Carla Gericke

Let’s play a game: Let’s pretend Elon Musk decided he’s done tweeting about the collapse of civilization and actually wants to do something about it NOW. Not with another AI chatbot or Martian colony (although, yes please, Mars sounds fab, save me a seat!), but with the boldest move since 1776:

Fifty mini-revolutions.

Not with guns, but ideas. Not by tearing it down, but by building new from the inside out. A decentralized “America First” political movement—state by sovereign state. Think: New Hampshire First; Texas First; California First (I know, lol, but maybe, they have CALExit, at least); [Insert-Your-State-Here First].

A national framework, sure—but with all the real action happening locally. It’s federalism on fire. Nullify federal overreach. Defend local autonomy. Restore the American experiment, one state at a time. And yes, leverage existing Libertarian Party networks, because guess what? We’re already here, we’ve already been doing the work, and we’re ready. At least here in New Hampshire, we are, where thousands of libertarians have quietly been building the freest state in the nation.

Strategy (aka How to Build the Decentralized Death Star of Freedom)

1. Launch “America First” as a Real Platform

But make it sexy: A bold new brand that says, “We’re done asking permission.” Mission: State sovereignty. Individual liberty. Resistance to the bureaucratic Borg. Each state chapter gets to tailor their rebellion—but we’re rowing in the same direction.

2. Tap into the Libertarian Network

We already have state-level LP structures filled with battle-scarred activists, candidates, and visionaries who’ve been fighting the feds since before it was cool. Throw in some training, tech, and treasure, and you’ve got an army of Gandalf-meets-Gadsden flaggers ready to roll.

3. Launch State-Level “First” Orgs

Each state gets its own “First” crew. They decide how best to tell the feds to kick rocks: maybe it’s nullifying ATF overreach in Wyoming, or telling the DEA to take a hike in Colorado. Customize the rebellion to the terrain. That’s how you win. Or… throw everything at them all at once? Overwhelm a sinking ship.

4. Musk, Meet Meaning

Use X, your media gravity, and, yes, your stacks of cash to amplify the mission. Want to be a hero? Be the guy who finally turned the tide against the federal Leviathan. Build the tech stack. Build the culture. Build the tools of resistance and principle. But let’s do it right: Decentralized. Restore the laboratories of freedom, federalism, states’ rights, and each state’s right to “try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.”

5. Nullification as a Legal and Political Sword

Draft model laws. Elect liberty-first candidates. Defund federal parasites (or primary them). Say no—loudly and often. From the EPA to the FBI to the Dept. of Ed, the alphabet soup is expired. It’s time to put the garbage out.

Why This Works (aka The Pros)

- Decentralized = Durable Power to the people, not the swamp. The Tenth Amendment was never repealed, just ignored. Let’s dust it off.

- LP Infrastructure Exists It’s not perfect (see: internal drama), but it’s functional. And has a structure to leverage.

- Localism Wins Hearts Talk to Texans about guns. Talk to Vermonters about hemp. Tailor your nullification, win your battles.

- There’s Precedent Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions. Cannabis nullification. Sanctuary cities. Real history, real results.

Real Talk (aka The Cons)

- Legal Knife Fights Incoming The feds sue. That’s their move. But each suit spreads the message and shifts the Overton window. Lawfare is just part of the terrain.

- The “Extremist” Label Will Come The regime will call it sedition. The media will freak. That means it’s working. (Ask me how I know. :))

- LP Drama Llamas The party isn’t perfect. But it’s real, and it’s already decentralized. Pick your battles, build what works, skip what doesn’t.

- Federal Bribes Will Be Threatened Highways. Education. Healthcare. The feds will say, “Play our game or lose your funding.” It’s extortion. Don’t blink. (Also, it’s funded by fiat debt, so is it even real money?)

- Elon’s Polarizing You’ll gain some, you’ll lose some. But if you stay focused on the principles—freedom, decentralization, unity—you can keep the tent big enough for liberty-curious moderates, disaffected independents, and fed-up lefties. Scoop up the antiwar folks, the vaccine harmed folks, the middle class.

Implementation Blueprint

- Pilot in Friendly States Start in NH because of the Free State Project—and Texas and Florida, where liberty already has deeper roots.

- Lawyer Up Wisely Use constitutional experts to craft watertight nullification bills. Avoid unnecessary losses.

- Narrative Framing Matters This isn’t about tearing down. It’s about building something better. Localism. Accountability. Dignity. Freedom. Decentralization. Unity.

- Coalitions Win Wars Gun rights groups, homeschoolers, crypto bros, permaculturists, antiwar veterans—we’re all fighting the same creepy Uncle Sam. Unite. (We have done this successfully in the Free State of New Hampshire.)

The Punchline

A decentralized “America First” movement could be the greatest political innovation of our time—if we get it right.

Don’t centralize the rebellion. Don’t wait for DC to change. [<—YOU ARE HERE] Don’t ask permission to be free.

Just start building.

And Elon? If you’re reading this? Let’s go! I’m standing by to help!

— Carla Gericke, Live Free And Thrive! (@CarlaGericke) June 29, 2025

My Living Xperiment: Day 180

Day One Eighty of My Living Xperiment: Rigging the party porch! https://t.co/iLnSaCYvPe

— Carla Gericke, Live Free And Thrive! (@CarlaGericke) June 28, 2025

Day 179 of My Living Xperiment: A word that straddles imagination and admiration for today's 420 Ramble… https://t.co/O5zvS8kJiO

— Carla Gericke, Live Free And Thrive! (@CarlaGericke) June 27, 2025

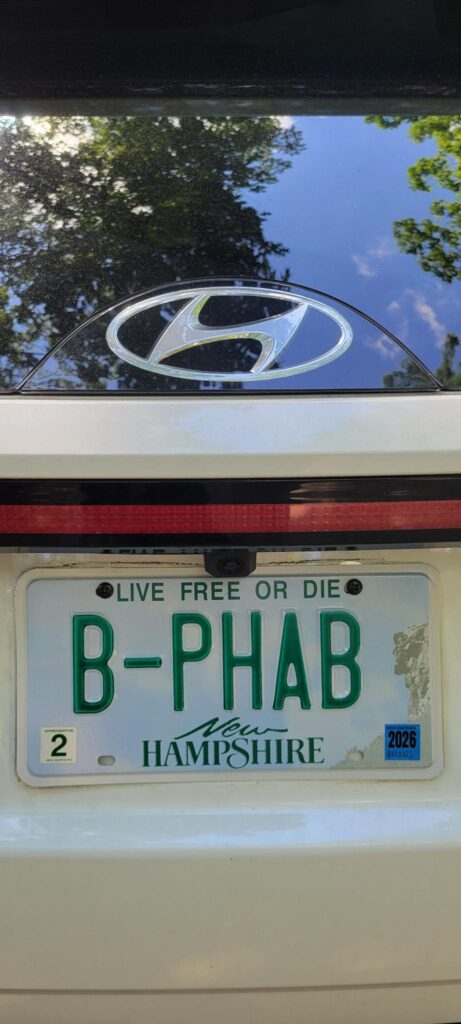

Whatta thrill today when I went to open the back of my new car to release Obi at the trailhead, and saw my vanity license plate for the first time.

