Whatta thrill today when I went to open the back of my new car to release Obi at the trailhead, and saw my vanity license plate for the first time.

The word “fabulous” has a delightfully rich history, rooted in storytelling and wonder. Here’s a breakdown:

🔤 Etymology of “Fabulous”

- Origin: Latin

- Latin Root: fabulosus

- From fabula = “story, fable, narrative”

- Fabula itself comes from fari = “to speak, tell”

So, originally, fabulosus meant something like “pertaining to stories or fables” — things that are imaginary, legendary, or unbelievable.

📚 Evolution in English

- Late Middle English (1400s):

“Fabulous” enters English meaning “mythical, legendary, related to fables”, i.e., not real, fantastical. - 1600s onward:

The meaning starts to stretch toward the extraordinary or hard to believe, e.g., “fabulous wealth.” - Mid-20th Century (especially in American English):

The word gets a slang upgrade to mean “extremely good,” “wonderful,” “stylish,” or “amazing” — think Hollywood glamour, fashion, or a diva’s compliment.

✨ Modern Usage

Today, “fabulous” can mean:

- Fictional or mythological (e.g., “fabulous beasts”)

- Extremely good or impressive (e.g., “That dress is fabulous!”)

- Used in queer and drag culture as a campy superlative (e.g., “You look absolutely fabulous, darling!”)

🧠 Related Words

- Fable: a short story with a moral

- Fabulist: someone who tells fables — or lies

- Fiction: a cousin in the world of the imagined

🌈 TL;DR

“Fabulous” started as a word about fables and fantasy, and morphed into a celebration of things so good, they feel almost unreal. It’s a word that straddles imagination and admiration — a sparkle from Latin lore to modern slang.

more along these lines: It’s a word that straddles imagination and admiration… give me some references from art

Absolutely. “Fabulous” is one of those words that shimmers with double meaning—rooted in fable (myth, magic, storytelling) and now used for style, excess, glamor, awe. It stands at the crossroads of imagination and admiration, as you said. Below are some rich artistic and cultural references that show how “fabulous” has straddled those worlds:

🎭 Classical Art & Myth

- “Fabulous beasts” in medieval manuscripts and ancient mythologies:

These are not just imaginary animals (griffins, unicorns, chimeras), but symbols of moral or cosmic truth. The term fabulous here means both unreal and extra-significant.- See: Bestiaries of the Middle Ages

- Dürer’s Rhinoceros (1515), which was drawn based on a description, not direct observation—a fabulous rendering of a real creature.

- Ovid’s Metamorphoses:

A fountainhead of fabulous stories—gods transforming mortals, men becoming stars, lovers turned into trees. The fabulous here is the transformative power of story.

💃 Baroque & Rococo Excess

- The 17th and 18th centuries leaned into the fabulous—extravagant, theatrical, dripping with gold and silk. Think:

- Versailles: Louis XIV didn’t just build a palace, he built a fabulous fantasy of divine right and celestial glory.

- Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Swing (1767): flirtation, lushness, mythic gardens—delight made visual.

✨ Fashion and Glamour

- Elsa Schiaparelli, surrealist fashion designer:

Her work with Dalí (lobster dresses, shoe hats) is literally fabulous—unreal, dreamlike, admired. She once said, “In difficult times, fashion is always outrageous.”

→ That outrageousness became synonymous with fabulousness. - Studio 54 Era (1970s):

The word fabulous became cultural currency.- Think Andy Warhol, Grace Jones, Halston, Bianca Jagger on a white horse—all embodiments of fabulous as elevated mythmaking in real life.

🏳️🌈 Queer Culture & Drag

- Fabulous became a form of identity armor and self-expression—owning one’s difference and daring to shine.

- RuPaul: “You’re born naked and the rest is drag.” Every layer after that? A fabulous invention.

- In this context, “fabulous” reclaims the fantastical, turning it into a power move. Not fake—fierce.

🖼️ Modern & Contemporary Art

- Jeff Koons’ balloon animals and Takashi Murakami’s psychedelic color explosions live in the land of fabulous—glossy, surreal, high and low all at once.

- Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Rooms are literally fabulous: step inside and leave the real world behind.

🧵 In Sum:

Fabulous is a thread that runs through:

- The unreal and the ideal,

- The imaginary and the iconic,

- The fable and the famous.

It’s not just about fantasy—it’s about elevation, adornment, awe. It’s what happens when storytelling puts on heels and struts into the spotlight.

