Unalienable… what does this mean, and how has it been subverted

Meaning of “Unalienable”

“Unalienable” (also spelled “inalienable” in modern usage) refers to rights that are inherent to human beings, cannot be surrendered, transferred, taken away, or denied by any government or authority. These are often described as natural rights or God-given rights, existing by virtue of being human rather than granted by laws or rulers.

The term is most famously used in the U.S. Declaration of Independence (1776):

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Here, “unalienable” emphasizes that these rights are not alienable (i.e., they cannot be separated from the individual). “Unalienable” and “inalienable” are synonyms with no meaningful difference today—”unalienable” was the preferred 18th-century spelling in the Declaration’s final version, while “inalienable” became dominant later.

The concept draws from Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke, who argued for natural rights to life, liberty, and property (Jefferson adapted this to “pursuit of Happiness”). Governments exist to secure these rights, deriving power from the consent of the governed; if they fail, people have the right to alter or abolish them.

How the Concept Has Been “Subverted” or Infringed

The idea of unalienable rights has faced criticism and real-world violations throughout history, often described as “subversion” when governments or societies undermine their universality or inviolability:

- Historical Hypocrisy and Exclusion in America:

- The Declaration proclaimed these rights while slavery remained legal, denying them to enslaved Africans and their descendants. Indigenous peoples faced displacement and genocide, and women were excluded from full rights.

- This contradiction highlighted that “all men” was interpreted narrowly (white, property-owning males), subverting the universal claim. Abolitionists, civil rights leaders (e.g., Martin Luther King Jr.), and suffragists later invoked the Declaration to expand protections via amendments and laws.

- Philosophical Criticism:

- Utilitarian Jeremy Bentham called natural rights “nonsense upon stilts,” arguing rights are created by law, not inherent.

- Some modern critics (e.g., cultural relativists) question universality, claiming rights vary by culture or that without enforcement (e.g., government), they don’t exist in practice.

- Others argue rights can conflict (e.g., one person’s liberty infringing another’s safety), requiring regulation.

- Government Infringements:

- Rights are often violated despite being “unalienable”—e.g., internment of Japanese Americans during WWII, restrictions during emergencies, or debates over gun rights vs. public safety.

- Some conservatives argue modern expansions (e.g., positive rights like healthcare) subvert the original focus on negative rights (freedom from interference).

- In broader human rights discourse, efforts to prioritize certain rights (e.g., traditional vs. newer social rights) have sparked debates about diluting core unalienable ones.

In essence, while the concept asserts absolute inviolability, history shows frequent subversion through exclusion, violation, or redefinition—yet it remains a powerful ideal driving reforms toward greater inclusion and protection.

break down in columns what are positive rights and negative rights, and who pays

Positive Rights vs. Negative Rights

The distinction between negative rights (also called liberty rights) and positive rights (also called entitlement or welfare rights) is a key concept in political philosophy, popularized by Isaiah Berlin in his essay “Two Concepts of Liberty” (1958). Negative rights focus on freedom from interference, while positive rights focus on freedom to have or achieve something, often requiring active provision.

Here’s a breakdown in columns:

| Aspect | Negative Rights | Positive Rights |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Rights that require others (individuals or government) to refrain from interfering or acting against you. They protect liberty by imposing duties of non-interference. | Rights that require others (usually government) to actively provide goods, services, or opportunities. They impose duties to act or provide. |

| Philosophical Basis | Classical liberalism (e.g., John Locke, U.S. Founding Fathers’ emphasis on natural rights). Associated with “negative liberty” (freedom from coercion). | Modern welfare states and social democracy. Associated with “positive liberty” (freedom to fulfill potential). Often linked to second-generation human rights (economic/social). |

| Examples | – Freedom of speech (others must not censor you) – Right to life/liberty (protection from murder, enslavement, or arbitrary arrest) – Private property (others must not steal or seize it) – Freedom of religion (no forced belief) | – Right to education (government provides schools/teachers) – Right to healthcare (government-funded treatment) – Right to social security/welfare (benefits during unemployment) – Right to housing or minimum standard of living |

