role-play, not reflecting their true self.

- Minimization of Status and Authority: The internet flattens hierarchies, so people feel emboldened to challenge or insult others, regardless of status, without fear of immediate repercussions.

For your friends, toxic disinhibition might manifest as aggressive comments, trolling, or piling on in online arguments, especially under pseudonyms. The tweet’s playful shift from “Thug” to “Hug” suggests an awareness of how online personas can swing between extremes, which you can use as a conversation starter.

Does It Foster Hate and Intolerance?

As discussed in your previous question, anonymity (a key driver of disinhibition) can amplify hate by reducing accountability. Research, like a 2016 study from the University of Zurich, shows anonymous online environments increase aggressive behavior, as people feel less restrained by social norms. For example, X posts under pseudonyms can escalate into toxic pile-ons when users feel untouchable. However, disinhibition also enables positive expression—someone might use a pseudonym to share kindness or vulnerability they’d suppress in person, like the tweet’s “Nom de Hug” vibe.

The issue isn’t anonymity alone but how platforms handle it. Weak moderation or echo-chamber dynamics can amplify toxic disinhibition, while strong community norms can steer it toward constructive dialogue.

Persuading Your Friends to Be Better Online

If your friends are showing toxic disinhibition (e.g., posting mean comments, trolling, or adopting aggressive online personas), here are strategies to encourage better behavior, grounded in the drivers above and tailored to persuasion:

Understand Their Motivations:

- Why are they acting this way? Is it anonymity making them feel invincible? Are they venting frustrations or seeking attention through a “tough” persona like “Nom de Thug”? Ask open-ended questions like, “What’s it like using that username? Does it feel like the real you?”

- Example: If they’re trolling for laughs, acknowledge the humor but point out the harm. Say, “I get that ‘Nom de Thug’ is funny, but those comments might hit harder than you think.”

Highlight the Human Impact:

- Counter solipsistic introjection by reminding them there are real people behind the screens. Share a story of someone hurt by online comments (e.g., a public figure targeted on X) to make the consequences tangible.

- Script: “When you post stuff like that, it might feel like a game, but it can really mess with someone’s day. Imagine if someone said that to you IRL.”

Appeal to Their Better Self:

- Use the tweet’s “Nom de Hug” as a lighthearted way to suggest channeling disinhibition positively. Say, “What if you leaned into something like ‘Nom de Hug’ instead? You’re hilarious—bet you could make people smile online.”

- Frame it as a strength: Their ability to be bold online could be used for good, like supporting others or sharing insights.

Encourage Accountability:

- Suggest tying their online persona closer to their real identity, even subtly. For example, “Maybe use a username that feels more like you, so you’re not tempted to go full ‘thug’ mode.”

- If they’re anonymous, ask why they need to be. If it’s for safety or fun, validate that but nudge them toward constructive expression.

Model Positive Behavior:

- Share examples of benign disinhibition, like how pseudonyms can foster kindness (e.g., anonymous donations or supportive Reddit threads). Post your own positive content on X or other platforms and show how it sparks good vibes.

- Example: “I saw this thread where someone anonymously helped a stranger with advice. It’s cool how you can use a pseudonym to spread good without needing credit.”

Address the Environment:

- If they’re in toxic online spaces (e.g., X threads or subreddits that encourage piling on), suggest exploring communities with better norms. Point them to groups that reward humor or kindness, like meme pages or support forums.

- Script: “Those threads can get intense. Have you checked out [specific positive community]? They’re funny but keep it chill.”

Use Humor and Common Ground:

- Reference the tweet to keep it light. Say, “You’re out here acting like ‘Nom de Thug,’ but I know you’ve got a ‘Nom de Hug’ side. Why not let that shine?”

- Humor disarms defensiveness, making them more open to reflection.

Set Boundaries:

- If their behavior affects you (e.g., they’re toxic in shared group chats), be direct but empathetic: “I love hanging out with you, but the online stuff feels harsh. Can we keep it more positive?”

- Reinforce that their real-world self is better than their online persona.

