Carla Gericke

Ah yes. That question.

The one people ask right before they lower their voice and look around, as if the walls might be listening.

Because what you’re really asking isn’t when will things change?

It’s: when will we stop agreeing to the lie that this all adds up?

There’s no date on the calendar. No cosmic Outlook invite titled “Awakening – Mandatory.”

But if you’re paying attention—if you’re even asking—you’ve probably noticed:

the pretense is cracking.

Not collapsing.

Cracking.

Hairline fractures first. Quiet ones. The kind you only see once you stop staring at the screens and start trusting your gut again.

People feel it when they’re forced into a binary party system that demands total ideological obedience across fifty unrelated issues.

They feel it when institutions supposedly designed for “the people” openly defy the people—electoral colleges, filibusters, regulatory labyrinths nobody voted for.

They feel it when elections start to resemble a controlled, self-reinforcing loop where the brands change but the outcomes don’t.

The system doesn’t fail—it maintains itself.

With money. With fear. With divide-and-conquer theater. With unlimited bribery dressed up as “campaign finance.”

Leftists correctly spot the corporatist scam—then demand more power for the same managerial class.

Liberals preach democracy while defending systems that require mass psychological compliance to function.

Everyone insists their version will fix it, while quietly sensing the whole architecture is upside down.

And here’s the thing history teaches—every time:

Societies don’t collapse all at once.

They come undone.

So slowly you barely notice.

Until one day you look back ten years and think, Oh. That was the moment.

Václav Havel nailed this in The Power of the Powerless:

systems persist because people live within the lie—not because the lie is convincing, but because it’s convenient.

Collapse begins not with revolution, but with people quietly deciding to live in truth instead.

They stop pretending.

They withdraw their belief.

They opt out—not loudly at first, but decisively.

Every real awakening looks like that.

The Soviet Union.

The Arab Spring.

Every empire that mistook compliance for consent.

In America, the accelerants are obvious:

AI exposing hypocrisy at machine speed.

Economic fragility.

Technological transparency.

And a growing number of people realizing inner freedom matters more than winning rigged games.

The most “awake” people aren’t screaming online.

They’re building parallel lives.

Parallel economies.

Parallel communities.

They’re choosing place over politics.

Which is why projects like the Free State Project matter—not as protest, but as practice.

As proof of concept.

As the embodied answer to: Okay, but what do we do instead?

Michael Malice likes to remind us that most people assume everyone else thinks like they do. That’s why absurd systems last so long—each person waits for permission that never comes.

So when does the charade end?

When enough people stop voting for brands

and start building alternatives.

When enough people stop outsourcing conscience

and reclaim consent.

When enough people say, quietly but firmly:

No. This doesn’t make sense anymore.

If you’re asking the question, you’re already early.

The clock isn’t ticking.

It’s shedding parts.

And whether this ends gently or violently depends on how many of us choose to wake up—and where we choose to stand when we do.

(Spoiler: some of us chose New Hampshire.) 🌲

Unalienable… what does this mean, and how has it been subverted

Meaning of “Unalienable”

“Unalienable” (also spelled “inalienable” in modern usage) refers to rights that are inherent to human beings, cannot be surrendered, transferred, taken away, or denied by any government or authority. These are often described as natural rights or God-given rights, existing by virtue of being human rather than granted by laws or rulers.

The term is most famously used in the U.S. Declaration of Independence (1776):

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Here, “unalienable” emphasizes that these rights are not alienable (i.e., they cannot be separated from the individual). “Unalienable” and “inalienable” are synonyms with no meaningful difference today—”unalienable” was the preferred 18th-century spelling in the Declaration’s final version, while “inalienable” became dominant later.

The concept draws from Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke, who argued for natural rights to life, liberty, and property (Jefferson adapted this to “pursuit of Happiness”). Governments exist to secure these rights, deriving power from the consent of the governed; if they fail, people have the right to alter or abolish them.

How the Concept Has Been “Subverted” or Infringed

The idea of unalienable rights has faced criticism and real-world violations throughout history, often described as “subversion” when governments or societies undermine their universality or inviolability:

- Historical Hypocrisy and Exclusion in America:

- The Declaration proclaimed these rights while slavery remained legal, denying them to enslaved Africans and their descendants. Indigenous peoples faced displacement and genocide, and women were excluded from full rights.