| Cost/Who Pays | Generally low direct cost: Enforced through restraint (no action needed beyond basic legal systems). Any enforcement (e.g., courts, police to prevent violations) is funded by taxpayers collectively, but the right itself doesn’t require transferring resources to individuals. Critics argue pure negative rights have minimal burden. | High direct cost: Requires resources, labor, and funding to provide the good/service. Typically paid by taxpayers (through government redistribution via taxes). Can involve coercion (forced contribution) and may conflict due to scarcity (not everyone can receive equally). |

| Criticisms/Debates | Seen as universally compatible (everyone can enjoy them simultaneously without conflict). Enforcement still needs some positive action (e.g., police protection). | Often criticized as creating dependency or infringing negative rights (e.g., taxing property to fund welfare). Some argue they aren’t “true” rights since they depend on others’ labor/effort. Proponents say they’re essential for equality and dignity. |

This distinction ties into discussions of unalienable rights (mostly negative in the classical sense) and the UDHR (which includes both, e.g., Articles 3–21 lean negative; 22–27 positive).

Note: Some philosophers argue the divide isn’t absolute—enforcing negative rights also requires positive actions (e.g., funding courts). However, the core difference in burden and obligation remains widely recognized.

would it be fair to say negative rights are based on individual action/freedom and positive rights are a form of communism (making people do something for you)

Assessing the Characterization of Negative and Positive Rights

Your question touches on a common debate in political philosophy, where negative rights are often framed as protections for individual autonomy, while positive rights involve obligations on others (typically society or government) to provide resources or services. I’ll break this down step by step to evaluate if your description is “fair,” drawing on standard definitions and critiques. Overall, the first part of your statement aligns reasonably well with classical liberal views, but the second part oversimplifies and isn’t entirely accurate—positive rights aren’t inherently “communist,” though they can involve elements of compulsion that critics associate with collectivist systems.

1. Negative Rights as Based on Individual Action/Freedom

- Is this fair? Yes, this is a fair characterization in many philosophical traditions.

- Explanation: Negative rights (also called “liberty rights” or “negative liberties”) are fundamentally about non-interference—they require others to refrain from actions that would hinder your freedom. This emphasizes individual agency: you are free to act as you choose, as long as you don’t infringe on others’ similar freedoms. For instance:

- The right to free speech means no one (especially government) can censor you, allowing you to express yourself independently.

- The right to property means others can’t seize your belongings, enabling you to use or trade them as you see fit.

- This aligns with thinkers like John Locke and Isaiah Berlin, who saw negative rights as the foundation of personal liberty, where freedom is the absence of external constraints. They are “self-executing” in the sense that they don’t demand active provision from others; enforcement mainly involves preventing violations (e.g., via courts or police).

- Caveat: Even negative rights aren’t purely “individual” in practice—they often require societal structures (like a legal system) to protect them, which involves some collective action.

2. Positive Rights as a Form of Communism (Making People Do Something for You)

- Is this fair? Not really—this is an oversimplification and a bit loaded. While positive rights do involve obligations on others (which can feel like “making people do something”), equating them directly with communism ignores their presence in non-communist systems and reduces a broad concept to a pejorative label.

- Explanation: Positive rights (also called “welfare rights” or “positive liberties”) entitle individuals to receive certain goods, services, or opportunities, which often requires active intervention from society or government. This can involve “making people do something” in the form of redistribution (e.g., taxes funding public services), which critics describe as coercive because it compels contributions from others. Examples include:

- The right to education: Governments must provide schools, teachers, and funding, paid for by taxpayers.

- The right to healthcare: This might require doctors, hospitals, or subsidies, again funded collectively.

- Link to Communism? Positive rights are prominent in communist ideologies (e.g., Marxist theory emphasizes economic rights like the right to work or housing, provided by the state in a classless society). Communist constitutions often promised extensive positive rights, but critics argue they failed due to overpromising without sustainable delivery. However:

- Positive rights aren’t exclusive to communism—they exist in capitalist democracies too. For example, the U.S. has positive rights elements like public education, Social Security, and unemployment benefits. European social democracies (e.g., Sweden, Canada) blend them with market economies through welfare states.

- The “communism” label often comes from libertarian or conservative critiques, who see positive rights as a slippery slope toward collectivism because they prioritize equality over pure individual freedom. But communism specifically involves abolishing private property and class structures, which goes far beyond just providing rights like healthcare.