The word “fabulous” has a delightfully rich history, rooted in storytelling and wonder. Here’s a breakdown:

🔤 Etymology of “Fabulous”

- Origin: Latin

- Latin Root: fabulosus

- From fabula = “story, fable, narrative”

- Fabula itself comes from fari = “to speak, tell”

So, originally, fabulosus meant something like “pertaining to stories or fables” — things that are imaginary, legendary, or unbelievable.

📚 Evolution in English

- Late Middle English (1400s):

“Fabulous” enters English meaning “mythical, legendary, related to fables”, i.e., not real, fantastical. - 1600s onward:

The meaning starts to stretch toward the extraordinary or hard to believe, e.g., “fabulous wealth.” - Mid-20th Century (especially in American English):

The word gets a slang upgrade to mean “extremely good,” “wonderful,” “stylish,” or “amazing” — think Hollywood glamour, fashion, or a diva’s compliment.

✨ Modern Usage

Today, “fabulous” can mean:

- Fictional or mythological (e.g., “fabulous beasts”)

- Extremely good or impressive (e.g., “That dress is fabulous!”)

- Used in queer and drag culture as a campy superlative (e.g., “You look absolutely fabulous, darling!”)

🧠 Related Words

- Fable: a short story with a moral

- Fabulist: someone who tells fables — or lies

- Fiction: a cousin in the world of the imagined

🌈 TL;DR

“Fabulous” started as a word about fables and fantasy, and morphed into a celebration of things so good, they feel almost unreal. It’s a word that straddles imagination and admiration — a sparkle from Latin lore to modern slang.

more along these lines: It’s a word that straddles imagination and admiration… give me some references from art

Absolutely. “Fabulous” is one of those words that shimmers with double meaning—rooted in fable (myth, magic, storytelling) and now used for style, excess, glamor, awe. It stands at the crossroads of imagination and admiration, as you said. Below are some rich artistic and cultural references that show how “fabulous” has straddled those worlds:

🎭 Classical Art & Myth

- “Fabulous beasts” in medieval manuscripts and ancient mythologies:

These are not just imaginary animals (griffins, unicorns, chimeras), but symbols of moral or cosmic truth. The term fabulous here means both unreal and extra-significant.- See: Bestiaries of the Middle Ages

- Dürer’s Rhinoceros (1515), which was drawn based on a description, not direct observation—a fabulous rendering of a real creature.

- Ovid’s Metamorphoses:

A fountainhead of fabulous stories—gods transforming mortals, men becoming stars, lovers turned into trees. The fabulous here is the transformative power of story.

💃 Baroque & Rococo Excess

- The 17th and 18th centuries leaned into the fabulous—extravagant, theatrical, dripping with gold and silk. Think:

- Versailles: Louis XIV didn’t just build a palace, he built a fabulous fantasy of divine right and celestial glory.

- Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Swing (1767): flirtation, lushness, mythic gardens—delight made visual.

✨ Fashion and Glamour

- Elsa Schiaparelli, surrealist fashion designer:

Her work with Dalí (lobster dresses, shoe hats) is literally fabulous—unreal, dreamlike, admired. She once said, “In difficult times, fashion is always outrageous.”

→ That outrageousness became synonymous with fabulousness. - Studio 54 Era (1970s):

The word fabulous became cultural currency.- Think Andy Warhol, Grace Jones, Halston, Bianca Jagger on a white horse—all embodiments of fabulous as elevated mythmaking in real life.

🏳️🌈 Queer Culture & Drag

- Fabulous became a form of identity armor and self-expression—owning one’s difference and daring to shine.

- RuPaul: “You’re born naked and the rest is drag.” Every layer after that? A fabulous invention.

- In this context, “fabulous” reclaims the fantastical, turning it into a power move. Not fake—fierce.

🖼️ Modern & Contemporary Art

- Jeff Koons’ balloon animals and Takashi Murakami’s psychedelic color explosions live in the land of fabulous—glossy, surreal, high and low all at once.

- Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Rooms are literally fabulous: step inside and leave the real world behind.

🧵 In Sum:

Fabulous is a thread that runs through:

- The unreal and the ideal,

- The imaginary and the iconic,

- The fable and the famous.

It’s not just about fantasy—it’s about elevation, adornment, awe. It’s what happens when storytelling puts on heels and struts into the spotlight.

Dürer’s Rhinoceros (1515) show me

Here is Albrecht Dürer’s famous Rhinoceros (1515) – one of the most iconic “fabulous” creatures in Western art:

🐘 About the Image:

- Dürer never saw a rhinoceros in real life.

- He based this woodcut on a written description and a sketch by someone who had seen it in Lisbon, where the first rhino in Europe in over 1,000 years had arrived.

- The result? An animal with armor-like plates, decorative rivets, and an extra horn on its back—a fabulous creature, part real, part myth.

Why It Matters:

This rhinoceros was treated like a marvel, a beast of wonder, a symbol of power and the exotic. Even though it’s inaccurate, the image was so compelling it became the standard European depiction of a rhino for centuries.

It’s the perfect example of “fabulous” in its original sense: mythologized, exaggerated, and beloved for its audacity.

What does fabulous mean, GROK?

“Fabulous” means extraordinary, especially extraordinarily large or impressive; wonderful or marvelous. It can describe something or someone exceptionally good, pleasing, or striking, often with a sense of enthusiasm or flair. For example, “She looked fabulous in her new dress” or “The party was absolutely fabulous!” It’s rooted in the word “fable,” implying something almost mythical in its greatness.

The etymology of “fabulous” is quite rich, reflecting its journey from ancient storytelling to modern exuberance. The word originates from the Latin fabulosus, which means “celebrated in fables” or “mythical.” This derives from fabula, meaning “story,” “tale,” or “fable,” often carrying a sense of something legendary or extraordinary. Fabula itself stems from the Proto-Indo-European root bha-, which means “to speak, tell, or say,” a root that also underpins words like “fame” and “banter.”