- This contradiction highlighted that “all men” was interpreted narrowly (white, property-owning males), subverting the universal claim. Abolitionists, civil rights leaders (e.g., Martin Luther King Jr.), and suffragists later invoked the Declaration to expand protections via amendments and laws.

- Philosophical Criticism:

- Utilitarian Jeremy Bentham called natural rights “nonsense upon stilts,” arguing rights are created by law, not inherent.

- Some modern critics (e.g., cultural relativists) question universality, claiming rights vary by culture or that without enforcement (e.g., government), they don’t exist in practice.

- Others argue rights can conflict (e.g., one person’s liberty infringing another’s safety), requiring regulation.

- Government Infringements:

- Rights are often violated despite being “unalienable”—e.g., internment of Japanese Americans during WWII, restrictions during emergencies, or debates over gun rights vs. public safety.

- Some conservatives argue modern expansions (e.g., positive rights like healthcare) subvert the original focus on negative rights (freedom from interference).

- In broader human rights discourse, efforts to prioritize certain rights (e.g., traditional vs. newer social rights) have sparked debates about diluting core unalienable ones.

In essence, while the concept asserts absolute inviolability, history shows frequent subversion through exclusion, violation, or redefinition—yet it remains a powerful ideal driving reforms toward greater inclusion and protection.

break down in columns what are positive rights and negative rights, and who pays

Positive Rights vs. Negative Rights

The distinction between negative rights (also called liberty rights) and positive rights (also called entitlement or welfare rights) is a key concept in political philosophy, popularized by Isaiah Berlin in his essay “Two Concepts of Liberty” (1958). Negative rights focus on freedom from interference, while positive rights focus on freedom to have or achieve something, often requiring active provision.

Here’s a breakdown in columns:

| Aspect | Negative Rights | Positive Rights |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Rights that require others (individuals or government) to refrain from interfering or acting against you. They protect liberty by imposing duties of non-interference. | Rights that require others (usually government) to actively provide goods, services, or opportunities. They impose duties to act or provide. |

| Philosophical Basis | Classical liberalism (e.g., John Locke, U.S. Founding Fathers’ emphasis on natural rights). Associated with “negative liberty” (freedom from coercion). | Modern welfare states and social democracy. Associated with “positive liberty” (freedom to fulfill potential). Often linked to second-generation human rights (economic/social). |

| Examples | – Freedom of speech (others must not censor you) – Right to life/liberty (protection from murder, enslavement, or arbitrary arrest) – Private property (others must not steal or seize it) – Freedom of religion (no forced belief) | – Right to education (government provides schools/teachers) – Right to healthcare (government-funded treatment) – Right to social security/welfare (benefits during unemployment) – Right to housing or minimum standard of living |

| Cost/Who Pays | Generally low direct cost: Enforced through restraint (no action needed beyond basic legal systems). Any enforcement (e.g., courts, police to prevent violations) is funded by taxpayers collectively, but the right itself doesn’t require transferring resources to individuals. Critics argue pure negative rights have minimal burden. | High direct cost: Requires resources, labor, and funding to provide the good/service. Typically paid by taxpayers (through government redistribution via taxes). Can involve coercion (forced contribution) and may conflict due to scarcity (not everyone can receive equally). |

| Criticisms/Debates | Seen as universally compatible (everyone can enjoy them simultaneously without conflict). Enforcement still needs some positive action (e.g., police protection). | Often criticized as creating dependency or infringing negative rights (e.g., taxing property to fund welfare). Some argue they aren’t “true” rights since they depend on others’ labor/effort. Proponents say they’re essential for equality and dignity. |

This distinction ties into discussions of unalienable rights (mostly negative in the classical sense) and the UDHR (which includes both, e.g., Articles 3–21 lean negative; 22–27 positive).