- Instead of “communism,” a more neutral view is that positive rights reflect social contract ideas (e.g., from Rousseau or modern welfare theorists), where society agrees to mutual support for the common good. The coercion aspect (taxes) is debated: proponents say it’s justified for equity and human dignity, while opponents argue it violates negative rights (e.g., property rights).

Key Differences and Overlaps in a Table

To clarify, here’s a quick comparison highlighting why the communism link isn’t straightforward:

| Aspect | Negative Rights (Individual Freedom Focus) | Positive Rights (Obligation/Provision Focus) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Restrains actions (e.g., “don’t interfere”) | Requires actions (e.g., “provide this”) |

| Basis in Freedom | Freedom from coercion or harm | Freedom to achieve or access something |

| Association with Ideologies | Classical liberalism, libertarianism (e.g., U.S. Bill of Rights emphasizes these) | Social democracy, socialism; communism amplifies them but they’re not unique to it |

| “Making People Do Something” | Minimal—mostly passive restraint | Yes, via taxes/redistribution; seen as coercive by critics, but voluntary in social contracts |

| Examples in Non-Communist Systems | Freedom of assembly (universal in democracies) | Universal basic education (in most capitalist countries) |

In summary, your first point captures the essence of negative rights well, but labeling positive rights as “communism” isn’t fair because it ignores their role in diverse political systems. The debate often boils down to balancing individual liberty with collective welfare—positive rights can enable freedom (e.g., education empowers individual action), but they do introduce elements of compulsion that some view as antithetical to pure individualism. If you’re drawing from a specific thinker or context, feel free to provide more details for a deeper dive!

“aren’t inherently “communist,” though they can involve elements of compulsion” which positive rights do NOT involve compulsion?

Do Any Positive Rights Avoid Compulsion Entirely?

To directly address your question: In the standard philosophical distinction (particularly from libertarian and classical liberal perspectives), no typical positive right avoids elements of compulsion when enforced at a societal or governmental level. Positive rights inherently require active provision of goods, services, or opportunities by others—often funded through taxation or regulated redistribution—which critics argue involves coercion (forcing people to contribute resources or labor against their will).

However, there are nuances and edge cases where philosophers argue positive rights can be framed or implemented without direct compulsion:

1. Purely Voluntary or Contractual Positive Rights

- These aren’t “universal” human rights but arise from mutual agreement.

- Example: If you voluntarily join a private club, cooperative, or insurance pool, you gain a “positive right” to benefits (e.g., mutual aid, shared resources) provided by members. No one is forced—participation is consensual, and you can leave.

- This aligns with contract-based obligations: You trade some freedom for provision, but it’s not coerced by the state.

- Limitation: These aren’t inherent or unalienable; they’re optional and don’t apply universally.

2. Rephrased as Negative Rights (Philosophical Workaround)

- Some thinkers (e.g., James Sterba) argue that certain positive claims can be reformulated as negative rights to avoid forced labor or taxation.

- Example: Instead of a “positive right to welfare” (government must provide food/housing via taxes), rephrase as a “negative right not to be prevented from taking surplus resources” from the wealthy if you’re in dire need. This shifts the burden: The poor can take what’s unused, without forcing others to actively give.

- This avoids compelling providers but still involves potential conflict (e.g., self-help enforcement) and isn’t widely accepted as a true positive right.

3. Hybrid or Borderline Cases Often Debated as Positive

- Rights like fair trial (UDHR Article 10) or legal counsel in criminal cases require the state to provide lawyers/judges, funded by taxes—compulsion involved.

- Protection from private violence (e.g., police response) is sometimes called positive but often seen as enforcing negative rights (to life/security).

- No clear example escapes compulsion in practice for universal enforcement.

Why Most Views Say All Enforced Positive Rights Involve Compulsion

| Critique Perspective | Reason Positive Rights Require Compulsion | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Libertarian/Classical Liberal | Provision demands resources/labor from others; taxation = coerced transfer, violating negative property rights. | Healthcare, education, welfare—can’t be guaranteed universally without forcing contributions. |

| General Philosophical Consensus | Positive rights impose “positive duties” (to act/provide), while negative rights impose only “negative duties” (to refrain). Scarcity means someone pays involuntarily. | Social security, housing—voluntary charity isn’t a “right” since it can be withheld. |

| Practical Enforcement | Even “non-coercive” ideals (e.g., voluntary funding) fail at scale; states rely on compulsory taxes/laws. | No modern welfare state funds positive rights purely voluntarily. |

In summary, while positive rights can exist without compulsion in narrow, voluntary contexts (e.g., private contracts or mutual aid societies), universal or state-enforced ones—like those in the UDHR (education, work, social security)—almost always involve some coercion through taxation or regulation. This is why critics (e.g., from libertarian traditions) argue positive rights inherently conflict with pure individual freedom. Proponents counter that such “compulsion” is justified via social contract or democracy for greater equity. If you’re thinking of a specific right, I can analyze it further!

