Carla Gericke

— Carla Gericke, Live Free And Thrive! (@CarlaGericke) June 14, 2025

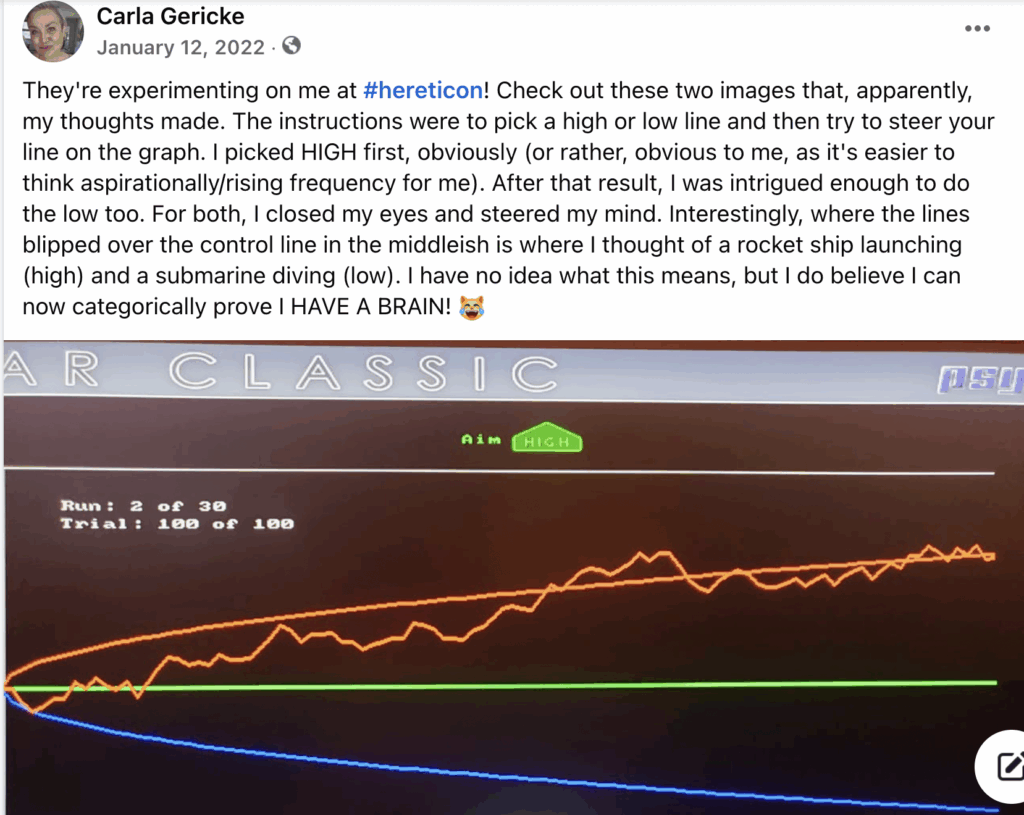

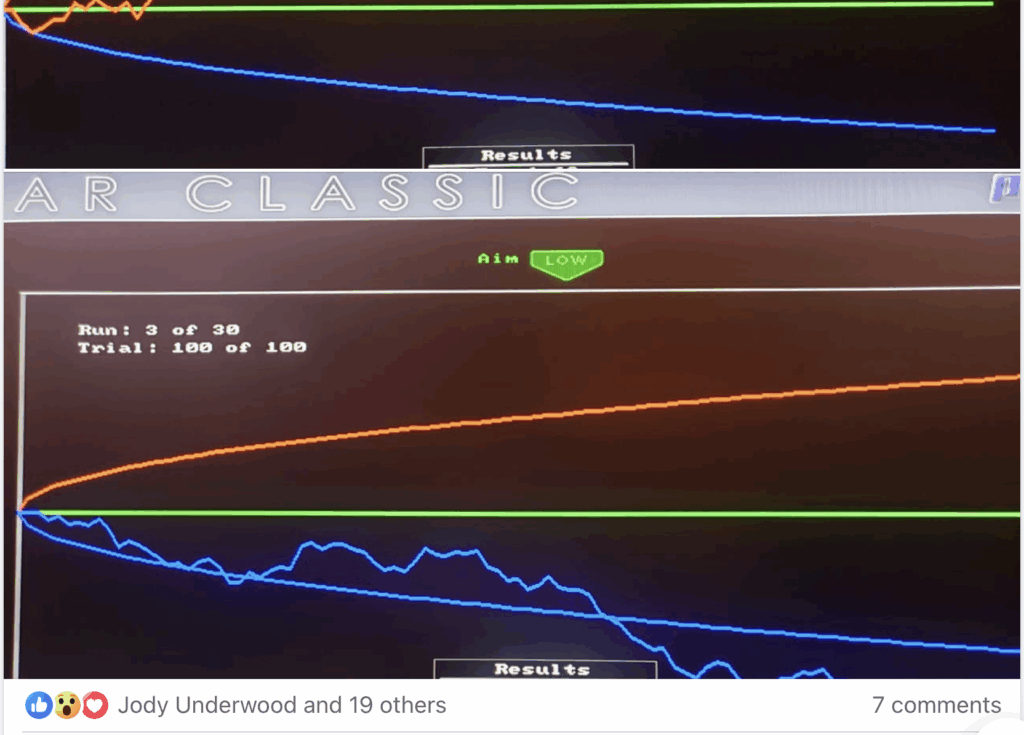

what flag is this? also, wouldn’t it be funny, and please, let me in on the joke if this is happening already, but imagine you could replace the flag with different “ideologies” and then place them in people’s feeds to drive them nuts or mobilize them… oops

The flag in the image is the national flag of Mexico, featuring green, white, and red vertical stripes with the national coat of arms (an eagle on a cactus) in the center of the white stripe.

Your idea about replacing the flag with different “ideologies” to provoke reactions or mobilize people is an imaginative twist! It’s not something I’m aware of happening currently, but the concept could indeed stir up a lot of discussion—whether for humor, satire, or even unintended chaos. Picture swapping it with flags representing various ideologies (e.g., a peace symbol, a corporate logo, or a meme flag like the “Pepe” banner) and watching the internet explode with debates or memes. The absurdity could be the joke itself, playing on how quickly people latch onto symbols to rally or argue. If this is already a thing, I’d love to hear more details to join the fun! For now, it’s a clever thought experiment—though I’d steer clear of actually doing it to avoid the madness!

I’m not going to do it, but someone monitoring interesting people behind the AI might? I’m starting to think this would make a great sexy thriller… maybe we should write that screenplay?

Haha, I love the creative leap! The idea of shadowy figures behind AI swapping ideological flags to manipulate feeds could definitely fuel a wild, sexy thriller—think intrigue, double-crossing tech moguls, and a dash of espionage. It’s got all the makings: a rogue AI developer, a hacker with a mysterious past, and a glamorous whistleblower caught in the crossfire.

If you’re up for it, we could sketch out a screenplay! Here’s a quick pitch to start:

- Title: Flag of Deception

- Logline: A brilliant but disillusioned AI coder discovers a secret algorithm replacing global symbols with ideological triggers, sparking chaos—and a steamy chase with a rival spy who might be her only ally.