In its early Latin usage, fabulosus was tied to the realm of myth and narrative, describing things so grand or fantastical they belonged in stories. By the time it reached Old French as fableux (around the 13th century), it began to take on a broader sense of “marvelous” or “wonderful.” When it entered Middle English in the 15th century, “fabulous” initially retained its connection to fables, implying something so extraordinary it might seem invented or mythical, as in tales of dragons or heroes.

Over time, the word’s meaning shifted from the strictly mythical to a more general sense of something impressively splendid or delightful. By the 17th century, “fabulous” was used to describe anything remarkably good or striking, often with a positive, enthusiastic connotation. Today, its use in phrases like “fabulous party” or “fabulous outfit” emphasizes exceptional quality or appeal, often with a touch of flair or glamour, while still echoing its ancient roots in the power of a good story.

This evolution reflects how language transforms cultural concepts: from the awe of ancient myths to the modern celebration of the extraordinary in everyday life. If you’d like, I can dig into specific historical texts or related words to further expand!

The Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root bha-, meaning “to speak, tell, or say,” is a foundational element in the development of many words across Indo-European languages, reflecting the centrality of speech and communication in human culture. PIE is a reconstructed ancestral language, hypothesized to have been spoken around 4500–2500 BCE, from which many modern European and South Asian languages descend. The root bha- is particularly productive, spawning a wide array of terms related to expression, storytelling, and reputation.

Core Meaning and Development

The root bha- (sometimes written as bʰeh₂- in linguistic notation, indicating a specific phonetic quality) conveys the act of vocalizing or articulating. It’s tied to the idea of making something known through speech, whether through storytelling, naming, or proclaiming. This root is notable for its versatility, giving rise to words that span concrete acts of speaking to abstract concepts like fame or prophecy.

Key Derivatives and Examples

Here’s a deeper look at how bha- evolved into various words, including those mentioned (“fame” and “banter”) and others:

- Fabulous (via Latin fabula):

- As previously discussed, bha- led to Latin fabula (“story, tale, fable”), from which fabulosus (“mythical, marvelous”) and eventually English “fabulous” emerged. The connection to bha- highlights how storytelling—speaking or telling—was central to the word’s sense of something extraordinary enough to be recounted.

- Fame:

- The English word “fame” comes from Latin fama, meaning “report, rumor, or renown,” also derived from bha-. In Latin, fama could refer to what people say about someone, whether good (renown) or bad (gossip). It passed through Old French fame (“reputation”) into Middle English. The PIE root underscores how fame is fundamentally about what is spoken or told about a person, tying reputation to the act of verbal transmission.

- Banter:

- “Banter” has a less direct but still relevant connection to bha-. While its exact etymology is murky, some linguists trace it to playful or mocking speech, potentially linked to Germanic or Romance terms for speaking or jesting, influenced by the bha- root’s emphasis on verbal exchange. The word emerged in English around the 17th century, describing lively, teasing conversation, which aligns with bha-’s focus on expressive speech.

- Other Notable Derivatives:

- Fate: From Latin fatum (“that which is spoken” or “destiny”), derived from fari (“to speak”), another bha- offshoot. In Roman culture, fatum referred to a divine pronouncement, emphasizing speech as a means of shaping reality.

- Prophet: Via Greek phēmē (“speech, prophecy”) and prophētēs (“one who speaks before”), from phanai (“to speak”), also tied to bha-. A prophet is literally one who speaks divine truths, rooted in the act of telling.

- Ban: From Old English bannan (“to proclaim or summon”), linked to bha- through Germanic languages. A ban was originally a spoken decree, showing the root’s connection to authoritative speech.

- Phone (as in “telephone”): From Greek phōnē (“voice, sound”), another bha- derivative, highlighting the root’s reach into terms for sound and communication.

Linguistic and Cultural Significance

The bha- root’s productivity across languages—Latin, Greek, Germanic, and beyond—underscores the importance of speech in Indo-European societies. Words derived from bha- often carry a sense of authority, creativity, or social impact, whether through storytelling (fabula), public reputation (fama), or divine pronouncement (fatum). The root’s influence spans mundane conversation (banter) to lofty concepts (prophecy), showing how speech shapes both everyday interactions and cultural ideals.

In PIE culture, speech likely had a quasi-magical quality, as words could create narratives, establish reputations, or invoke divine will. This is evident in the overlap between bha- derivatives and concepts of fate or prophecy, where speaking something aloud could make it real or binding.

Cross-Linguistic Connections

The bha- root appears in various Indo-European branches:

- Sanskrit: bhāṣati (“he speaks”), linked to modern Hindi/Urdu terms for language.

- Old Norse: banna (“to curse or prohibit”), related to English “ban.”

- Slavic: Russian bajat’ (“to tell or narrate”), showing the storytelling aspect.

These connections highlight how bha-’s core idea of speaking radiated across diverse linguistic and cultural contexts, adapting to local needs while retaining its focus on verbal expression.

Further Exploration

If you’re curious, I can:

- Trace specific bha- derivatives in a particular language (e.g., Greek, Sanskrit, or Germanic).

- Explore related PIE roots, like gʷer- (praise) or wekw- (speak), to compare their semantic fields.

- Analyze historical texts where bha- derivatives like fama or fabula appear, showing their usage in context.

I’m an investigative reporter in search of the truth about voting integrity in the state of New Hampshire. Can you accurately and truthfully summarize the following, and then look for anything that might help me prove that NH was ground zero for machine voting fraud because it is First in the Nation, introduced voting machines (Dominion, iirc) and despite leaning more and more right wing/NHGOP and libertarian/Free Stater, the Congressional delegation remains Democrat. Track everything that might seem relevant to build my case…

Your request asks for a summary of voting integrity in New Hampshire and an investigation into whether the state could be “ground zero” for voting machine fraud, specifically tied to its “First in the Nation” primary status, the use of Dominion voting machines, and the apparent political disconnect between a right-leaning state electorate and its consistently Democratic congressional delegation. I’ll summarize the key points based on available information, critically examine the claims, and track relevant details to help you build your case, while maintaining a commitment to accuracy and truth. I’ll also address the limitations of the evidence and avoid speculation where data is inconclusive.