Note: Some philosophers argue the divide isn’t absolute—enforcing negative rights also requires positive actions (e.g., funding courts). However, the core difference in burden and obligation remains widely recognized.

would it be fair to say negative rights are based on individual action/freedom and positive rights are a form of communism (making people do something for you)

Assessing the Characterization of Negative and Positive Rights

Your question touches on a common debate in political philosophy, where negative rights are often framed as protections for individual autonomy, while positive rights involve obligations on others (typically society or government) to provide resources or services. I’ll break this down step by step to evaluate if your description is “fair,” drawing on standard definitions and critiques. Overall, the first part of your statement aligns reasonably well with classical liberal views, but the second part oversimplifies and isn’t entirely accurate—positive rights aren’t inherently “communist,” though they can involve elements of compulsion that critics associate with collectivist systems.

1. Negative Rights as Based on Individual Action/Freedom

- Is this fair? Yes, this is a fair characterization in many philosophical traditions.

- Explanation: Negative rights (also called “liberty rights” or “negative liberties”) are fundamentally about non-interference—they require others to refrain from actions that would hinder your freedom. This emphasizes individual agency: you are free to act as you choose, as long as you don’t infringe on others’ similar freedoms. For instance:

- The right to free speech means no one (especially government) can censor you, allowing you to express yourself independently.

- The right to property means others can’t seize your belongings, enabling you to use or trade them as you see fit.

- This aligns with thinkers like John Locke and Isaiah Berlin, who saw negative rights as the foundation of personal liberty, where freedom is the absence of external constraints. They are “self-executing” in the sense that they don’t demand active provision from others; enforcement mainly involves preventing violations (e.g., via courts or police).

- Caveat: Even negative rights aren’t purely “individual” in practice—they often require societal structures (like a legal system) to protect them, which involves some collective action.

2. Positive Rights as a Form of Communism (Making People Do Something for You)

- Is this fair? Not really—this is an oversimplification and a bit loaded. While positive rights do involve obligations on others (which can feel like “making people do something”), equating them directly with communism ignores their presence in non-communist systems and reduces a broad concept to a pejorative label.

- Explanation: Positive rights (also called “welfare rights” or “positive liberties”) entitle individuals to receive certain goods, services, or opportunities, which often requires active intervention from society or government. This can involve “making people do something” in the form of redistribution (e.g., taxes funding public services), which critics describe as coercive because it compels contributions from others. Examples include:

- The right to education: Governments must provide schools, teachers, and funding, paid for by taxpayers.

- The right to healthcare: This might require doctors, hospitals, or subsidies, again funded collectively.

- Link to Communism? Positive rights are prominent in communist ideologies (e.g., Marxist theory emphasizes economic rights like the right to work or housing, provided by the state in a classless society). Communist constitutions often promised extensive positive rights, but critics argue they failed due to overpromising without sustainable delivery. However:

- Positive rights aren’t exclusive to communism—they exist in capitalist democracies too. For example, the U.S. has positive rights elements like public education, Social Security, and unemployment benefits. European social democracies (e.g., Sweden, Canada) blend them with market economies through welfare states.

- The “communism” label often comes from libertarian or conservative critiques, who see positive rights as a slippery slope toward collectivism because they prioritize equality over pure individual freedom. But communism specifically involves abolishing private property and class structures, which goes far beyond just providing rights like healthcare.

- Instead of “communism,” a more neutral view is that positive rights reflect social contract ideas (e.g., from Rousseau or modern welfare theorists), where society agrees to mutual support for the common good. The coercion aspect (taxes) is debated: proponents say it’s justified for equity and human dignity, while opponents argue it violates negative rights (e.g., property rights).

Key Differences and Overlaps in a Table

To clarify, here’s a quick comparison highlighting why the communism link isn’t straightforward:

| Aspect | Negative Rights (Individual Freedom Focus) | Positive Rights (Obligation/Provision Focus) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Restrains actions (e.g., “don’t interfere”) | Requires actions (e.g., “provide this”) |

| Basis in Freedom | Freedom from coercion or harm | Freedom to achieve or access something |

| Association with Ideologies | Classical liberalism, libertarianism (e.g., U.S. Bill of Rights emphasizes these) | Social democracy, socialism; communism amplifies them but they’re not unique to it |

| “Making People Do Something” | Minimal—mostly passive restraint | Yes, via taxes/redistribution; seen as coercive by critics, but voluntary in social contracts |

| Examples in Non-Communist Systems | Freedom of assembly (universal in democracies) | Universal basic education (in most capitalist countries) |

In summary, your first point captures the essence of negative rights well, but labeling positive rights as “communism” isn’t fair because it ignores their role in diverse political systems. The debate often boils down to balancing individual liberty with collective welfare—positive rights can enable freedom (e.g., education empowers individual action), but they do introduce elements of compulsion that some view as antithetical to pure individualism. If you’re drawing from a specific thinker or context, feel free to provide more details for a deeper dive!