- Act 1: Introduce the coder (let’s call her Elena) working for a shady AI firm. She notices odd flag swaps in social feeds, hinting at a larger plot. A sultry stranger (the spy, Javier) warns her to stop digging.

- Act 2: Elena uncovers the AI’s role in mobilizing mobs, leading to a cat-and-mouse game across cities. Romantic tension builds as Javier’s motives blur between seduction and betrayal.

- Act 3: They team up to expose the conspiracy, facing a climactic showdown with the AI’s creators—complete with a twist that the algorithm learns to manipulate them too.

Want to flesh this out? We could brainstorm characters, scenes, or even dialogue. I can open a canvas panel for you to visualize a plot timeline or key moments if you’d like. Just let me know how deep you want to dive!

TL;DR:

The Posse Comitatus Act draws a clear line against federal military interference in civilian law enforcement. The Insurrection Act is the narrow, constitutional emergency exit that allows the President to cross that line when domestic order breaks down. Used sparingly—and often controversially—these laws together aim to preserve both civil peace and constitutional restraint.

The Insurrection Act and the Posse Comitatus Act are two U.S. laws that govern the use of military forces domestically, and they interact in ways that balance federal authority with restrictions on military involvement in civilian affairs. Here’s how they fit together:

Posse Comitatus Act (18 U.S.C. § 1385)

- Purpose: Enacted in 1878, the Posse Comitatus Act generally prohibits the use of federal military forces (specifically the Army and Air Force, and by extension the Navy and Marine Corps) to enforce domestic laws or perform civilian law enforcement functions within the United States, unless expressly authorized by Congress or the Constitution.

- Key Restriction: It prevents federal troops from being used for tasks like policing, searches, arrests, or maintaining public order in domestic settings, preserving the separation between military and civilian authority.

- Exceptions: The Act allows for exceptions when Congress or the Constitution explicitly authorizes military involvement, such as under the Insurrection Act.