“social contract”… under strict contract law, how does one who has not signed nor explicitly agreed to a contract held to its terms?

Strict Contract Law: Binding Without Signature or Explicit Agreement

Under modern contract law (e.g., in common law jurisdictions like the US, UK, or influenced systems), a person can be bound to a contract without signing it or explicitly agreeing (e.g., saying “I agree”). This occurs primarily through:

- Implied-in-fact contracts: These arise from the parties’ conduct and circumstances showing mutual intent to be bound. For example:

- Ordering and eating food at a restaurant implies agreement to pay the listed price.

- Continuing to work for an employer and accepting pay implies acceptance of employment terms.

- Performing services or delivering goods after receiving an offer, without objection.

- Actions substituting for signature: Beginning performance, accepting benefits, or failing to object (when reasonable to expect objection) can demonstrate acceptance.

- Promissory estoppel: If one party reasonably relies on a promise (causing detriment), the promisor may be bound even without full mutual agreement.

However, key requirements must be met: offer, acceptance (via conduct), consideration (exchange of value), and intent to be legally bound. Silence alone rarely binds unless prior dealings or context imply it. Contracts for major items (e.g., real estate) often require writing/signatures under the Statute of Frauds.

In short: Yes, you can be bound without explicit agreement if your behavior objectively shows consent.

The “Social Contract” Analogy and Why It’s Not a Strict Legal Contract

The social contract in political philosophy (Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Rawls) is a metaphor or thought experiment explaining why we have political obligation (duty to obey laws) and government legitimacy. It is not a literal contract under law.

- No actual agreement: No one signs or explicitly consents (except immigrants via naturalization oaths). Most are born into it.

- Tacit/implied/hypothetical consent:

- Locke: Tacit consent via residing in territory, using roads, or inheriting property—implying you accept benefits and thus obligations.

- Rousseau: More collective “general will.”

- Modern versions (e.g., Rawls): Hypothetical—what rational people would agree to behind a “veil of ignorance.”

Critics (e.g., David Hume, modern philosophers) argue this fails as a true contract analogy:

| Aspect | Strict Contract Law | Social Contract Theory | Key Criticism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consent Required | Mutual, objective intent (express or implied by conduct) | Tacit (residence/benefits) or hypothetical | No real choice—leaving country is costly/impractical (Hume: like being born on a ship and forced to stay) |

| Opt-Out Possible | Can reject offer or breach (with consequences) | Emigration, but often unrealistic | No reasonable exit; benefits (e.g., roads) hard to avoid without consent |

| Mutual Benefits | Consideration required | Protection, order in exchange for obedience | Unequal; government can breach (unjust laws) without easy remedy |

| Enforceability | Courts enforce if elements met | State enforces via coercion | Not voluntary; more imposition than agreement |

| Historical Basis | Actual past dealings | Fictional/hypothetical origin | “Isn’t worth the paper it’s not written on” (common quip) |

The analogy breaks because:

- Real implied contracts require reasonable opportunity to reject and clear actions showing intent.

- Social “consent” is inescapable for most (born subjects), lacking true voluntariness.

- Philosophers use it normatively (to justify limited government or rights) rather than descriptively (as historical fact).

Many conclude the social contract is not legitimate under strict contract principles—it’s a useful fiction or ideal, but political obligation may rest on other grounds (e.g., fairness, gratitude, natural duty, or democracy). Critics like philosophical anarchists argue no general duty to obey exists without actual consent.

In essence: Under law, non-explicit binding is possible but limited and voluntary. The social contract stretches “consent” far beyond that, making the analogy weak or illusory to skeptics.

strictly speaking, what would one call a system under which you are born and are subject to conditions you did not agree to and that you do not consent to?