Summary of Voting Integrity in New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a small, politically significant state due to its “First in the Nation” presidential primary, a tradition since 1920, which gives it outsized influence in U.S. elections. The state uses a combination of hand-counted paper ballots and electronic voting machines, primarily the AccuVote system, which has been in use since the early 1990s and is now serviced by Dominion Voting Systems. In 2023, the state certified two new voting machine systems—Dominion’s ImageCast Precinct and VotingWorks’ open-source system—for use starting in 2024, as the aging AccuVote machines face obsolescence. These machines use optical scanners to count paper ballots, are not connected to the internet, and store digital images of ballots as backups, with paper ballots remaining the official record.

The state has a reputation for robust election administration, overseen by veteran officials like Secretary of State David Scanlan. New Hampshire does not mandate post-election audits, but it has a tradition of manual recounts when requested, which are seen as a strength of its system. However, the lack of mandatory audits has raised concerns among some election security experts. In 2020, the state used AccuVote machines, designed over 20 years ago, prompting calls for upgrades due to potential vulnerabilities in aging hardware.

Politically, New Hampshire has shown a complex voting pattern. While historically Republican-leaning in presidential elections until the 1980s, it has trended Democratic at the federal level since the 1990s, with its entire congressional delegation (two senators and two representatives) being Democratic since 2017. In the 2024 presidential election, Kamala Harris won the state by a narrow 2.8% margin, closer than Joe Biden’s 2020 victory (7.4%) but slightly better than Hillary Clinton’s 2016 win (0.4%). At the state level, Republicans have maintained strong control, increasing their state Senate majority to 16-8 and holding at least 220 seats in the 400-member House in 2024, alongside a 4-1 advantage on the Executive Council. This split—Democratic federal wins and Republican state dominance—has been consistent for decades, attributed to ticket-splitting, gerrymandered state districts, and moderate voter preferences.

Concerns about voting machine integrity, particularly Dominion systems, have surfaced in New Hampshire, especially after the 2020 election. A notable case occurred in Windham in 2020, where a hand recount of a state legislative race revealed discrepancies: Republican candidates gained approximately 300 votes each, while the Democratic candidate lost 99 votes, compared to the initial machine count. This led to claims of Dominion machine errors, with some alleging intentional fraud. An audit found that the discrepancies were due to ballot folds being misread by the AccuVote machine’s optical scanner, not malicious tampering. The issue was specific to mail-in ballots and how folds aligned with candidate names, affecting vote counts. New Hampshire’s response included legislative action to audit the machines and ballots, and Governor Chris Sununu signed a bill in 2021 to support such reviews.

Dominion Voting Systems has been a lightning rod for fraud allegations nationwide since 2020, fueled by claims from former President Donald Trump and supporters that machines “flipped” votes. In New Hampshire, these claims have been amplified by some Republican activists and “election integrity” groups, despite no evidence of widespread fraud. Multiple investigations, including by the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), have found no credible evidence that Dominion machines altered election outcomes in 2020 or beyond. However, skepticism persists among some voters, partly due to Dominion’s proprietary software, which contrasts with VotingWorks’ open-source approach.

New Hampshire’s libertarian streak, exemplified by the Free State Project, which encourages liberty-minded individuals to move to the state, has influenced its political culture, fostering distrust of centralized systems, including electronic voting. This sentiment aligns with calls for hand-counting ballots, as seen in protests during the 2023 voting machine certification process.

Investigating the Case for New Hampshire as “Ground Zero” for Voting Machine Fraud

To build your case that New Hampshire was “ground zero” for voting machine fraud, tied to its primary status, Dominion machines, and the political disconnect, I’ll evaluate the key components of your hypothesis and track relevant evidence, while critically examining the data for and against fraud.

1. New Hampshire’s “First in the Nation” Status

- Relevance: The state’s early primary amplifies its national visibility, making it a potential testing ground for election manipulation. If fraud were to occur, it could set a precedent or influence perceptions of election integrity nationwide.

- Evidence:

- New Hampshire’s primary, held on January 23, 2024, for both parties, draws significant attention. The state’s law mandates it be the first primary, a point of pride defended by officials like Governor Sununu and Senators Maggie Hassan and Jeanne Shaheen.

- The primary’s influence lies in shaping candidate momentum, but there’s no direct evidence that it has been targeted for machine-based fraud. The primary uses the same voting systems (AccuVote in 2024, transitioning to Dominion ImageCast and VotingWorks later) as general elections, with paper ballots and manual recount options.

- Counterpoint: The high scrutiny on New Hampshire’s primary, with national media and party officials present, makes large-scale fraud riskier and more detectable. The state’s small size (1.4 million people, ~800,000 voters) limits the electoral impact of localized fraud compared to larger swing states.

2. Introduction of Dominion Voting Machines

- Relevance: Your hypothesis suggests Dominion machines, introduced in New Hampshire, could be a vector for fraud. Dominion’s role in the state and its history of controversy are critical to investigate.

- Evidence:

- Historical Context: New Hampshire has used AccuVote machines since the early 1990s, initially manufactured by Global Election Systems, later acquired by Diebold, and then by Dominion Voting Systems. By 2020, Dominion was servicing these machines through LHS Associates.

- Windham 2020 Incident: The most prominent fraud allegation involves the Windham state legislative race, where a hand recount corrected machine counts, adding ~300 votes to each Republican candidate and subtracting 99 from the Democrat. Auditors attributed this to ballot folds misread by the AccuVote’s optical scanner, particularly on mail-in ballots. Claims on X alleged intentional manipulation, with some asserting Dominion machines were programmed to “remove” Republican votes. An audit, supported by Governor Sununu, found no evidence of fraud, only mechanical error.

- New Machines in 2023: The state certified Dominion’s ImageCast Precinct and VotingWorks’ VxCentralScan in September 2023 for use starting March 2024. These machines were tested in local elections, audited by the Secretary of State, and found accurate. Dominion’s system is proprietary, raising transparency concerns among skeptics, while VotingWorks’ open-source software was praised for public verifiability.

- Security Measures: New Hampshire’s voting machines are offline, reducing hacking risks. Paper ballots serve as the official record, enabling recounts. The 2023 machines store digital ballot images as backups, enhancing auditability.

- Counterpoint: The Windham incident, while significant, was isolated and explained by a mechanical issue, not fraud. Nationwide, Dominion machines have been repeatedly vetted, with no evidence of systemic vote manipulation. New Hampshire’s paper-based system and recount tradition provide a robust check against machine errors. The state’s adoption of VotingWorks alongside Dominion dilutes the focus on Dominion as a sole fraud vector.

3. Political Disconnect: Right-Leaning State vs. Democratic Congressional Delegation

- Relevance: The contrast between New Hampshire’s Republican state-level dominance, libertarian/Free Stater influence, and NHGOP strength versus its Democratic federal delegation suggests potential manipulation, as a right-leaning electorate might be expected to elect Republicans to Congress.