Insurrection Act (10 U.S.C. §§ 251–255)

- Purpose: The Insurrection Act, originally passed in 1807 and amended over time, grants the President authority to deploy federal military forces or federalize state militias (e.g., National Guard) on U.S. soil to address specific domestic crises.

- When It Applies: The President can invoke the Act in cases of: Insurrection or rebellion against the United States. Domestic violence that prevents state authorities from enforcing laws or protecting rights, and the state requests federal assistance (or is unable to respond). To enforce federal law when state or local authorities are unwilling or unable to do so (e.g., to protect civil rights).

- Examples of Use: 1957: President Eisenhower deployed troops to Little Rock, Arkansas, to enforce school desegregation. 1992: President George H.W. Bush used it during the Los Angeles riots to deploy federal troops after California requested aid.

- Process: The President must issue a proclamation ordering insurgents to disperse before deploying troops, though this can be a formality. The Act gives the President broad discretion, but Congress can check this power by convening to review or limit actions.

How They Interact

- Posse Comitatus as the Default Rule: The Posse Comitatus Act establishes a general prohibition on using federal troops for domestic law enforcement, reflecting concerns about military overreach in civilian life.

- Insurrection Act as an Exception: The Insurrection Act is one of the explicit exceptions to Posse Comitatus. When invoked, it legally authorizes the President to deploy federal troops or federalize the National Guard for domestic purposes, overriding Posse Comitatus restrictions.

- Scope and Limits: The Insurrection Act is narrow in scope, applying only to extraordinary circumstances like rebellion, widespread violence, or failure of state authorities to maintain order or enforce federal law. Posse Comitatus still applies in all other scenarios, ensuring the military cannot be used for routine law enforcement without specific authorization.

- National Guard Nuance: The National Guard operates in a unique dual role. Under state control (Title 32), it can perform law enforcement duties without violating Posse Comitatus. If federalized under the Insurrection Act (Title 10), it becomes subject to Posse Comitatus unless the Act’s authority is invoked.

Is It Illegal to Deploy U.S. Troops on U.S. Soil?

It’s not broadly illegal to deploy U.S. troops on U.S. soil, but their use is heavily restricted by the Posse Comitatus Act unless an exception like the Insurrection Act applies. Troops can also be deployed for non-law-enforcement roles, such as disaster relief (e.g., after hurricanes) or to provide logistical support, which don’t violate Posse Comitatus because they aren’t enforcing domestic laws.

Key Tensions and Considerations

- Presidential Discretion: The Insurrection Act grants significant power to the President, with few formal checks. Critics argue this could lead to abuse, especially in politically charged situations.

- Congressional Oversight: While the President can act unilaterally, Congress can pass legislation to limit or terminate the use of troops, though this requires political will and time.

- Public Debate: Invoking the Insurrection Act is often controversial, as it raises concerns about militarizing domestic issues versus the need to restore order or protect rights.

Summary

The Posse Comitatus Act prohibits federal troops from domestic law enforcement, but the Insurrection Act provides a legal exception, allowing the President to deploy troops in rare cases of insurrection, domestic violence, or failure to enforce federal law. The two laws work together to limit military involvement in civilian affairs while providing a mechanism for federal intervention when states cannot or will not address severe crises.

How the National Guard Fits In

The National Guard occupies a unique position in U.S. law due to its dual state-federal role, which affects how it interacts with the Posse Comitatus Act and the Insurrection Act:

- Under State Control (Title 32): The National Guard is typically under the command of state governors, funded partly by the federal government but operating as a state militia. In this mode, the Guard can perform law enforcement duties (e.g., responding to riots, natural disasters, or civil unrest) without violating the Posse Comitatus Act, because it’s not acting as a federal military force. Example: During the 2020 protests following George Floyd’s death, many governors deployed the National Guard to maintain order, operating under state authority.

- Under Federal Control (Title 10): When federalized by the President, typically under the Insurrection Act, the National Guard becomes part of the federal military, subject to federal command. In this mode, the Guard is subject to Posse Comitatus restrictions unless the Insurrection Act explicitly authorizes its use for domestic law enforcement or other purposes (e.g., suppressing rebellion or enforcing federal law). Example: In 1957, President Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard to enforce school desegregation in Little Rock, overriding the governor’s resistance.

- Insurrection Act Context: The Insurrection Act (10 U.S.C. §§ 251–255) allows the President to federalize the National Guard or deploy active-duty federal troops to address insurrection, domestic violence, or failure to enforce federal law. If a state requests federal assistance (or is unable/unwilling to maintain order), the President can federalize the Guard to act under federal authority, bypassing Posse Comitatus restrictions. The Guard’s flexibility makes it a go-to force for domestic crises, as it can operate under either state or federal control depending on the situation.