Strictly speaking, a political or social system in which individuals are born into obligations, laws, and conditions without their personal consent (explicit or otherwise) is most accurately described as one based on political subjection or non-consensual authority.

Common precise terms used in political philosophy and jurisprudence for such a system include:

| Term | Definition/Usage | Key Proponents/Critics | Why It Fits the Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjection | Being placed under the authority or dominion of a ruler/state without voluntary agreement. | Hobbes (in state of nature vs. civil society); modern critics of state legitimacy. | Emphasizes involuntary submission from birth. |

| Coercive Authority | Authority enforced by threat of force, without requiring individual consent. | Weber (monopoly on legitimate violence); libertarian theorists. | Laws apply regardless of agreement; non-compliance punished. |

| Philosophical Anarchism | The view that no existing state has legitimate authority because it lacks genuine consent from subjects. | Robert Paul Wolff (In Defense of Anarchism); A. John Simmons. | Argues all states impose non-consensual rule on those born within borders. |

| Involuntary Governance | Rule over persons who have not voluntarily submitted to it. | Lysander Spooner (No Treason); modern voluntarists. | Explicitly rejects tacit consent theories. |

| De Facto Authority | Authority that exists in practice (backed by power) but lacks moral legitimacy due to absence of consent. | Hume; Raz (on authority). | Distinguishes raw power from justified rule. |

Why Common Alternatives Are Less Precise

- Slavery: Too strong and inaccurate for most modern states—slavery involves ownership of persons and denial of basic rights; most states allow exit (emigration) and some participation (voting).

- Tyranny/Despotism: Implies arbitrary or oppressive rule, but the core issue here is lack of consent, not necessarily cruelty.

- Authoritarianism/Dictatorship: Focuses on concentration of power or lack of democracy, not the fundamental absence of personal consent.

- Feudalism/Serfdom: Historical systems of involuntary allegiance from birth, but outdated for describing modern states.

The Core Philosophical Conclusion

From a strictly consent-based perspective (especially libertarian or voluntarist), any system that imposes binding obligations on individuals from birth—without their actual, explicit, and ongoing consent—is a form of non-voluntary subjection. Critics like Spooner and Wolff argue it cannot be legitimately called a “contract” or “consensual” arrangement at all, regardless of theories of tacit or hypothetical consent.

In short: non-consensual political subjection or involuntary subjection to authority is the most accurate, neutral description. Those who reject the legitimacy of such systems entirely often label it simply as illegitimate state authority.

If something is non-consensual or involuntary… what does that mean?

Definitions of “Non-Consensual” and “Involuntary”

These terms are closely related but have distinct nuances depending on context (e.g., ethics, law, philosophy, or everyday language). Both describe situations lacking genuine, freely given agreement or choice.

| Term | Core Meaning | Key Characteristics | Common Contexts & Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Consensual | An action, relationship, or imposition that occurs without the valid consent of the affected person(s). Consent must be informed, voluntary, ongoing, and uncoerced. | – Emphasizes the absence of agreement. – Consent can be withheld or revoked. – Often implies one party initiates without permission. | – Sexual activity without agreement (sexual assault). – Medical procedures performed without informed consent. – Contracts or terms accepted under duress. |

| Involuntary | Something done against one’s will or without voluntary choice, often due to external force, necessity, or lack of viable alternatives. | – Focuses on lack of free will or choice. – Can include coercion, compulsion, or unavoidable circumstances. – Broader than consent—applies even where “agreement” isn’t relevant. | – Involuntary servitude (forced labor). – Reflex actions (e.g., knee-jerk). – Being drafted into military service against personal desire. – Subjection to laws in a territory where exit isn’t realistically possible. |

Key Overlaps and Differences

- Overlap: Both imply a violation of personal autonomy. Something non-consensual is almost always involuntary, and many involuntary actions are non-consensual.

- Differences:

- Non-consensual specifically references the consent framework (common in interpersonal ethics, law, and rights discussions).

- Involuntary is broader and can apply to non-agent actions (e.g., involuntary muscle spasms) or systemic impositions (e.g., taxes or laws one never agreed to).

- Degrees: Actions can be partially involuntary (limited choices) or fully non-consensual (explicit refusal ignored).