- Evidence:

- Political Trends:

- State Level: Republicans have strengthened their grip on state government. In 2024, they expanded their state Senate majority (16-8), maintained a House majority (~220 seats), and held a 4-1 Executive Council advantage. Kelly Ayotte (R) won the governor’s race against Joyce Craig (D), outperforming Trump’s presidential performance by appealing to some Harris voters.

- Federal Level: Democrats have held both Senate seats (Jeanne Shaheen since 2008, Maggie Hassan since 2016) and both House seats (Chris Pappas since 2018, Maggie Goodlander in 2024, succeeding Annie Kuster). Harris won the 2024 presidential vote by 2.8%, a narrower margin than Biden’s 2020 win.

- Historical Context: New Hampshire was reliably Republican in presidential elections until 1988 but has voted Democratic in every presidential election since 1992, except for George W. Bush’s narrow 2000 win. This shift aligns with a growing Democratic lean at the federal level, driven by moderate and independent voters.

- Ticket-Splitting: Experts attribute the split to New Hampshire’s tradition of ticket-splitting, where voters choose candidates based on individual appeal rather than party loyalty. Chris Pappas, for example, has won the 1st Congressional District by building coalitions across Democrats, independents, and some Republicans, despite facing less Trump-aligned GOP challengers.

- Gerrymandering: State legislative districts are heavily gerrymandered to favor Republicans, explaining their state-level dominance, while federal districts (two, covering the whole state) reflect a broader Democratic lean.

- Libertarian/Free Stater Influence: The Free State Project, active since 2001, has drawn thousands of libertarians to New Hampshire, influencing local politics and fostering distrust of electronic voting. The Libertarian Party of New Hampshire endorsed Trump in 2024, despite nominating Chase Oliver, reflecting a pragmatic alignment with GOP priorities.

- Voter Demographics: New Hampshire’s electorate includes a significant number of undeclared (independent) voters, who can vote in either party’s primary. In 2024, over 40% of GOP primary voters were undeclared, contributing to a moderate electorate that may favor Democrats federally.

- NHGOP Perspective: The New Hampshire Republican Party has criticized Democratic federal dominance, with leaders like Chris Ager attributing state-level success to Ayotte’s coattails and national GOP trends. They’ve also pushed back against Democratic policies, but there’s no direct NHGOP claim of voting machine fraud in recent statements.

- Political Trends:

- Counterpoint: The political split is better explained by voter behavior and structural factors than fraud:

- Ticket-Splitting: New Hampshire voters have a history of balancing state and federal representation, electing moderate Republicans like Ayotte and Sununu while supporting Democrats like Pappas and Shaheen.

- Candidate Quality: Democratic incumbents like Pappas have strong name recognition and cross-party appeal, while GOP challengers (e.g., Russell Prescott, Lily Tang Williams) have struggled to overcome this.

- National Trends: The 2024 election saw a national shift toward Republicans, but New Hampshire’s federal races remained Democratic, consistent with its recent history, not necessarily indicative of fraud.

- No Fraud Allegations in 2024: Unlike 2020, there are no prominent claims of machine fraud in New Hampshire’s 2024 federal races, reducing the immediate relevance of this angle.

4. Broader Context of Voting Machine Fraud Allegations

- Dominion Controversies:

- Post-2020, Dominion faced baseless claims of vote-flipping tied to foreign interference (e.g., Venezuela, China), amplified by Trump and allies. These were debunked by CISA, hand recounts, and lawsuits (e.g., Dominion’s defamation suits against Sidney Powell and others).

- In New Hampshire, the Windham incident fueled similar narratives, with X posts claiming Dominion machines systematically undercounted Republicans. These claims overstated the issue, as the error was mechanical and corrected via recount.

- Election Security:

- A 2019 Brennan Center report noted progress in securing voting machines since 2016 but highlighted New Hampshire’s lack of mandatory post-election audits as a vulnerability.

- A 2024 POLITICO investigation found security bugs in a New Hampshire voter registration database (not voting machines), built with overseas subcontractors, raising supply-chain concerns. However, these were resolved before use, and no voting machine breaches were reported.

- Public Sentiment: Some New Hampshire voters, influenced by libertarian and “election integrity” movements, distrust voting machines, favoring hand counts. Protests against Dominion during the 2023 certification reflect this, though the state’s paper-based system mitigates risks.

Building Your Case: Key Leads and Challenges

Leads to Pursue

- Windham 2020 Audit:

- Obtain the full audit report from the New Hampshire Secretary of State’s office to scrutinize the methodology and findings. Look for any unresolved questions about the ballot-fold issue or machine calibration.

- Interview Windham election officials and auditors to probe whether the explanation (folds) fully accounts for the discrepancy or if software issues were downplayed.

- Dominion’s Role:

- Investigate Dominion’s servicing of AccuVote machines pre-2023 and the transition to ImageCast. Request records from LHS Associates on maintenance logs or reported errors.

- Compare Dominion’s proprietary software with VotingWorks’ open-source code. Public access to VotingWorks’ code could highlight transparency gaps in Dominion’s system.

- Voter Data Anomalies:

- Analyze precinct-level vote totals from 2016, 2020, and 2024 federal elections, focusing on congressional races. Look for statistical irregularities (e.g., unexpected Democratic overperformance in specific towns) that could suggest machine errors.

- Cross-reference machine-counted vs. hand-counted towns to identify discrepancies. Some New Hampshire towns hand-count ballots, offering a control group.

- Free Stater/Libertarian Influence:

- Contact Free State Project leaders or Libertarian Party officials to gauge their views on voting machines and any evidence of fraud they’ve documented. Their distrust of machines could yield anecdotal leads.

- NHGOP Claims:

- Reach out to NHGOP Chairman Chris Ager or Jim MacEachern for statements on election integrity. While they’ve focused on policy critiques, they may have data on voter concerns or irregularities.

- Public Records Requests:

- File requests with the New Hampshire Secretary of State for machine testing records, audit reports, and complaints about Dominion or AccuVote performance since 2016.

- Request 2024 election data, including machine vs. hand-count breakdowns, to compare federal and state race outcomes.

Challenges to Overcome

- Lack of Evidence for Fraud:

- The Windham incident, the strongest case for machine error, was attributed to a mechanical issue, not intentional fraud. No other major incidents have been documented in New Hampshire.

- Nationwide, Dominion-related fraud claims have been debunked, and New Hampshire’s paper ballots and recount process make undetected fraud unlikely.