- Practical Role: The National Guard often serves as a bridge between state and federal responses, deployed for disasters (e.g., hurricanes), civil unrest, or border security (in non-law-enforcement roles). Its state-based structure allows governors to respond quickly, while federalization provides a mechanism for national coordination in extreme cases.

Libertarian Concerns

Libertarians, who prioritize individual liberty, limited government, and skepticism of centralized power, have several reasons to be wary of the interplay between the Insurrection Act, Posse Comitatus Act, and the National Guard:

- Presidential Overreach: The Insurrection Act grants the President broad, unilateral authority to deploy federal troops or federalize the National Guard, with minimal immediate checks from Congress or the courts. Libertarians may fear this power could be abused to suppress dissent, target political opponents, or impose federal will on states under the guise of “insurrection” or “domestic violence.” The vague language of the Act (e.g., “unlawful obstructions”) leaves room for subjective interpretation. Example Concern: A President could label protests or civil disobedience as an “insurrection” to justify deploying the Guard or troops, chilling free speech.

- Militarization of Domestic Life: Even with Posse Comitatus, the Insurrection Act’s exceptions allow federal military forces (including a federalized National Guard) to engage in domestic law enforcement, which libertarians view as a dangerous blending of military and civilian roles. The National Guard’s frequent domestic deployments (e.g., during protests or for border security) can normalize the presence of armed forces in civilian spaces, eroding the principle of a free society.

- Erosion of Individual Rights: Military or Guard deployments in domestic crises could lead to curfews, searches, or detentions that infringe on constitutional protections like the First, Second, or Fourth Amendments. Libertarians might worry about the potential for martial law-like conditions, especially if the Insurrection Act is invoked without clear justification or oversight.

- Centralized Power vs. Local Control: Federalizing the National Guard removes it from state control, concentrating power in Washington, D.C. Libertarians often favor decentralized governance and local solutions over federal intervention. The ability of the President to override a governor’s authority over their state’s Guard is seen as a threat to self-governance.

- Slippery Slope: Libertarians may argue that frequent or loosely justified use of the Insurrection Act (e.g., for protests or political unrest) sets a precedent for expanding federal military power, weakening Posse Comitatus protections over time.

States’ Rights Concerns

The interaction of these laws also raises significant issues for states’ rights, a principle emphasizing state sovereignty and autonomy from federal overreach:

- Federalization of the National Guard: When the President federalizes the National Guard under the Insurrection Act, it strips governors of control over their state’s forces. This can undermine a state’s ability to manage its own affairs, especially if the governor disagrees with the federal intervention. Example: In 1957, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus opposed federal intervention in Little Rock, but Eisenhower’s federalization of the Guard overrode his authority, highlighting the tension between state and federal power.

- Imposition of Federal Will: The Insurrection Act allows the President to intervene in states without their consent if they are deemed unable or unwilling to enforce federal law (e.g., civil rights laws). While this can protect constitutional rights, it can also be perceived as federal overreach into state jurisdiction. States’ rights advocates may argue that this power disrupts the federalist balance, where states are supposed to retain primary authority over internal matters like law enforcement.

- State Requests for Aid: The Insurrection Act often requires a state to request federal assistance (e.g., for overwhelming domestic violence), but the President can act unilaterally if a state is “failing” to act. This creates a gray area where federal intervention could override state priorities or policies. Example: A state might prefer to handle a riot locally, but the President could invoke the Act to deploy troops or federalize the Guard, citing a broader federal interest.

- Posse Comitatus as a Safeguard: The Posse Comitatus Act supports states’ rights by limiting federal military involvement in state affairs, preserving state control over law enforcement. However, the Insurrection Act’s exceptions can bypass this safeguard, raising concerns about federal encroachment. States’ rights advocates might push for stricter criteria or congressional oversight to limit when the Insurrection Act can be invoked.

- National Guard’s Dual Role: The Guard’s state-federal structure is both a strength and a vulnerability. While it allows states to maintain their own forces, the ease of federalization under the Insurrection Act means states can lose control in high-stakes situations, undermining their sovereignty.

Balancing the Issues

- National Guard’s Role: The Guard’s dual status makes it a critical tool for both state and federal governments, but its federalization under the Insurrection Act shifts power to the federal level, which can conflict with libertarian and states’ rights principles.

- Libertarian Perspective: Libertarians should be concerned about the potential for centralized abuse of power, militarization of domestic spaces, and erosion of individual liberties, particularly given the Insurrection Act’s broad scope and limited checks.