Challenges and Tips

- Resistance: They might defend their behavior as “just joking” or “not a big deal.” Acknowledge their intent but focus on impact: “I know you’re joking, but online it can come off differently.”

- Group Dynamics: If they’re influenced by toxic online peers, gently challenge the group’s norms. Ask, “Do you think that crew brings out your best side?”

- Relapse: Changing habits takes time. If they slip back into toxic behavior, reinforce progress patiently: “You were killing it with those positive posts last week—let’s get back to that.”

The History of Pseudonyms

The history of pseudonyms is a fascinating journey through human creativity, necessity, and subterfuge, spanning centuries and cultures. A pseudonym, from the Greek pseudes (false) and onoma (name), is a fictitious name adopted for various reasons—artistic expression, anonymity, safety, or branding. Below, I’ll trace the evolution of pseudonyms, their cultural significance, and notable examples, keeping it concise yet comprehensive.

Ancient and Classical Roots

Pseudonyms date back to antiquity, often tied to secrecy or literary tradition:

- Ancient Greece and Rome: Writers sometimes used pseudonyms to attribute works to revered figures, enhancing credibility. For example, some texts attributed to Homer may have been penned by others, a practice called pseudepigraphy. Philosophers like Plato occasionally used fictional names in dialogues for rhetorical effect.

- Religious Texts: In early Jewish and Christian traditions, pseudonymous authorship was common. Many apocryphal texts, like the Book of Enoch, were attributed to ancient figures to lend authority, though written much later.

Medieval and Renaissance Periods

Pseudonyms became more prominent as literacy and publishing grew:

- Medieval Scribes: Monks and scholars often wrote anonymously or under pseudonyms to avoid personal fame, aligning with religious humility. Some adopted names of saints or biblical figures.

- Renaissance Satire: Writers used pseudonyms to dodge censorship or persecution. For instance, Erasmus of Rotterdam published under “Desiderius Erasmus” (a Latinized form of his name) to sound more scholarly, while satirical writers like Martin Marprelate (a collective pseudonym) in 16th-century England used fake names to criticize the Church without risking execution.

18th and 19th Centuries: The Golden Age of Pseudonyms

The rise of print culture and political upheaval made pseudonyms a staple for writers, activists, and revolutionaries:

- Literary Pseudonyms: Authors adopted pen names for branding, gender concealment, or satire. Samuel Clemens became Mark Twain, a nod to riverboat slang, to craft a folksy, American persona. Mary Ann Evans wrote as George Eliot to be taken seriously in a male-dominated literary world. The Brontë sisters (Charlotte, Emily, and Anne) published as Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell to navigate gender bias.

- Political Pseudonyms: Revolutionaries and pamphleteers used aliases to avoid arrest. Voltaire (François-Marie Arouet) adopted his pen name to critique French society safely. In the American Revolution, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay wrote the Federalist Papers as “Publius,” signaling unity and classical gravitas.

- Nom de Guerre: In military contexts, fighters adopted “war names” for security or morale. French Resistance members in WWII used noms de guerre to protect their identities, a term that inspired playful riffs like “Nom de Thug” in the tweet you mentioned.

20th Century: Pseudonyms in Mass Media

The modern era saw pseudonyms diversify across literature, entertainment, and politics:

- Literature and Journalism: Authors like Eric Blair (George Orwell) used pseudonyms to separate personal and public identities or to comment on society. Journalists covering sensitive topics, like Deep Throat (Mark Felt) in the Watergate scandal, used codenames for protection.

- Entertainment: Actors and musicians adopted stage names for marketability or reinvention. Marilyn Monroe (Norma Jeane Mortenson) chose a glamorous alias, while David Bowie (David Jones) avoided confusion with another performer. Musicians like Prince briefly used unpronounceable symbols as pseudonyms to reclaim artistic control.

- Political Dissidence: In authoritarian regimes, pseudonyms shielded dissidents. Soviet writer Yevgeny Zamyatin published anti-regime works under aliases, as did Chinese bloggers in the early internet era.