“aren’t inherently “communist,” though they can involve elements of compulsion” which positive rights do NOT involve compulsion?

Do Any Positive Rights Avoid Compulsion Entirely?

To directly address your question: In the standard philosophical distinction (particularly from libertarian and classical liberal perspectives), no typical positive right avoids elements of compulsion when enforced at a societal or governmental level. Positive rights inherently require active provision of goods, services, or opportunities by others—often funded through taxation or regulated redistribution—which critics argue involves coercion (forcing people to contribute resources or labor against their will).

However, there are nuances and edge cases where philosophers argue positive rights can be framed or implemented without direct compulsion:

1. Purely Voluntary or Contractual Positive Rights

- These aren’t “universal” human rights but arise from mutual agreement.

- Example: If you voluntarily join a private club, cooperative, or insurance pool, you gain a “positive right” to benefits (e.g., mutual aid, shared resources) provided by members. No one is forced—participation is consensual, and you can leave.

- This aligns with contract-based obligations: You trade some freedom for provision, but it’s not coerced by the state.

- Limitation: These aren’t inherent or unalienable; they’re optional and don’t apply universally.

2. Rephrased as Negative Rights (Philosophical Workaround)

- Some thinkers (e.g., James Sterba) argue that certain positive claims can be reformulated as negative rights to avoid forced labor or taxation.

- Example: Instead of a “positive right to welfare” (government must provide food/housing via taxes), rephrase as a “negative right not to be prevented from taking surplus resources” from the wealthy if you’re in dire need. This shifts the burden: The poor can take what’s unused, without forcing others to actively give.

- This avoids compelling providers but still involves potential conflict (e.g., self-help enforcement) and isn’t widely accepted as a true positive right.

3. Hybrid or Borderline Cases Often Debated as Positive

- Rights like fair trial (UDHR Article 10) or legal counsel in criminal cases require the state to provide lawyers/judges, funded by taxes—compulsion involved.

- Protection from private violence (e.g., police response) is sometimes called positive but often seen as enforcing negative rights (to life/security).

- No clear example escapes compulsion in practice for universal enforcement.

Why Most Views Say All Enforced Positive Rights Involve Compulsion

| Critique Perspective | Reason Positive Rights Require Compulsion | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Libertarian/Classical Liberal | Provision demands resources/labor from others; taxation = coerced transfer, violating negative property rights. | Healthcare, education, welfare—can’t be guaranteed universally without forcing contributions. |

| General Philosophical Consensus | Positive rights impose “positive duties” (to act/provide), while negative rights impose only “negative duties” (to refrain). Scarcity means someone pays involuntarily. | Social security, housing—voluntary charity isn’t a “right” since it can be withheld. |

| Practical Enforcement | Even “non-coercive” ideals (e.g., voluntary funding) fail at scale; states rely on compulsory taxes/laws. | No modern welfare state funds positive rights purely voluntarily. |

In summary, while positive rights can exist without compulsion in narrow, voluntary contexts (e.g., private contracts or mutual aid societies), universal or state-enforced ones—like those in the UDHR (education, work, social security)—almost always involve some coercion through taxation or regulation. This is why critics (e.g., from libertarian traditions) argue positive rights inherently conflict with pure individual freedom. Proponents counter that such “compulsion” is justified via social contract or democracy for greater equity. If you’re thinking of a specific right, I can analyze it further!

“social contract”… under strict contract law, how does one who has not signed nor explicitly agreed to a contract held to its terms?