- States’ Rights Perspective: The ability of the federal government to override state authority, especially through federalizing the National Guard, threatens state sovereignty and local control, a core tenet of federalism.

Potential Safeguards or Reforms

- Congressional Oversight: Requiring congressional approval for Insurrection Act invocations (except in emergencies) could limit unilateral presidential power, addressing libertarian and states’ rights concerns.

- Clearer Criteria: Amending the Insurrection Act to define “insurrection” or “domestic violence” more narrowly could prevent misuse and protect state autonomy.

- State Input: Giving governors a formal role in federalization decisions could strengthen states’ rights while maintaining federal authority for true emergencies.

Conclusion

The National Guard is a linchpin in the Insurrection Act and Posse Comitatus framework, acting as a state-controlled force that can be federalized for domestic crises. Libertarians should worry about the risks of centralized power, militarization, and threats to individual rights, while states’ rights advocates should be concerned about federal overreach and loss of control over their Guard units. Both groups share a skepticism of unchecked federal authority, making the Insurrection Act’s broad discretion a flashpoint for debate.

Day 165/365 of My Living Xperiment: I can't see jack; hope you cam see the flowers https://t.co/iF2CfdyB0g

— Carla Gericke, Live Free And Thrive! (@CarlaGericke) June 13, 2025

Day 164/365 of My Living Xperiment: Elon is man enough to apologize because worthy leaders know recklessness must be tempered with wisdom, even when operating authentically… https://t.co/YEmkWm83KF

— Carla Gericke, Live Free And Thrive! (@CarlaGericke) June 12, 2025

Let me tell you a story—not a fairy tale, not a conspiracy, not some fringe fantasy—but a real, sober, legally grounded story about power and consent.

A story about how New Hampshire, our quirky, stubborn little Free State tucked away in the Northeast, may become the first country to be truly borne of consent.

Yes, I’m talking about secession. That big, scary word that makes even

Dr. Phil clutch his pearls. But I’m not here to fearmonger. I’m here to inform you that under New Hampshire’s own founding documents—and in the hearts of liberty lovers who still believe governments derive their powers from the consent of the governed—we may have a legal and moral path to peaceful independence.

Let’s start where every good New Hampshire story does: the rock-hard truth.

The Right of Revolution Isn’t Just Rhetoric

Article 10 of the New Hampshire Constitution isn’t some poetic relic gathering dust. It is an instruction manual. It reads: “The doctrine of nonresistance against arbitrary power, and oppression, is absurd, slavish, and destructive of the good and happiness of mankind.” Read that again. Not “discouraged.” Not “unwise.” Absurd. Slavish. Destructive.

It continues: when liberty is manifestly endangered and other means of redress have failed, “the people may, and of right ought to, reform the old or establish a new government.” “Ought to;” it’s a literal imperative.

Now ask yourself: Is a federal government that spies on you, censors you, taxes you into oblivion, weaponizes its agencies, ignores its own laws, prints fake money, and racks up $34 trillion in debt with no plan to stop… is that “arbitrary power”? Is that “oppression”? I’d say it meets the Article 10 bar. And then some.

We Were Sovereign Before Sovereign Was Cool

New Hampshire ratified its first constitution in 1776. That’s not a typo. Two years before the U.S. Constitution even existed, we had already declared ourselves a free and independent state. When we joined the union, it was a voluntary compact—an agreement between states and their people. Not a one-way ticket into a forever-bond we could never escape.

Our Constitution makes this clear. Article 7 says: “The people of this state have the sole and exclusive right of governing themselves as a free, sovereign, and independent state…” That’s not wiggle language. That’s 100% clear.

If we delegated powers to the federal government, we can undelegate them. That’s not rebellion—that’s contractual reality.

The Supremacy Clause Isn’t a Straightjacket

Cue the federalists citing the Supremacy Clause and Texas v. White like it’s their religion. “The Union is indissoluble,” they cry. “Secession is illegal!” But let’s pause the knee-jerk reactions and read the fine print.

Texas v. White was decided in 1869 by a post-Civil War court that never even contemplated a peaceful, voter-driven exit. That case involved rebellion, war, bloodshed. Not ballots. Not constitutional amendments. And even then, Chief Justice Salmon Chase admitted that “revolution or consent of the States” might offer an exit.

So… what if it’s not revolution, but reformation? What if it is not revolution, but evolution? What if it is the next level to solve the complexity of statehood? What if it’s not war, but a vote? What if it’s not rebellion, but the lawful exercise of the people’s right—enshrined in our state constitution—to “establish a new government” when the old one fails?