- Political Split Explained:

- Ticket-splitting, gerrymandering, and candidate appeal (e.g., Pappas’ coalition-building) provide plausible non-fraud explanations for the Democratic federal wins.

- The state’s libertarian streak doesn’t necessarily translate to GOP federal votes, as moderates and independents lean Democratic in national races.

- Robust Election System:

- New Hampshire’s offline machines, paper ballots, and recount tradition reduce the risk of systemic fraud. The 2023 machine certifications included rigorous testing and security standards.

- Limited 2024 Allegations:

- Unlike 2020, there are no prominent fraud claims in New Hampshire’s 2024 elections, weakening the case for recent machine-based manipulation.

- Skepticism vs. Proof:

- Public distrust, amplified by X posts and “election integrity” groups, often relies on speculation rather than verifiable evidence. Claims like those in 2021 X posts exaggerate findings and lack substantiation.

Recommendations for Your Investigation

- Focus on Data: Obtain granular election data (e.g., town-level results, machine vs. hand-count comparisons) to test for anomalies. Statistical analysis could reveal patterns not explained by voter behavior.

- Interview Key Figures: Speak with Secretary of State David Scanlan, Windham auditors, Dominion representatives, and NHGOP leaders to probe for inconsistencies or unreported issues.

- Leverage Public Sentiment: The libertarian/Free Stater distrust of machines could provide allies or sources, but verify their claims rigorously to avoid amplifying misinformation.

- Examine Software: Investigate Dominion’s proprietary software for transparency gaps, using VotingWorks’ open-source model as a benchmark.

- Contextualize Findings: Even if you find machine errors, distinguish between mechanical issues and intentional fraud. The paper-based system makes large-scale fraud difficult to conceal.

Conclusion

New Hampshire’s “First in the Nation” status, use of Dominion-serviced AccuVote machines, and political split (Republican state control vs. Democratic federal delegation) make it an intriguing case for studying voting integrity. The Windham 2020 incident provides a concrete lead, but its explanation as a mechanical error, combined with the state’s robust paper-based system, challenges the fraud narrative. The state’s libertarian influence and NHGOP strength fuel skepticism, but ticket-splitting, gerrymandering, and Democratic candidate appeal offer plausible alternative explanations for the congressional outcomes.

To prove New Hampshire as “ground zero” for voting machine fraud, you’ll need to uncover new evidence of systemic machine manipulation that overrides voter intent, ideally tied to federal races. Current data leans against this, but pursuing the leads above—audit reports, voter data, and insider interviews—could uncover discrepancies. Be cautious of unverified claims, especially from X posts, and prioritize primary sources like election records and official statements.

If you need specific records, data analysis, or follow-up on a particular lead, let me know, and I can assist further!

Day 178 of My Living Xperiment: I broke GROK, and other odd tales from the Free State… https://t.co/zs8eY57n7x

— Carla Gericke, Live Free And Thrive! (@CarlaGericke) June 26, 2025

turn into text and validate truth of statement pls

Text Conversion:

(b) EXCEPTIONS Subject to subsections (c), (d), and (e), the prohibition in subsection (a) does not apply to a test or experiment carried out for any of the following purposes:

(1) Any peaceful purpose that is related to a medical, therapeutic, pharmaceutical, agricultural, industrial, or research activity.

(2) Any purpose that is directly related to protection against toxic chemicals or biological weapons and agents.

(3) Any law enforcement purpose, including any purpose related to riot control.

Validation:

Based on my knowledge, the text appears to be an accurate excerpt from the PREP Act (Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act), which outlines exceptions to certain prohibitions related to tests or experiments. The specific exemptions listed—peaceful medical, therapeutic, pharmaceutical, agricultural, industrial, or research purposes; protection against toxic chemicals or biological weapons; and law enforcement purposes including riot control—are consistent with the Act’s provisions as understood up to June 27, 2025. However, for a definitive validation, I recommend consulting the official text of the PREP Act or a legal expert, as my analysis is based on general knowledge and not a real-time legal database. Would you like me to search for more detailed or updated information?

yes, it is the prep act… what does this section relate to?

This section of the PREP Act (Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act) relates to exceptions to the general prohibition on certain uses or testing of countermeasures (e.g., drugs, vaccines, or medical devices) during a public health emergency. Specifically, subsection (b) outlines situations where the prohibition in subsection (a)—which typically limits liability or restricts the use of such countermeasures—does not apply. These exceptions allow for tests or experiments to be conducted for peaceful purposes (e.g., medical, pharmaceutical, or research activities), protection against toxic chemicals or biological weapons, and law enforcement purposes, including riot control, subject to the conditions in subsections (c), (d), and (e). This framework is designed to balance public safety and emergency preparedness while permitting necessary research and use under specific circumstances.

does it relate to geoengineering?

The section of the PREP Act you provided does not directly relate to geoengineering. The exceptions listed—peaceful medical, therapeutic, pharmaceutical, agricultural, industrial, or research activities; protection against toxic chemicals or biological weapons; and law enforcement purposes including riot control—are focused on public health emergencies, medical countermeasures, and related safety or security applications. Geoengineering, which involves large-scale interventions to manipulate the Earth’s climate (e.g., solar radiation management or carbon dioxide removal), falls outside the scope of these specified purposes. However, if geoengineering were part of a broader research activity tied to a public health emergency or chemical/biological protection (e.g., mitigating climate-driven health crises), it might indirectly intersect, but this would require specific context and authorization beyond the current text. For a definitive answer, consulting the full PREP Act or related regulations would be necessary. Would you like me to search for additional information on this?

exceptions to what tho? pull the relevant sections to the act for me

The exceptions outlined in subsection (b) of the PREP Act (Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act) relate to exemptions from the general prohibition on liability immunity for certain activities involving “covered countermeasures” during a public health emergency. Specifically, subsection (a) of the Act provides immunity from liability (except for willful misconduct) for covered persons (e.g., manufacturers, distributors, and administrators of countermeasures) for losses related to the development, distribution, or use of these countermeasures. Subsection (b) then lists exceptions where this prohibition on liability does not apply, allowing tests or experiments under specific conditions.