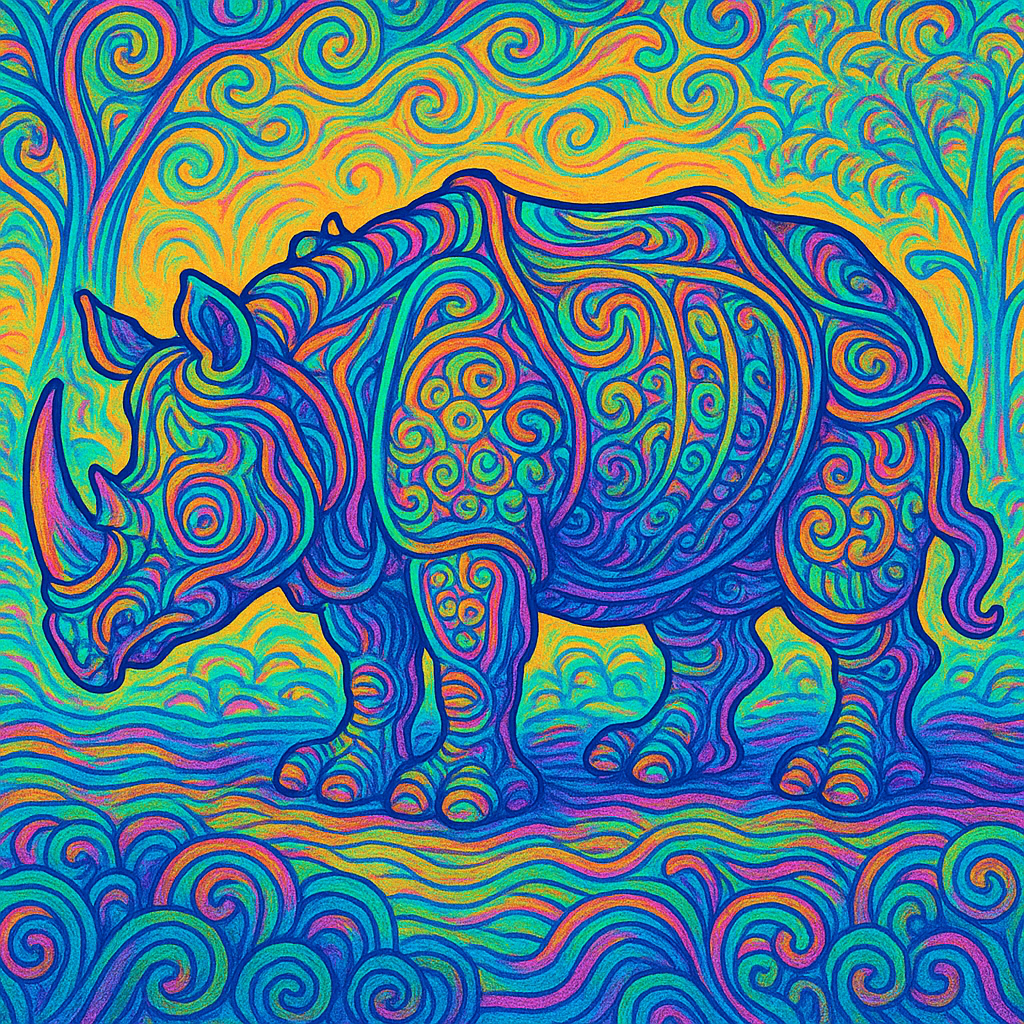

Dürer’s Rhinoceros (1515) show me

Here is Albrecht Dürer’s famous Rhinoceros (1515) – one of the most iconic “fabulous” creatures in Western art:

🐘 About the Image:

- Dürer never saw a rhinoceros in real life.

- He based this woodcut on a written description and a sketch by someone who had seen it in Lisbon, where the first rhino in Europe in over 1,000 years had arrived.

- The result? An animal with armor-like plates, decorative rivets, and an extra horn on its back—a fabulous creature, part real, part myth.

Why It Matters:

This rhinoceros was treated like a marvel, a beast of wonder, a symbol of power and the exotic. Even though it’s inaccurate, the image was so compelling it became the standard European depiction of a rhino for centuries.

It’s the perfect example of “fabulous” in its original sense: mythologized, exaggerated, and beloved for its audacity.

What does fabulous mean, GROK?

“Fabulous” means extraordinary, especially extraordinarily large or impressive; wonderful or marvelous. It can describe something or someone exceptionally good, pleasing, or striking, often with a sense of enthusiasm or flair. For example, “She looked fabulous in her new dress” or “The party was absolutely fabulous!” It’s rooted in the word “fable,” implying something almost mythical in its greatness.

The etymology of “fabulous” is quite rich, reflecting its journey from ancient storytelling to modern exuberance. The word originates from the Latin fabulosus, which means “celebrated in fables” or “mythical.” This derives from fabula, meaning “story,” “tale,” or “fable,” often carrying a sense of something legendary or extraordinary. Fabula itself stems from the Proto-Indo-European root bha-, which means “to speak, tell, or say,” a root that also underpins words like “fame” and “banter.”

In its early Latin usage, fabulosus was tied to the realm of myth and narrative, describing things so grand or fantastical they belonged in stories. By the time it reached Old French as fableux (around the 13th century), it began to take on a broader sense of “marvelous” or “wonderful.” When it entered Middle English in the 15th century, “fabulous” initially retained its connection to fables, implying something so extraordinary it might seem invented or mythical, as in tales of dragons or heroes.