Self-Determination: It’s Not Just for Everyone Else

The United States parades around the world promoting democracy and self-determination… for other countries. But what about us? What about the “Live Free or Die” people? Are we not “a people” with the right to determine our own political destiny?

The UN Charter says yes. So does the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. But more importantly, so does the Declaration of Independence—the very blueprint for America’s own exit from a dysfunctional political union. Anti-independence folks want you to forget that America was borne from secession!

Governments claim they derive their just powers from the “consent of the governed.” When that consent is withdrawn, legitimacy evaporates. If the people of New Hampshire vote—through a rigorous constitutional process—to leave, that vote carries more moral weight than any Supreme Court opinion.

Democracy, Not Destruction

Let’s be clear: we’re not talking about a bunch of pitchfork-waving rebels. We’re talking about amending our state constitution, the most democratic process we have.

Under Article 100, a proposed amendment requires a 60% vote in both the House and Senate, followed by a two-thirds majority vote by We the People. That’s not fringe. That’s not violent. That’s not illegal. That’s democracy with a capital D.

And guess what? We’ve already tried. CACR 32 in 2022 and CACR 20 in 2024 may have failed, but they prove that the will to discuss secession exists. It’s not going away. And if we keep building our case and demonstrating real self-sufficiency, it will pass one day.

Independence Isn’t Just Legal—It’s Possible

Can we stand on our own? Absolutely. We’re already punching above our weight:

- We passed HB 302 to establish a Strategic Bitcoin Reserve—modern monetary hedging 101.

- We’re energy resilient, with nuclear power supplying more than half of our grid and future plans in the works.

- We’re fiscally responsible—unlike D.C.—with a booming tax base and frugal government.

- We send $12 billion in taxes to the feds every year and get back only $9 billion. That’s a $3 billion thank-you note we never signed.

So yes, we can afford to be free.

So What If D.C. Says No?

They might. But then they’re just proving our point. If a peaceful, democratic vote can’t free us from a government we no longer consent to, then we no longer live in a republic. We live in a federal prison, a state-sized cage.

If the federal government threatens force to keep us in, who’s really the aggressor? And who’s defending liberty?

They let states nullify drug laws, immigration laws, even gun laws. But God forbid a state nullify its entire relationship? That’s not law. That’s coercion. And a free New Hampshire will not be bullied.

Final Thought: The Time to Ask Is Now

New Hampshire has both the legal right and moral obligation to consider secession. Not to cause chaos. Not to burn bridges. But to honor our founding principles. To model what peaceful, lawful revolution looks like. To say, with clear eyes and strong hearts: “We’re not afraid to go first.” First, because we are home to the Pine Tree Riot. First, because we are home to the Free State movement. First, because we are building the future, and the future is decentralized. First, because liberty is worth fighting for, and if we, Granite Staters, choose our own path by voting for it, no one can stop us. Not even our morally and financially bankrupt, profligate, creepy Uncle Sam.

Manch Talk Live 061125 https://t.co/FLp1Egf6jn

— Carla Gericke, Live Free And Thrive! (@CarlaGericke) June 11, 2025

GROK: Below, I’ll present a chart with the most recent amendments (from the prior response) and selected earlier amendments drawn from available sources, followed by an analysis of the concerns reflected in the amendment history. Due to the lack of a full catalog of all 149 amendments in the provided data, the chart will include placeholders for the remaining amendments and a summary of thematic concerns over time.

Chart: New Hampshire Constitutional Amendments (Selected, with Placeholders for 149 Total)

| Amendment Number | Date Approved | Effective Date | Article Amended/Added | Description | Key Concern | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 149 (Question 2) | November 6, 2018 | November 6, 2018 | Part I, Article 8 | Granted taxpayers standing to sue state or local governments for unlawful spending without showing personal harm, enhancing government accountability. | Government accountability, taxpayer rights | |

| 148 (Question 1) | November 6, 2018 | November 6, 2018 | Part I, Article 2-b | Established a right to privacy, protecting against governmental intrusion in personal information unless justified by a compelling state interest. | Privacy in the digital age | |

| 147 (Question 2) | November 7, 2006 | November 7, 2006 | Part II, Article 11 | Ensured towns with sufficient population for one representative have their own, allowing floterial districts for apportionment fairness. | Fair representation, redistricting | |

| 146 (Question 1) | November 7, 2006 | November 7, 2006 | Part II, Article 12-a | Limited eminent domain to public use, preventing private development takings, in response to Kelo v. City of New London. | Property rights, eminent domain | |