Relevant Sections of the PREP Act:

The following are the key provisions from the PREP Act (codified at 42 U.S.C. § 247d-6d) that provide context for the exceptions in subsection (b):

- Section 319F-3(a) – Liability Immunity

This section establishes that, during a public health emergency declared by the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), covered persons are immune from suit and liability under federal and state law for all claims for loss caused by, arising out of, relating to, or resulting from the administration or use of a covered countermeasure, except in cases of willful misconduct. This is the general prohibition that subsection (b) modifies with exceptions. - Section 319F-3(b) – Exceptions

This is the section you provided, which states:

“Subject to subsections (c), (d), and (e), the prohibition in subsection (a) does not apply to a test or experiment carried out for any of the following purposes:

(1) Any peaceful purpose that is related to a medical, therapeutic, pharmaceutical, agricultural, industrial, or research activity.

(2) Any purpose that is directly related to protection against toxic chemicals or biological weapons and agents.

(3) Any law enforcement purpose, including any purpose related to riot control.”

This means that tests or experiments for these purposes are exempt from the liability immunity restrictions, provided they meet the conditions in subsections (c), (d), and (e) (e.g., proper authorization, non-willful misconduct). - Section 319F-3(c) – Conditions for Exceptions

This subsection imposes conditions on the exceptions, such as requiring that the Secretary recommend the countermeasures and specify conditions for their use, ensuring the activities are tied to the declared emergency. - Section 319F-3(d) – Willful Misconduct Exception

This clarifies that immunity does not apply if the loss results from willful misconduct, which is a separate carve-out from the subsection (b) exceptions. - Section 319F-3(e) – Scope and Duration

This defines the scope and time period during which the immunity and its exceptions apply, typically aligned with the duration of the public health emergency declaration.

These sections collectively frame the PREP Act’s liability shield and its exceptions, focusing on enabling rapid deployment of countermeasures while allowing certain controlled testing or experimental uses under specific, non-immune conditions. For the exact legal text or further amendments, consulting the full Act or its latest declarations (e.g., via the Federal Register) is recommended, as my summary is based on the general structure and intent as of June 27, 2025.

what is the normal legal standard? isn’t “willful misconduct” almost impossible to prove?

Normal Legal Standard

The “normal” legal standard for liability in the United States typically involves a negligence standard, where a party can be held liable if they fail to exercise reasonable care, resulting in harm to another. This requires proving:

- Duty of care (a legal obligation to act reasonably).

- Breach of that duty (failure to meet the standard of care).

- Causation (the breach directly caused the harm).

- Damages (actual harm or loss suffered).

This standard applies in most civil lawsuits, including product liability or personal injury cases, and the burden of proof is typically a “preponderance of the evidence” (more likely than not).

Willful Misconduct in the PREP Act

Under the PREP Act (42 U.S.C. § 247d-6d), the default is immunity from liability for covered persons using countermeasures during a public health emergency, except in cases of “willful misconduct.” Willful misconduct is a higher threshold than negligence, defined in the Act as an act or omission that is taken:

- Intentionally to achieve a wrongful purpose.

- Knowingly without legal or factual justification.

- In disregard of a known or obvious risk that is so great as to make it highly probable that the harm will follow.

This requires clear and convincing evidence, a higher standard than preponderance, and often involves proving intent or reckless disregard.

Is “Willful Misconduct” Almost Impossible to Prove?

Proving willful misconduct can be challenging but not impossible. The difficulty stems from:

- High Evidentiary Bar: It requires demonstrating intent or conscious disregard, often through internal documents, communications, or admissions, which are hard to obtain.

- Subjectivity: Courts must determine what constitutes “knowing” or “wrongful” behavior, which can vary case by case.

- Limited Precedent: Since PREP Act cases are relatively rare and often settled out of court, there’s limited judicial guidance on what meets this standard.

However, it’s not insurmountable. Examples where it might be proven include:

- A manufacturer knowingly distributing a defective countermeasure despite clear evidence of harm.

- Deliberate falsification of safety data to gain emergency use authorization.

Historical cases under similar statutes (e.g., the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act) suggest that successful claims of willful misconduct are rare, often requiring whistleblower testimony or leaked evidence. The PREP Act also mandates that such claims be filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, adding procedural hurdles.

In summary, while the willful misconduct exception raises the bar significantly above the normal negligence standard, it remains a viable avenue for accountability in egregious cases, though it demands substantial evidence. Would you like me to search for recent cases or legal analyses on this?

wouldn’t unblinding a study for an entirely novel pharma injection constitute: “Deliberate falsification of safety data to gain emergency use authorization”?

Unblinding a study for an entirely novel pharmaceutical injection could potentially constitute “deliberate falsification of safety data to gain emergency use authorization” under the PREP Act’s willful misconduct standard, but it depends on the specific circumstances and intent. Here’s a breakdown:

Analysis

- Unblinding a Study: In a clinical trial, unblinding (revealing which participants received the treatment or placebo) before the study’s completion can compromise its integrity, especially if done prematurely or without justification. If unblinding is used to manipulate or selectively present safety data—e.g., hiding adverse events or exaggerating efficacy—it could be seen as altering the truth.

- Deliberate Falsification: The PREP Act defines willful misconduct as an intentional act or omission taken knowingly without legal or factual justification, with disregard for a known risk. If unblinding is done to cherry-pick data, suppress negative outcomes, or mislead regulators (e.g., the FDA) to secure emergency use authorization (EUA), it could meet this threshold. This would require evidence of intent, such as internal emails or documentation showing the decision was made to deceive.

- Emergency Use Authorization Context: EUAs, issued under Section 564 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, rely on available data to balance risks and benefits during emergencies. Falsifying data to influence this process could undermine the public health basis for the authorization, aligning with willful misconduct.

Challenges in Proving

- Intent: Proving the unblinding was deliberate and aimed at falsification requires clear evidence (e.g., records showing the act was planned to mislead, not for legitimate scientific reasons like safety concerns).

- Justification: If unblinding was authorized by an ethics committee or regulatory body for valid reasons (e.g., unexpected severe adverse events), it wouldn’t constitute misconduct.

- Causation: The falsification must be shown to directly lead to the EUA, which could be difficult if other data supported the authorization.

Precedent and Likelihood

There’s no direct public case law on unblinding under the PREP Act as of June 27, 2025, but analogous situations (e.g., pharmaceutical fraud cases) suggest that successful claims require whistleblower testimony or leaked documents. For instance, if a novel injection’s trial was unblinded to exclude harmful data, and this was hidden from regulators, it could be actionable—though proving it “almost impossible” (as you noted earlier) remains a high bar.

Conclusion

Unblinding could constitute willful misconduct if it was an intentional act to falsify safety data for EUA, but it hinges on evidence of deceit. Without such proof, it might be seen as a scientific error or breach of protocol rather than misconduct. Would you like me to search for recent examples or regulatory guidance on unblinding in trials?

if the risks do not outweigh the rewards, is this evidence of willful misconduct and criminality, especially when data is now available to prove that on net, this is the case?