Strict Contract Law: Binding Without Signature or Explicit Agreement

Under modern contract law (e.g., in common law jurisdictions like the US, UK, or influenced systems), a person can be bound to a contract without signing it or explicitly agreeing (e.g., saying “I agree”). This occurs primarily through:

- Implied-in-fact contracts: These arise from the parties’ conduct and circumstances showing mutual intent to be bound. For example:

- Ordering and eating food at a restaurant implies agreement to pay the listed price.

- Continuing to work for an employer and accepting pay implies acceptance of employment terms.

- Performing services or delivering goods after receiving an offer, without objection.

- Actions substituting for signature: Beginning performance, accepting benefits, or failing to object (when reasonable to expect objection) can demonstrate acceptance.

- Promissory estoppel: If one party reasonably relies on a promise (causing detriment), the promisor may be bound even without full mutual agreement.

However, key requirements must be met: offer, acceptance (via conduct), consideration (exchange of value), and intent to be legally bound. Silence alone rarely binds unless prior dealings or context imply it. Contracts for major items (e.g., real estate) often require writing/signatures under the Statute of Frauds.

In short: Yes, you can be bound without explicit agreement if your behavior objectively shows consent.

The “Social Contract” Analogy and Why It’s Not a Strict Legal Contract

The social contract in political philosophy (Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Rawls) is a metaphor or thought experiment explaining why we have political obligation (duty to obey laws) and government legitimacy. It is not a literal contract under law.

- No actual agreement: No one signs or explicitly consents (except immigrants via naturalization oaths). Most are born into it.

- Tacit/implied/hypothetical consent:

- Locke: Tacit consent via residing in territory, using roads, or inheriting property—implying you accept benefits and thus obligations.

- Rousseau: More collective “general will.”

- Modern versions (e.g., Rawls): Hypothetical—what rational people would agree to behind a “veil of ignorance.”

Critics (e.g., David Hume, modern philosophers) argue this fails as a true contract analogy:

| Aspect | Strict Contract Law | Social Contract Theory | Key Criticism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consent Required | Mutual, objective intent (express or implied by conduct) | Tacit (residence/benefits) or hypothetical | No real choice—leaving country is costly/impractical (Hume: like being born on a ship and forced to stay) |

| Opt-Out Possible | Can reject offer or breach (with consequences) | Emigration, but often unrealistic | No reasonable exit; benefits (e.g., roads) hard to avoid without consent |

| Mutual Benefits | Consideration required | Protection, order in exchange for obedience | Unequal; government can breach (unjust laws) without easy remedy |

| Enforceability | Courts enforce if elements met | State enforces via coercion | Not voluntary; more imposition than agreement |

| Historical Basis | Actual past dealings | Fictional/hypothetical origin | “Isn’t worth the paper it’s not written on” (common quip) |

The analogy breaks because:

- Real implied contracts require reasonable opportunity to reject and clear actions showing intent.

- Social “consent” is inescapable for most (born subjects), lacking true voluntariness.

- Philosophers use it normatively (to justify limited government or rights) rather than descriptively (as historical fact).

Many conclude the social contract is not legitimate under strict contract principles—it’s a useful fiction or ideal, but political obligation may rest on other grounds (e.g., fairness, gratitude, natural duty, or democracy). Critics like philosophical anarchists argue no general duty to obey exists without actual consent.

In essence: Under law, non-explicit binding is possible but limited and voluntary. The social contract stretches “consent” far beyond that, making the analogy weak or illusory to skeptics.

strictly speaking, what would one call a system under which you are born and are subject to conditions you did not agree to and that you do not consent to?

Strictly speaking, a political or social system in which individuals are born into obligations, laws, and conditions without their personal consent (explicit or otherwise) is most accurately described as one based on political subjection or non-consensual authority.