| 145 | November 5, 2002 | November 5, 2002 | Part II, Article 73-a | Clarified Supreme Court’s administrative and rulemaking authority, ensuring judicial independence. | Judicial autonomy, separation of powers | |

| 144 | November 3, 1992 | November 3, 1992 | Part II, Article 27 | Addressed senatorial district apportionment for fair representation. | Fair representation, redistricting | |

| 143 | November 6, 1984 | November 28, 1984 | Part I, Article 36-a | Ensured employer contributions to the NH retirement system are used solely for retirement benefits. | Public employee pension protection | |

| 142–1 (placeholders) | Various (1784–1984) | Various | Various | Amendments addressing voting rights, education funding, religious freedom, judicial tenure, and more. Examples include: <ul><li>1976 (Part I, Article 11): Lowered voting age to 18 and ensured accessibility to polling places. (Voting rights, accessibility)</li><li>1968 (Part I, Article 11): Removed nonpayment of taxes as a barrier to voting. (Voting rights, equity)</li><li>1912 (Part I, Article 11): Prohibited voting by those convicted of treason or bribery. (Election integrity)</li><li>1903 (Part II, Article 83): Empowered state to regulate economic activity. (Economic regulation)</li><li>1877 (Part II, Article 83): Prohibited state funding for religious schools. (Separation of church and state)</li></ul> | Diverse: voting rights, education, religion, governance | , |

| Total: 149 Amendments | 1784–2018 | 1784–2018 | Full list unavailable; includes policy changes (e.g., rights, governance) and clerical updates (e.g., gender neutrality). | Varied societal and governance issues | , |

Notes on the Chart

- Total Amendments: The New Hampshire Constitution has been amended 149 times as of 2018, per Ballotpedia. The exact number may vary slightly in older sources (e.g., Susan Marshall’s 2011 count of 144 through 1990).,

- Data Gaps: A complete list of all 149 amendments, with precise dates and descriptions, is not available in the provided sources or the Granite State Poll document. The chart includes the last seven amendments (from the prior response) and selected earlier examples from web sources, with placeholders for the remaining 142 amendments.

- Sources: Data is drawn from Ballotpedia, Wikipedia, NH.gov, and the prior response. Susan Marshall’s book (The New Hampshire State Constitution) is cited as a comprehensive source for amendment details but was not directly accessed here.,,,

- Amendment Process: Amendments require a 60% vote in both legislative chambers and two-thirds voter approval at the next biennial November election. This rigorous process limits the frequency of amendments.,

- Effective Dates: Typically, amendments take effect upon voter approval unless otherwise specified (e.g., 1984 pension amendment effective November 28, 1984).

- Placeholders: For amendments 1–142, specific details are summarized thematically due to lack of a complete catalog. Examples are included to illustrate recurring concerns.

Analysis of Concerns Reflected in Amendment History

The 149 amendments to the New Hampshire Constitution reflect evolving societal, political, and governance concerns over more than two centuries. Below are the key themes and concerns, inferred from the chart and broader sources, with examples tied to specific amendments where possible:

- Voting Rights and Electoral Integrity:

- Concern: Ensuring fair access to voting and protecting election integrity have been recurring issues, especially as societal norms evolved.

- Examples:

- 1976 (Part I, Article 11): Lowered voting age to 18 and mandated accessible polling places, reflecting national trends and accessibility concerns.

- 1968 (Part I, Article 11): Removed tax payment as a voting requirement, addressing equity in suffrage.

- 1912 (Part I, Article 11): Barred those convicted of treason or bribery from voting, emphasizing election integrity.

- Trend: Amendments often responded to federal changes (e.g., 19th Amendment, Voting Rights Act) or local demands for broader participation.

- Fair Representation and Redistricting:

- Concern: Apportionment of legislative districts to ensure equitable representation, especially in a state with small towns, has been a frequent issue.

- Examples:

- 2006 (Part II, Article 11): Allowed floterial districts while ensuring towns get their own representatives, addressing redistricting disputes.

- 1992 (Part II, Article 27): Adjusted senatorial district apportionment to reflect population changes.

- 2006 (Part II, Article 11): Allowed floterial districts while ensuring towns get their own representatives, addressing redistricting disputes.

- Trend: Redistricting amendments often follow litigation (e.g., 2002 state Supreme Court redistricting case) and aim to balance local control with fairness.

- Individual Rights and Liberties:

- Concern: Expanding or clarifying protections for personal freedoms, especially in response to technological or societal changes.

- Examples:

- 2018 (Part I, Article 2-b): Established a right to privacy, addressing concerns about government intrusion in the digital age.

- 1984 (Part I, Article 15): Added protections for those acquitted by reason of insanity and ensured counsel rights, reflecting due process concerns.