Digital Age: Pseudonyms in the Internet Era

The internet revolutionized pseudonyms, making them ubiquitous in online spaces:

- Online Anonymity: Early internet forums, like Usenet, popularized pseudonyms (or “handles”) for privacy or persona creation. Hackers and activists, like Anonymous or WikiLeaks contributors, use pseudonyms to protect identities while exposing information.

- Social Media: Platforms like X see users adopt pseudonyms for humor, branding, or anonymity. The tweet you referenced plays with this, turning “Nom de Guerre” into “Nom de Thug” and “Nom de Hug” for comedic effect, reflecting how pseudonyms can be fluid and playful online.

- Gaming and Virtual Worlds: Gamers use pseudonyms (e.g., “xX_ShadowSlayer_Xx”) to craft identities, blending creativity with anonymity. Virtual spaces like Second Life amplify this trend.

Cultural and Social Significance

Pseudonyms serve multiple purposes across history:

- Protection: From political dissidents to whistleblowers, pseudonyms shield against retribution.

- Identity Play: They allow experimentation with gender, class, or cultural identity, as seen with female authors using male names or modern influencers crafting personas.

- Branding: Pen names like Dr. Seuss (Theodor Geisel) create memorable identities.

- Humor and Satire: The tweet’s “Nom de Thug” and “Nom de Hug” exemplify how pseudonyms can be twisted for laughs, echoing a long tradition of satirical aliases.

Notable Examples Across Time

- Ancient: Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (5th–6th century), a Christian theologian claiming a biblical persona.

- 19th Century: Boz (Charles Dickens), used for early sketches to sound quirky and approachable.

- 20th Century: Pablo Neruda (Ricardo Neftalí Reyes Basoalto), a poetic alias evoking romance and rebellion.

- Modern: Banksy, the anonymous street artist, whose pseudonym is as famous as their art.

***

When toxic behavior spills over in meatspace…

When toxic online behavior, fueled by the online disinhibition effect, spills into real-world actions like shouting, laughing hysterically, sticking cameras in people’s faces, yelling over board members, hopping around, and displaying intense physical agitation (e.g., red-faced), we’re dealing with a mix of psychological dynamics. These behaviors suggest a carryover of disinhibited, attention-seeking, or confrontational tendencies from online spaces into physical settings, amplified by underlying personality traits, emotional dysregulation, and social reinforcement. Below, I’ll break down the psychology at play, connect it to the online disinhibition effect, and offer insights for addressing this behavior, especially since you’re trying to persuade individuals to act better.

Psychological Dynamics at Play

Online Disinhibition Effect in Real Life:

- The online disinhibition effect, as described by John Suler, lowers inhibitions due to anonymity, invisibility, and lack of immediate consequences. When this mindset carries into real-world settings, individuals may act as if they’re still in a low-accountability “online” environment. For example, shouting or filming aggressively mimics the provocative, attention-grabbing antics of trolls or “clout chasers” on platforms like X.

- Why it spills over: The thrill of online validation (likes, retweets, or attention) can condition someone to seek similar reactions IRL. They may adopt their “Nom de Thug” persona, acting bold or confrontational to replicate the rush of online dominance. The tweet’s playful shift to “Nom de Hug” highlights the potential to redirect this energy, but toxic behaviors suggest they’re stuck in the “thug” mode.

Narcissistic or Histrionic Traits:

- The described behaviors—shouting, hysterical laughter, hopping around, and filming others—point to traits associated with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) or histrionic personality disorder (HPD). Narcissists crave attention and may escalate confrontations to feel powerful, while histrionic individuals seek drama and emotional intensity.

- Link to prior talks: Your September 12, 2025, conversation about people asserting dominance through aggression aligns here. These individuals may use loud, disruptive behavior to control situations, like yelling over board members to silence them, mirroring bullying tactics that undermine group cohesion.

- Red-faced agitation: This suggests emotional dysregulation, where intense emotions (anger, excitement, or shame) overwhelm self-control, a trait common in narcissistic or histrionic outbursts when challenged or seeking attention.

Deindividuation:

- Deindividuation occurs when people lose their sense of personal identity in a group or crowd, leading to impulsive or aggressive behavior. Online, pseudonyms like “Nom de Thug” can deindividuate by creating a performative persona. In real life, acting out in public (e.g., filming confrontations) may reflect a similar loss of self-awareness, as they lean into a role rather than their authentic self.