Common precise terms used in political philosophy and jurisprudence for such a system include:

| Term | Definition/Usage | Key Proponents/Critics | Why It Fits the Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjection | Being placed under the authority or dominion of a ruler/state without voluntary agreement. | Hobbes (in state of nature vs. civil society); modern critics of state legitimacy. | Emphasizes involuntary submission from birth. |

| Coercive Authority | Authority enforced by threat of force, without requiring individual consent. | Weber (monopoly on legitimate violence); libertarian theorists. | Laws apply regardless of agreement; non-compliance punished. |

| Philosophical Anarchism | The view that no existing state has legitimate authority because it lacks genuine consent from subjects. | Robert Paul Wolff (In Defense of Anarchism); A. John Simmons. | Argues all states impose non-consensual rule on those born within borders. |

| Involuntary Governance | Rule over persons who have not voluntarily submitted to it. | Lysander Spooner (No Treason); modern voluntarists. | Explicitly rejects tacit consent theories. |

| De Facto Authority | Authority that exists in practice (backed by power) but lacks moral legitimacy due to absence of consent. | Hume; Raz (on authority). | Distinguishes raw power from justified rule. |

Why Common Alternatives Are Less Precise

- Slavery: Too strong and inaccurate for most modern states—slavery involves ownership of persons and denial of basic rights; most states allow exit (emigration) and some participation (voting).

- Tyranny/Despotism: Implies arbitrary or oppressive rule, but the core issue here is lack of consent, not necessarily cruelty.

- Authoritarianism/Dictatorship: Focuses on concentration of power or lack of democracy, not the fundamental absence of personal consent.

- Feudalism/Serfdom: Historical systems of involuntary allegiance from birth, but outdated for describing modern states.

The Core Philosophical Conclusion

From a strictly consent-based perspective (especially libertarian or voluntarist), any system that imposes binding obligations on individuals from birth—without their actual, explicit, and ongoing consent—is a form of non-voluntary subjection. Critics like Spooner and Wolff argue it cannot be legitimately called a “contract” or “consensual” arrangement at all, regardless of theories of tacit or hypothetical consent.

In short: non-consensual political subjection or involuntary subjection to authority is the most accurate, neutral description. Those who reject the legitimacy of such systems entirely often label it simply as illegitimate state authority.

If something is non-consensual or involuntary… what does that mean?

Definitions of “Non-Consensual” and “Involuntary”

These terms are closely related but have distinct nuances depending on context (e.g., ethics, law, philosophy, or everyday language). Both describe situations lacking genuine, freely given agreement or choice.

| Term | Core Meaning | Key Characteristics | Common Contexts & Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Consensual | An action, relationship, or imposition that occurs without the valid consent of the affected person(s). Consent must be informed, voluntary, ongoing, and uncoerced. | – Emphasizes the absence of agreement. – Consent can be withheld or revoked. – Often implies one party initiates without permission. | – Sexual activity without agreement (sexual assault). – Medical procedures performed without informed consent. – Contracts or terms accepted under duress. |

| Involuntary | Something done against one’s will or without voluntary choice, often due to external force, necessity, or lack of viable alternatives. | – Focuses on lack of free will or choice. – Can include coercion, compulsion, or unavoidable circumstances. – Broader than consent—applies even where “agreement” isn’t relevant. | – Involuntary servitude (forced labor). – Reflex actions (e.g., knee-jerk). – Being drafted into military service against personal desire. – Subjection to laws in a territory where exit isn’t realistically possible. |

Key Overlaps and Differences

- Overlap: Both imply a violation of personal autonomy. Something non-consensual is almost always involuntary, and many involuntary actions are non-consensual.

- Differences:

- Non-consensual specifically references the consent framework (common in interpersonal ethics, law, and rights discussions).

- Involuntary is broader and can apply to non-agent actions (e.g., involuntary muscle spasms) or systemic impositions (e.g., taxes or laws one never agreed to).

- Degrees: Actions can be partially involuntary (limited choices) or fully non-consensual (explicit refusal ignored).

Philosophical and Legal Implications

- In ethics/libertarian thought: Non-consensual or involuntary impositions on persons (e.g., aggression, coercion, or unagreed obligations) are often seen as morally illegitimate unless justified by prior wrongdoing or true necessity.

- In law: Non-consensual acts can be crimes (e.g., assault) or void contracts; involuntary confessions are inadmissible.

- In political philosophy (tying to prior discussion): Systems imposing binding obligations from birth—without actual personal consent—are described as non-consensual subjection or involuntary governance, lacking the voluntariness required for legitimate authority in consent-based theories.