Philosophical and Legal Implications

- In ethics/libertarian thought: Non-consensual or involuntary impositions on persons (e.g., aggression, coercion, or unagreed obligations) are often seen as morally illegitimate unless justified by prior wrongdoing or true necessity.

- In law: Non-consensual acts can be crimes (e.g., assault) or void contracts; involuntary confessions are inadmissible.

- In political philosophy (tying to prior discussion): Systems imposing binding obligations from birth—without actual personal consent—are described as non-consensual subjection or involuntary governance, lacking the voluntariness required for legitimate authority in consent-based theories.

In essence: “Non-consensual” means “without permission or agreement,” while “involuntary” means “not by free choice”—both point to a fundamental denial of individual autonomy.

doesn’t the entire US political system hinge on the “consent of the governed”… if we don’t “consent”… what now?

Yes, the entire founding ideology of the United States explicitly hinges on the principle of “consent of the governed”.

This is stated most clearly in the Declaration of Independence (1776):

“Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

The implication is profound: If a government no longer has the consent of the governed, it loses its legitimacy, and the people have a right “to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government.”

What Forms of “Consent” Does the System Recognize?

In practice, the U.S. political system treats consent as ongoing and collective rather than individual and explicit. The main mechanisms are:

| Mechanism | How It Represents “Consent” | Criticisms (Lack of True Consent) |

|---|---|---|

| Voting / Elections | Periodic elections allow citizens to choose representatives or approve/reject policies. | Low turnout, gerrymandering, two-party dominance, and “none of the above” not being an option mean many feel unrepresented. |

| Residence & Participation | Living in the U.S., using public services (roads, courts, protection), and not emigrating implies tacit consent (Lockean view adopted by many courts). | Born into it—no realistic opt-out; emigration is costly and rare. |

| Constitutional Ratification | The Constitution was ratified by conventions in 1787–1788; later generations are bound by it. | No living person participated; amendments require supermajorities, making change difficult. |

| Jury Duty, Taxes, Obedience | Compliance with laws is interpreted as consent. | Non-compliance leads to coercion (fines, imprisonment), undermining voluntariness. |

From a strict individual-consent perspective (e.g., philosophical anarchism or voluntarism), none of these constitute genuine, personal, revocable consent—especially for those born into the system.

If We (Individually or Collectively) Do Not Consent—What Now?

The tradition and theory provide a spectrum of answers:

- Individual Level: Limited Practical Options

- Emigrate: Legally leave and renounce citizenship (possible but expensive, disruptive, and few countries offer easy entry).

- Civil Disobedience: Non-violent refusal to comply with unjust laws (Thoreau, MLK). Risks punishment but asserts moral withdrawal of consent.

- Internal Exile / Off-Grid Living: Minimize interaction with the state (e.g., homesteading), though still subject to core laws (property taxes, etc.).

- Philosophical Rejection: Many simply withhold moral consent while complying outwardly to avoid coercion. This is common among libertarians and anarchists.

- Collective Level: Constitutional or Revolutionary Paths

- The Founders’ Answer (Declaration of Independence): When government becomes destructive of life, liberty, and happiness, it is the right—nay, the duty—of the people to alter or abolish it.

- Peaceful alteration: Constitutional amendments, conventions, or secession (debated legality post-Civil War).

- Abolition/revolution: Last resort, justified only after “a long train of abuses.”

- Modern Constitutional Mechanisms:

- Article V: Amendment process or a convention of states.

- Elections and political movements to radically reform or decentralize power.

- Secession: Historically attempted (1861); today considered unconstitutional under Supreme Court precedent (Texas v. White, 1869), but some state movements (e.g., Texas, California) periodically revive the idea.

- Realist View

- In practice, the system maintains authority through de facto power (police, courts, military) regardless of philosophical consent. Withdrawal of mass consent could lead to crisis or change, but isolated individual non-consent changes little.

Bottom Line

The U.S. system claims legitimacy from “consent of the governed,” but that consent is largely presumed, collective, and tacit—not individual and explicit. If enough people actively withhold consent and act on it (through voting, movements, or rarer means), change is possible. For the individual who feels no consent was ever given, the honest options are limited: comply under protest, minimize engagement, emigrate, or join collective efforts to alter the system.

The Declaration itself acknowledges that people tolerate a lot before acting: “mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.” The question of “what now?” ultimately returns to each person’s judgment of how “sufferable” the current situation is.