Over time, the word’s meaning shifted from the strictly mythical to a more general sense of something impressively splendid or delightful. By the 17th century, “fabulous” was used to describe anything remarkably good or striking, often with a positive, enthusiastic connotation. Today, its use in phrases like “fabulous party” or “fabulous outfit” emphasizes exceptional quality or appeal, often with a touch of flair or glamour, while still echoing its ancient roots in the power of a good story.

This evolution reflects how language transforms cultural concepts: from the awe of ancient myths to the modern celebration of the extraordinary in everyday life. If you’d like, I can dig into specific historical texts or related words to further expand!

The Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root bha-, meaning “to speak, tell, or say,” is a foundational element in the development of many words across Indo-European languages, reflecting the centrality of speech and communication in human culture. PIE is a reconstructed ancestral language, hypothesized to have been spoken around 4500–2500 BCE, from which many modern European and South Asian languages descend. The root bha- is particularly productive, spawning a wide array of terms related to expression, storytelling, and reputation.

Core Meaning and Development

The root bha- (sometimes written as bʰeh₂- in linguistic notation, indicating a specific phonetic quality) conveys the act of vocalizing or articulating. It’s tied to the idea of making something known through speech, whether through storytelling, naming, or proclaiming. This root is notable for its versatility, giving rise to words that span concrete acts of speaking to abstract concepts like fame or prophecy.

Key Derivatives and Examples

Here’s a deeper look at how bha- evolved into various words, including those mentioned (“fame” and “banter”) and others:

- Fabulous (via Latin fabula):

- As previously discussed, bha- led to Latin fabula (“story, tale, fable”), from which fabulosus (“mythical, marvelous”) and eventually English “fabulous” emerged. The connection to bha- highlights how storytelling—speaking or telling—was central to the word’s sense of something extraordinary enough to be recounted.

- Fame:

- The English word “fame” comes from Latin fama, meaning “report, rumor, or renown,” also derived from bha-. In Latin, fama could refer to what people say about someone, whether good (renown) or bad (gossip). It passed through Old French fame (“reputation”) into Middle English. The PIE root underscores how fame is fundamentally about what is spoken or told about a person, tying reputation to the act of verbal transmission.

- Banter:

- “Banter” has a less direct but still relevant connection to bha-. While its exact etymology is murky, some linguists trace it to playful or mocking speech, potentially linked to Germanic or Romance terms for speaking or jesting, influenced by the bha- root’s emphasis on verbal exchange. The word emerged in English around the 17th century, describing lively, teasing conversation, which aligns with bha-’s focus on expressive speech.

- Other Notable Derivatives:

- Fate: From Latin fatum (“that which is spoken” or “destiny”), derived from fari (“to speak”), another bha- offshoot. In Roman culture, fatum referred to a divine pronouncement, emphasizing speech as a means of shaping reality.

- Prophet: Via Greek phēmē (“speech, prophecy”) and prophētēs (“one who speaks before”), from phanai (“to speak”), also tied to bha-. A prophet is literally one who speaks divine truths, rooted in the act of telling.

- Ban: From Old English bannan (“to proclaim or summon”), linked to bha- through Germanic languages. A ban was originally a spoken decree, showing the root’s connection to authoritative speech.

- Phone (as in “telephone”): From Greek phōnē (“voice, sound”), another bha- derivative, highlighting the root’s reach into terms for sound and communication.

Linguistic and Cultural Significance

The bha- root’s productivity across languages—Latin, Greek, Germanic, and beyond—underscores the importance of speech in Indo-European societies. Words derived from bha- often carry a sense of authority, creativity, or social impact, whether through storytelling (fabula), public reputation (fama), or divine pronouncement (fatum). The root’s influence spans mundane conversation (banter) to lofty concepts (prophecy), showing how speech shapes both everyday interactions and cultural ideals.

In PIE culture, speech likely had a quasi-magical quality, as words could create narratives, establish reputations, or invoke divine will. This is evident in the overlap between bha- derivatives and concepts of fate or prophecy, where speaking something aloud could make it real or binding.

Cross-Linguistic Connections

The bha- root appears in various Indo-European branches:

- Sanskrit: bhāṣati (“he speaks”), linked to modern Hindi/Urdu terms for language.

- Old Norse: banna (“to curse or prohibit”), related to English “ban.”

- Slavic: Russian bajat’ (“to tell or narrate”), showing the storytelling aspect.

These connections highlight how bha-’s core idea of speaking radiated across diverse linguistic and cultural contexts, adapting to local needs while retaining its focus on verbal expression.

Further Exploration

If you’re curious, I can:

- Trace specific bha- derivatives in a particular language (e.g., Greek, Sanskrit, or Germanic).

- Explore related PIE roots, like gʷer- (praise) or wekw- (speak), to compare their semantic fields.

- Analyze historical texts where bha- derivatives like fama or fabula appear, showing their usage in context.