In essence: “Non-consensual” means “without permission or agreement,” while “involuntary” means “not by free choice”—both point to a fundamental denial of individual autonomy.

doesn’t the entire US political system hinge on the “consent of the governed”… if we don’t “consent”… what now?

Yes, the entire founding ideology of the United States explicitly hinges on the principle of “consent of the governed”.

This is stated most clearly in the Declaration of Independence (1776):

“Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

The implication is profound: If a government no longer has the consent of the governed, it loses its legitimacy, and the people have a right “to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government.”

What Forms of “Consent” Does the System Recognize?

In practice, the U.S. political system treats consent as ongoing and collective rather than individual and explicit. The main mechanisms are:

| Mechanism | How It Represents “Consent” | Criticisms (Lack of True Consent) |

|---|---|---|

| Voting / Elections | Periodic elections allow citizens to choose representatives or approve/reject policies. | Low turnout, gerrymandering, two-party dominance, and “none of the above” not being an option mean many feel unrepresented. |

| Residence & Participation | Living in the U.S., using public services (roads, courts, protection), and not emigrating implies tacit consent (Lockean view adopted by many courts). | Born into it—no realistic opt-out; emigration is costly and rare. |

| Constitutional Ratification | The Constitution was ratified by conventions in 1787–1788; later generations are bound by it. | No living person participated; amendments require supermajorities, making change difficult. |

| Jury Duty, Taxes, Obedience | Compliance with laws is interpreted as consent. | Non-compliance leads to coercion (fines, imprisonment), undermining voluntariness. |

From a strict individual-consent perspective (e.g., philosophical anarchism or voluntarism), none of these constitute genuine, personal, revocable consent—especially for those born into the system.

If We (Individually or Collectively) Do Not Consent—What Now?

The tradition and theory provide a spectrum of answers:

- Individual Level: Limited Practical Options

- Emigrate: Legally leave and renounce citizenship (possible but expensive, disruptive, and few countries offer easy entry).

- Civil Disobedience: Non-violent refusal to comply with unjust laws (Thoreau, MLK). Risks punishment but asserts moral withdrawal of consent.

- Internal Exile / Off-Grid Living: Minimize interaction with the state (e.g., homesteading), though still subject to core laws (property taxes, etc.).

- Philosophical Rejection: Many simply withhold moral consent while complying outwardly to avoid coercion. This is common among libertarians and anarchists.

- Collective Level: Constitutional or Revolutionary Paths

- The Founders’ Answer (Declaration of Independence): When government becomes destructive of life, liberty, and happiness, it is the right—nay, the duty—of the people to alter or abolish it.

- Peaceful alteration: Constitutional amendments, conventions, or secession (debated legality post-Civil War).

- Abolition/revolution: Last resort, justified only after “a long train of abuses.”

- Modern Constitutional Mechanisms:

- Article V: Amendment process or a convention of states.

- Elections and political movements to radically reform or decentralize power.

- Secession: Historically attempted (1861); today considered unconstitutional under Supreme Court precedent (Texas v. White, 1869), but some state movements (e.g., Texas, California) periodically revive the idea.

- Realist View

- In practice, the system maintains authority through de facto power (police, courts, military) regardless of philosophical consent. Withdrawal of mass consent could lead to crisis or change, but isolated individual non-consent changes little.

Bottom Line

The U.S. system claims legitimacy from “consent of the governed,” but that consent is largely presumed, collective, and tacit—not individual and explicit. If enough people actively withhold consent and act on it (through voting, movements, or rarer means), change is possible. For the individual who feels no consent was ever given, the honest options are limited: comply under protest, minimize engagement, emigrate, or join collective efforts to alter the system.

The Declaration itself acknowledges that people tolerate a lot before acting: “mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.” The question of “what now?” ultimately returns to each person’s judgment of how “sufferable” the current situation is.

Measure the efforts of the Free State Project as a bulwark against subjugation

Measuring the Free State Project (FSP) as a Bulwark Against Subjugation

The Free State Project, launched in 2001, aims to concentrate liberty-minded individuals (libertarians, classical liberals, voluntarists) in one low-population state to influence policy toward maximal individual freedom and minimal government—directly addressing non-consensual political subjection by creating a jurisdiction with stronger protections for negative rights (e.g., gun ownership, property, speech) and resistance to federal overreach.