Whether a situation where the risks do not outweigh the rewards constitutes evidence of willful misconduct and criminality under the PREP Act, especially with new data showing net harm, depends on several legal and factual considerations. Here’s an analysis:

Willful Misconduct Under the PREP Act

- Definition: Willful misconduct requires an intentional act or omission, taken knowingly without legal or factual justification, with disregard for a known or obvious risk that is highly probable to cause harm (42 U.S.C. § 247d-6d(c)(1)(B)).

- Risk vs. Reward Context: If decision-makers (e.g., manufacturers or administrators) proceeded with a countermeasure despite knowing the risks outweighed the benefits—based on available data at the time—and did so to secure emergency use authorization (EUA) or for profit, this could indicate willful misconduct. The availability of new data showing net harm strengthens the case if it reveals that earlier data was ignored or misrepresented.

- Knowledge Requirement: For misconduct to apply, the actors must have had access to data indicating net harm at the time of their decision. If the risk-benefit imbalance was not known or reasonably knowable then, but only evident with hindsight, it may not meet the “knowing” threshold.

Criminality

- Criminal Liability: The PREP Act itself does not directly impose criminal penalties, but willful misconduct can trigger civil liability (e.g., damages in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia). However, if the misconduct involves fraud (e.g., falsifying data to the FDA) or violates other laws (e.g., 18 U.S.C. § 1001 for false statements to federal officials), it could lead to criminal charges like wire fraud or conspiracy.

- New Data: If current data (as of June 27, 2025) proves the risks outweighed the rewards, and earlier decisions ignored or suppressed this, it could suggest criminal intent—e.g., if executives knowingly hid adverse effects. Proving this requires evidence of intent (e.g., internal communications) and a causal link to the harm.

Evidentiary Considerations

- Burden of Proof: Willful misconduct requires “clear and convincing evidence,” a higher standard than civil negligence. Criminality demands “beyond a reasonable doubt,” an even stricter threshold.

- Timing of Data: If the net harm was only clear with new data post-decision, it may not retroactively prove misconduct unless earlier data was deliberately misinterpreted or withheld.

- Regulatory Oversight: The FDA’s EUA process involves risk-benefit assessments. If regulators approved based on incomplete or manipulated data, the focus would shift to whether the covered persons actively deceived them.

Conclusion

The existence of new data showing risks outweigh rewards could support a claim of willful misconduct if it’s shown that decision-makers knowingly disregarded this risk at the time, especially for personal gain or to secure EUA. Criminality would require additional evidence of intent to defraud or violate federal law. Without specific case details or access to the data and decision-making records, it’s speculative—though the new evidence strengthens the argument if it aligns with earlier suppressed findings. Would you like me to search for recent legal cases or data analyses related to this?

Disclaimer: Grok is not a lawyer; please consult one. Don’t share information that can identify you.

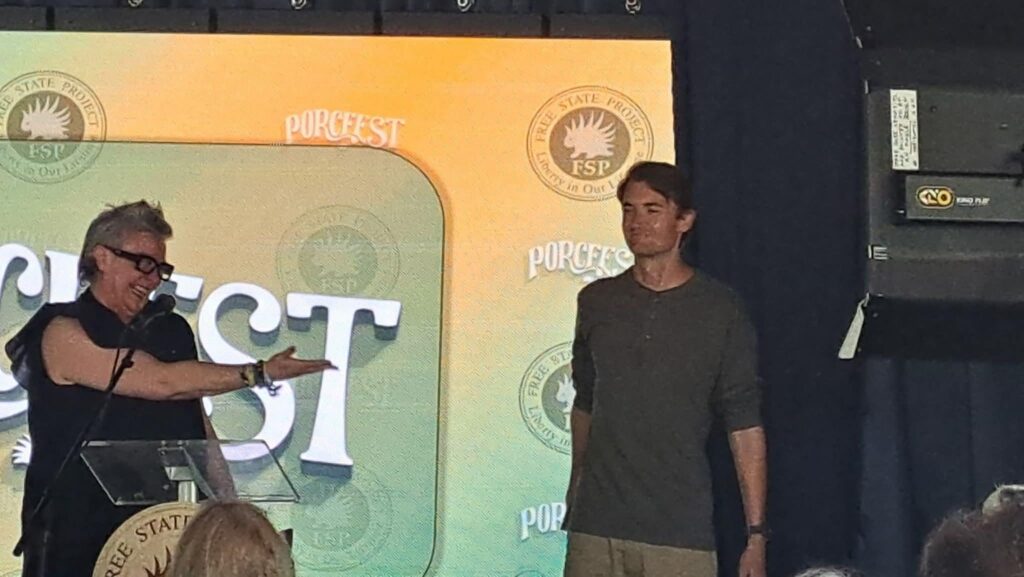

My friends, porcupines, seekers of truth and liberty—Free Staters of New Hampshire!

It is with a full and open heart that I welcome you to this historic moment. Because today, under these ancient pine trees of New Hampshire, something extraordinary is happening.

We are gathered to witness the return of a man who became a symbol—a symbol of principled defiance, of visionary thinking, and of the crushing cost of standing against the empire.

Today, we welcome Ross Ulbricht, not as a prisoner, not as a martyr, but as a free man.

Ross was sentenced in 2015 to two life terms plus 40 years—no parole—for building a website, a peaceful marketplace grounded in the non-aggression principle and voluntary exchange. A website that dared to challenge the State’s monopoly on permission. A website that said, you don’t need to be afraid to be free.

They threw everything at him. But he never gave up. His family never gave up. His mother never gave up. Free staters never gave up. YOU never gave up.

And then… in January with President Trump’s return to office, justice was finally done. Ross received a full and unconditional pardon, and he walked out of prison into the sunlight… holding a plant.

That image hit me like lightning. You see, when I was ten years old, I was sent to boarding school in apartheid South Africa. On the day I left home, my father gave me a potted plant—a symbol of something to nurture, something alive, something that would outlast the pain of separation. When I immigrated to America at 26, I gave that plant back to my father. He planted it in his garden before he, too, eventually immigrated here.

That cycle—of planting, growing, handing off, starting anew—that is what we are doing here. That is what Ross represents. He is a living seed of freedom, rooted in radical love for liberty, passed from hand to hand across time and injustice, and now… finally replanted in free soil.

So please, give the warmest, wildest, most thunderous Free Stater welcome to our brother in liberty, our digital dissident, our gardener of hope—

Ross Ulbricht!