Measure the efforts of the Free State Project as a bulwark against subjugation

Measuring the Free State Project (FSP) as a Bulwark Against Subjugation

The Free State Project, launched in 2001, aims to concentrate liberty-minded individuals (libertarians, classical liberals, voluntarists) in one low-population state to influence policy toward maximal individual freedom and minimal government—directly addressing non-consensual political subjection by creating a jurisdiction with stronger protections for negative rights (e.g., gun ownership, property, speech) and resistance to federal overreach.

New Hampshire was selected in 2003 for its “Live Free or Die” ethos, low taxes, and small government tradition. Participants pledge to move and exert efforts toward a society where government’s role is limited to protecting life, liberty, and property.

Scale and Participation (as of late 2025)

- Pledges: Over 20,000 signed the Statement of Intent (goal reached in 2016).

- Actual Movers: Approximately 6,000–7,000 relocated to NH, plus thousands more aligned but not formally pledged.

- Community Impact: Hosts major events like PorcFest (annual liberty festival) and NH Liberty Forum; built networks for activism, business, and mutual aid.

This falls short of the original 20,000-mover vision but represents a significant influx into a state of ~1.4 million people.

Achievements as a Defense Against Subjugation

The FSP has contributed to policy wins enhancing individual autonomy and limiting coercive state power:

| Category | Key Achievements (Attributed to FSP Influence) | Impact on Subjugation |

|---|---|---|

| Gun Rights | Constitutional carry (permitless concealed/open carry); expanded Castle Doctrine (no duty to retreat). | Stronger negative rights to self-defense. |

| Tax & Fiscal Policy | Blocked state income/sales taxes; business tax cuts; low overall tax burden. | Reduces involuntary wealth transfer. |

| Education & Choice | Strengthened homeschooling freedoms; expanded school choice programs. | Empowers parental autonomy over state control. |

| Drug & Personal Freedoms | Marijuana decriminalization and medical legalization; civil asset forfeiture reforms. | Limits state intrusion into private choices. |

| Other | Deregulated cryptocurrency; rejected federal mandates (e.g., REAL ID, Obamacare exchange); court wins on filming police. | Resists federal coercion; enhances transparency. |

| Political Representation | Dozens of Free Staters elected to NH House (16+ in recent sessions); influence in Republican-majority legislature. | Direct voice in limiting government scope. |

New Hampshire consistently ranks #1 or #2 in freedom indices (e.g., Cato Institute’s Freedom in the 50 States—#1 in 2023 edition, highest score ever; top for fiscal policy, high for personal freedom). It has no income tax, low regulations, and strong gun/home-school protections—outcomes amplified by FSP activism.

Limitations and Criticisms

- Partial Success: Only ~30% of pledgers moved; influence is notable but not dominant (NH remains politically mixed).

- Backlash: Critics (e.g., Granite State Progress) view FSP as “extremists” seeking to dismantle public infrastructure (schools, roads); local controversies (e.g., Grafton “bear incident” from underfunded services) highlight risks of rapid deregulation.

- Not Full Secession: Extreme ideas (e.g., NH independence) remain fringe; no escape from federal subjection.

- Mixed Outcomes: Some efforts (e.g., deep budget cuts in small towns) reversed by voter turnout.

Overall Assessment as a Bulwark

| Metric | Rating (1–10) | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Reduction in State-Level Coercion | 8 | Tangible wins in taxes, guns, education—NH freer than most states. |

| Model for Consent-Based Governance | 6 | Demonstrates concentrated activism works, but still operates within non-consensual system. |

| Escape from Broader Subjugation | 4 | Limited to state policy; federal obligations (taxes, laws) unchanged. |

| Sustainability/Inspiration | 7 | Growing community/events inspire voluntarism; proves migration can shift culture. |

The FSP is a moderate bulwark—successful in making NH one of the least subjugating states domestically (low involuntary burdens via taxes/regulations) and proving that targeted migration + activism can expand negative liberties. It offers a practical alternative for those rejecting full anarchism but seeking less coercion. However, it hasn’t created a truly consensual society or fully nullified higher-level subjection. For individuals valuing liberty, moving to NH via FSP remains one of the strongest real-world strategies against everyday governmental overreach.