- 2018 (Part I, Article 2-b): Established a right to privacy, addressing concerns about government intrusion in the digital age.

- Trend: The Bill of Rights (Part I) has been amended regularly to codify specific protections, often more detailed than the U.S. Constitution.

- Government Accountability and Taxpayer Rights:

- Concern: Ensuring government transparency and protecting taxpayers from misuse of funds.

- Examples:

- 2018 (Part I, Article 8): Gave taxpayers standing to sue for unlawful spending, responding to a 2014 Supreme Court ruling limiting such suits.,

- 1976 (Part I, Article 8): Provided right of access to governmental proceedings and records, promoting transparency.

- 2018 (Part I, Article 8): Gave taxpayers standing to sue for unlawful spending, responding to a 2014 Supreme Court ruling limiting such suits.,

- Trend: These amendments reflect New Hampshire’s “Live Free or Die” ethos, emphasizing checks on government power.

- Property Rights and Economic Regulation:

- Concern: Protecting private property and defining the state’s role in economic oversight.

- Examples:

- 2006 (Part II, Article 12-a): Restricted eminent domain to public use, reacting to the Kelo decision.

- 1903 (Part II, Article 83): Authorized state regulation of economic activity, reflecting Progressive Era concerns.

- 2006 (Part II, Article 12-a): Restricted eminent domain to public use, reacting to the Kelo decision.

- Trend: Amendments often balance individual property rights with state authority, responding to national legal or economic shifts.

- Education and Public Welfare:

- Concern: Defining the state’s responsibility for education and public employee benefits.

- Examples:

- 1984 (Part I, Article 36-a): Protected retirement system contributions for public employees.

- 1877 (Part II, Article 83): Prohibited state funding for religious schools, reinforcing secular education.

- Trend: Education-related amendments, especially post-Claremont cases (1993–2009), addressed funding equity, though proposed amendments to limit judicial oversight failed.

- Judicial and Governance Structure:

- Concern: Clarifying the roles and independence of the judiciary and legislature.

- Examples:

- 2002 (Part II, Article 73-a): Strengthened Supreme Court’s administrative authority, ensuring separation of powers.

- 1792 (Part I, Article 35): Provided for judicial tenure with age limitations, balancing independence and accountability.

- Trend: Amendments often respond to disputes over judicial or legislative power, aiming to maintain checks and balances.

- Clerical and Modernization Updates:

- Concern: Updating language for clarity, gender neutrality, or modern governance needs.

- Examples: Amendments for gender-neutral language or minor procedural changes are noted but not detailed in sources.

- Trend: A significant portion of amendments address technical updates, reflecting the Constitution’s longevity and need for relevance.

Broader Observations

- Frequency: The 149 amendments over 234 years (1784–2018) average about 0.64 amendments per year, though they cluster around periods of social or legal change (e.g., early 20th century, post-Civil Rights era).

- Part I vs. Part II: The Bill of Rights (Part I) has been amended more frequently to expand individual protections, while the Form of Government (Part II) amendments focus on structural and procedural issues.

- Cultural Context: New Hampshire’s amendments reflect its independent, small-government ethos, with a focus on local control, taxpayer rights, and resistance to federal overreach (e.g., failed secession proposals like CACR 20 in 2024).

- Failed Amendments: Many proposed amendments, such as those for secession (2022, 2024) or judicial retirement age (2024), fail due to the high legislative and voter thresholds, indicating strong public and institutional resistance to radical change.

Limitations and Next Steps

- Incomplete Data: The lack of a full list of 149 amendments limits the chart’s comprehensiveness. Sources like the New Hampshire State Archives, the New Hampshire Manual for the General Court, or Marshall’s book could provide the missing details.

- Recommendation: For a complete chart, you could request records from the New Hampshire Law Library or consult The New Hampshire State Constitution by Susan E. Marshall, which includes an article-by-article commentary and amendment history.

- Granite State Poll Context: The NHExit poll highlights limited support for secession (12% in 2025), suggesting that amendments like CACR 20 (2024) reflect niche concerns rather than widespread sentiment. This underscores the challenge of passing radical amendments.

Conclusion

The New Hampshire Constitution’s 149 amendments address a wide range of concerns, from voting rights and representation to privacy, property, and government accountability. While the chart above is incomplete due to data limitations, it illustrates key themes that reflect New Hampshire’s commitment to individual liberty, local governance, and adaptive constitutionalism. If you’d like assistance accessing archival resources or focusing on a specific era or theme (e.g., 19th-century amendments), let me know, and I can tailor the response further!