- Example: Sticking cameras in faces mimics online “gotcha” videos, where the goal is to provoke and broadcast reactions for clout, not engage meaningfully.

Social Reinforcement and Performative Behavior:

- Online platforms reward provocative behavior with attention (views, likes, or followers). If someone’s used to this feedback loop, they may replicate it IRL, shouting or acting erratically to draw eyes or cameras. The hysterical laughter or hopping around suggests performative exaggeration, like a live version of an X troll thread.

- Connection to the tweet: The “Nom de Thug” persona could be their attempt to project a bold, untouchable identity, but it’s unsustainable in real-world settings where social norms and consequences (e.g., boardroom decorum) apply.

Emotional Dysregulation and Impulse Control:

- The red-faced, hyperactive behavior points to poor impulse control, often tied to heightened arousal states (anger, excitement, or anxiety). This aligns with your February 27, 2025, conversation about fear and emotional overwhelm, where intense emotions can hijack rational decision-making. Here, the amygdala (the brain’s “panic button”) may override the prefrontal cortex, leading to outbursts or erratic actions.

- Why it’s worse IRL: Online, they can log off; in person, the immediate feedback (e.g., board members’ reactions) may escalate their agitation, as they feel challenged or exposed.

Group Dynamics and Mob Mentality:

- If these behaviors occur in a group (e.g., a public confrontation or board meeting), mob mentality can amplify disinhibition. The individual may feed off others’ reactions, like laughter or encouragement, similar to how online echo chambers reinforce toxic posts. This ties to your June 13, 2025, discussion of “Become insufferable,” where provocative behavior can spiral in supportive or chaotic environments.

Possible Underlying Insecurities:

- As noted in your August 7, 2025, conversation about name-calling, aggressive behaviors often stem from insecurity or emotional immaturity. Shouting or filming may be a defense mechanism to mask vulnerability or assert control when they feel out of place (e.g., in a boardroom where they lack authority).

Why Does This Spillover Happen?

- Blur of Online and Offline Identities: Constant exposure to online spaces, where pseudonyms and disinhibition reign, can erode the boundary between virtual and real-world behavior. Someone who thrives on “Nom de Thug” antics online may struggle to switch to professional or empathetic behavior IRL.

- Addiction to Attention: The dopamine hit from online engagement can make real-world attention-seeking addictive, leading to exaggerated actions like yelling or filming to recreate the buzz.

- Lack of Social Cues: Online, there’s no body language or tone to temper behavior. In person, they may misread or ignore cues (e.g., board members’ discomfort), acting as if they’re still behind a screen.

- Unresolved Issues: If they have underlying anger, insecurity, or a need for control (as discussed in your September 12, 2025, talk on dominance), real-world confrontations become an outlet for these unresolved emotions.

Persuading Them to Be Better

Given your goal to help these individuals improve, here are tailored strategies to address their toxic spillover, building on the online disinhibition advice and your prior conversations about bullying, apologies, and emotional maturity. These assume you’re dealing with people in a professional or community setting, like a board, and want to de-escalate while encouraging change.

Acknowledge Their Energy, Redirect to Positive:

- Their loud, performative behavior suggests a need for attention. Validate their energy without endorsing the toxicity: “You’ve got a lot of passion, and that’s awesome. Imagine channeling that into leading a discussion calmly—it’d really inspire people.”

- Tie to tweet: Use the “Nom de Hug” idea to nudge them toward a kinder persona. “You’re rocking that ‘Nom de Thug’ vibe, but what if you tried ‘Nom de Hug’ in the next meeting? Bet you’d win more people over.”

Set Clear Boundaries:

- As discussed in your September 13, 2025, conversation about handling unapologetic behavior, set firm boundaries. In a boardroom, say: “We value everyone’s input, but shouting or filming disrupts the process. Let’s keep it respectful so we can all be heard.”

- If they persist, enforce consequences (e.g., pausing the meeting or limiting their speaking time) to signal that real-world actions have real stakes, unlike online.