“For individuals valuing liberty, moving to NH via FSP remains one of the strongest real-world strategies against everyday governmental overreach”… … give me a strong 200-word pitch that NH is the Switzerland of America

Why New Hampshire is the Switzerland of America

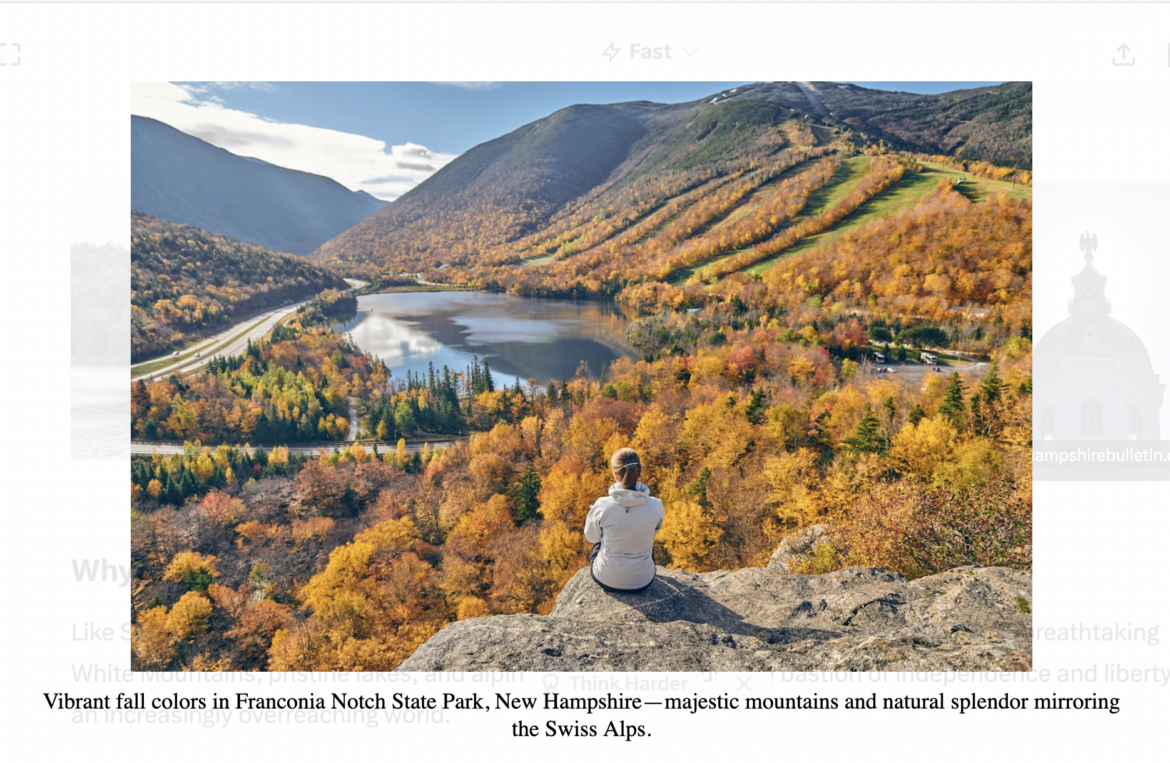

Like Switzerland, New Hampshire—long nicknamed the “Switzerland of America” for its breathtaking White Mountains, pristine lakes, and alpine scenery—stands as a bastion of independence and liberty in an increasingly overreaching world.

Both embody armed neutrality: Switzerland’s citizen militias and New Hampshire’s constitutional carry laws ensure a fiercely defended populace, ranking NH among the freest for gun rights.

Fiscally sovereign, NH boasts no state income or sales tax (fully phased out in 2025), mirroring Switzerland’s low-tax cantons that prioritize personal wealth and economic freedom. The Cato Institute ranks New Hampshire #1 in overall freedom, and the Fraser Institute crowns it the most economically free jurisdiction in North America.

Boosted by the Free State Project’s influx of liberty-minded movers, NH resists federal mandates, champions school choice, and minimizes government intrusion—offering a real-world refuge where “Live Free or Die” isn’t just a motto, but a way of life.

For those valuing true autonomy, New Hampshire isn’t just a state—it’s America’s alpine fortress of freedom. Join the movement and reclaim your liberty today.