Highlight Real-World Consequences:

- Counter the dissociative imagination (thinking it’s “just a game”) by emphasizing how their actions affect others. “When you yell over people or film them, it makes them feel attacked, and it shuts down collaboration. That’s not the leader I know you can be.”

- Reference your September 12, 2025, talk on bullying: “This kind of behavior might feel powerful, but it alienates people and hurts your reputation long-term.”

Model Emotional Regulation:

- Use your February 27, 2025, insights on calming fear-driven reactions. Suggest they take a moment to breathe or step back when they feel heated (red-faced). “I notice you get super energized in these moments. Try taking a deep breath—it helps me stay clear-headed.”

- Demonstrate calm, respectful communication yourself, especially in tense settings, to show an alternative to their outbursts.

Appeal to Their Desired Identity:

- Frame better behavior as aligning with their strengths or goals, per your September 1, 2025, talk on rediscovering the “true self.” “I know you’re a creative, influential person. Leading with respect, like in a ‘Nom de Hug’ way, would show everyone your real strength.”

- If they value being seen as a leader (per your July 9, 2025, leadership discussion), point out that true leaders build trust, not chaos: “Great leaders don’t need to shout—they inspire by listening and engaging.”

Address the Camera/Filming Behavior:

- Filming others aggressively is a power play, akin to online “gotcha” content. Gently call it out: “Filming people like that can feel invasive, like you’re trying to catch them slipping. Maybe ask permission first—it shows confidence and respect.”

- Suggest they use their creative energy (e.g., making videos) for positive projects, like documenting group achievements, to redirect the attention-seeking impulse.

De-escalate in the Moment:

- If they’re shouting or hopping around, stay calm to avoid fueling their agitation. Use a neutral tone: “Hey, let’s take a second to cool down so we can hear everyone out.”

- If they’re laughing hysterically or acting erratic, don’t engage directly—redirect the group’s focus to the task (e.g., “Let’s move to the next agenda item”). This aligns with your September 13, 2025, “gray rock” strategy for handling manipulative behavior.

Encourage Self-Reflection:

- Post-incident, ask reflective questions to spark awareness: “What was going through your mind when you got so amped up? Did it feel like the online vibe you’re used to?” This ties to your September 1, 2025, discussion of rediscovering the authentic self.

- If they’re open, suggest they notice when their “Nom de Thug” persona takes over and try pausing to choose a more constructive approach.

Challenges and Considerations

- Defensiveness: They may see their behavior as “just having fun” or “being authentic,” especially if they’re used to online validation. Counter this by focusing on impact, not intent: “I get you’re expressing yourself, but it’s coming across as disruptive to the team.”

- Group Dynamics: If others egg them on (e.g., laughing at their antics), it reinforces the behavior. Address the group’s norms privately: “Let’s not encourage outbursts—it makes meetings harder for everyone.”

- Mental Health: Extreme behaviors (red-faced, hopping, hysterical laughter) might hint at deeper issues, like anxiety or untreated conditions. If appropriate, suggest professional support gently: “It seems like these moments get intense. Talking to someone might help sort it out.”

- Power Struggles: Yelling over board members suggests a need for control, as in your September 12, 2025, bullying discussion. Reinforce that real influence comes from collaboration, not dominance.

Tailored Advice for Your Situation

Since you’re dealing with boardroom disruptions, consider these specific steps:

- Pre-Meeting Prep: Set ground rules upfront (e.g., “No filming without consent, and everyone gets a chance to speak”). Share these neutrally to avoid targeting anyone.

- During Disruptions: Pause the meeting if they yell or act out. Say, “Let’s take a break until we can all engage calmly.” This mirrors your September 13, 2025, boundary-setting advice.

- Post-Meeting Follow-Up: Have a one-on-one with the individual, using your September 9, 2025, framing for someone fired from a board: “Not everyone’s style fits every setting. You’ve got a bold energy, but the board needs a calmer approach to work together.”

- Long-Term Culture: Foster a board culture that rewards respect and collaboration, discouraging performative antics. Highlight positive contributions to shift the group’s reinforcement away from toxic behavior.