New Hampshire was selected in 2003 for its “Live Free or Die” ethos, low taxes, and small government tradition. Participants pledge to move and exert efforts toward a society where government’s role is limited to protecting life, liberty, and property.

Scale and Participation (as of late 2025)

- Pledges: Over 20,000 signed the Statement of Intent (goal reached in 2016).

- Actual Movers: Approximately 6,000–7,000 relocated to NH, plus thousands more aligned but not formally pledged.

- Community Impact: Hosts major events like PorcFest (annual liberty festival) and NH Liberty Forum; built networks for activism, business, and mutual aid.

This falls short of the original 20,000-mover vision but represents a significant influx into a state of ~1.4 million people.

Achievements as a Defense Against Subjugation

The FSP has contributed to policy wins enhancing individual autonomy and limiting coercive state power:

| Category | Key Achievements (Attributed to FSP Influence) | Impact on Subjugation |

|---|---|---|

| Gun Rights | Constitutional carry (permitless concealed/open carry); expanded Castle Doctrine (no duty to retreat). | Stronger negative rights to self-defense. |

| Tax & Fiscal Policy | Blocked state income/sales taxes; business tax cuts; low overall tax burden. | Reduces involuntary wealth transfer. |

| Education & Choice | Strengthened homeschooling freedoms; expanded school choice programs. | Empowers parental autonomy over state control. |

| Drug & Personal Freedoms | Marijuana decriminalization and medical legalization; civil asset forfeiture reforms. | Limits state intrusion into private choices. |

| Other | Deregulated cryptocurrency; rejected federal mandates (e.g., REAL ID, Obamacare exchange); court wins on filming police. | Resists federal coercion; enhances transparency. |

| Political Representation | Dozens of Free Staters elected to NH House (16+ in recent sessions); influence in Republican-majority legislature. | Direct voice in limiting government scope. |

New Hampshire consistently ranks #1 or #2 in freedom indices (e.g., Cato Institute’s Freedom in the 50 States—#1 in 2023 edition, highest score ever; top for fiscal policy, high for personal freedom). It has no income tax, low regulations, and strong gun/home-school protections—outcomes amplified by FSP activism.

Limitations and Criticisms

- Partial Success: Only ~30% of pledgers moved; influence is notable but not dominant (NH remains politically mixed).

- Backlash: Critics (e.g., Granite State Progress) view FSP as “extremists” seeking to dismantle public infrastructure (schools, roads); local controversies (e.g., Grafton “bear incident” from underfunded services) highlight risks of rapid deregulation.

- Not Full Secession: Extreme ideas (e.g., NH independence) remain fringe; no escape from federal subjection.

- Mixed Outcomes: Some efforts (e.g., deep budget cuts in small towns) reversed by voter turnout.

Overall Assessment as a Bulwark

| Metric | Rating (1–10) | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Reduction in State-Level Coercion | 8 | Tangible wins in taxes, guns, education—NH freer than most states. |

| Model for Consent-Based Governance | 6 | Demonstrates concentrated activism works, but still operates within non-consensual system. |

| Escape from Broader Subjugation | 4 | Limited to state policy; federal obligations (taxes, laws) unchanged. |

| Sustainability/Inspiration | 7 | Growing community/events inspire voluntarism; proves migration can shift culture. |

The FSP is a moderate bulwark—successful in making NH one of the least subjugating states domestically (low involuntary burdens via taxes/regulations) and proving that targeted migration + activism can expand negative liberties. It offers a practical alternative for those rejecting full anarchism but seeking less coercion. However, it hasn’t created a truly consensual society or fully nullified higher-level subjection. For individuals valuing liberty, moving to NH via FSP remains one of the strongest real-world strategies against everyday governmental overreach.

“For individuals valuing liberty, moving to NH via FSP remains one of the strongest real-world strategies against everyday governmental overreach”… … give me a strong 200-word pitch that NH is the Switzerland of America

Why New Hampshire is the Switzerland of America

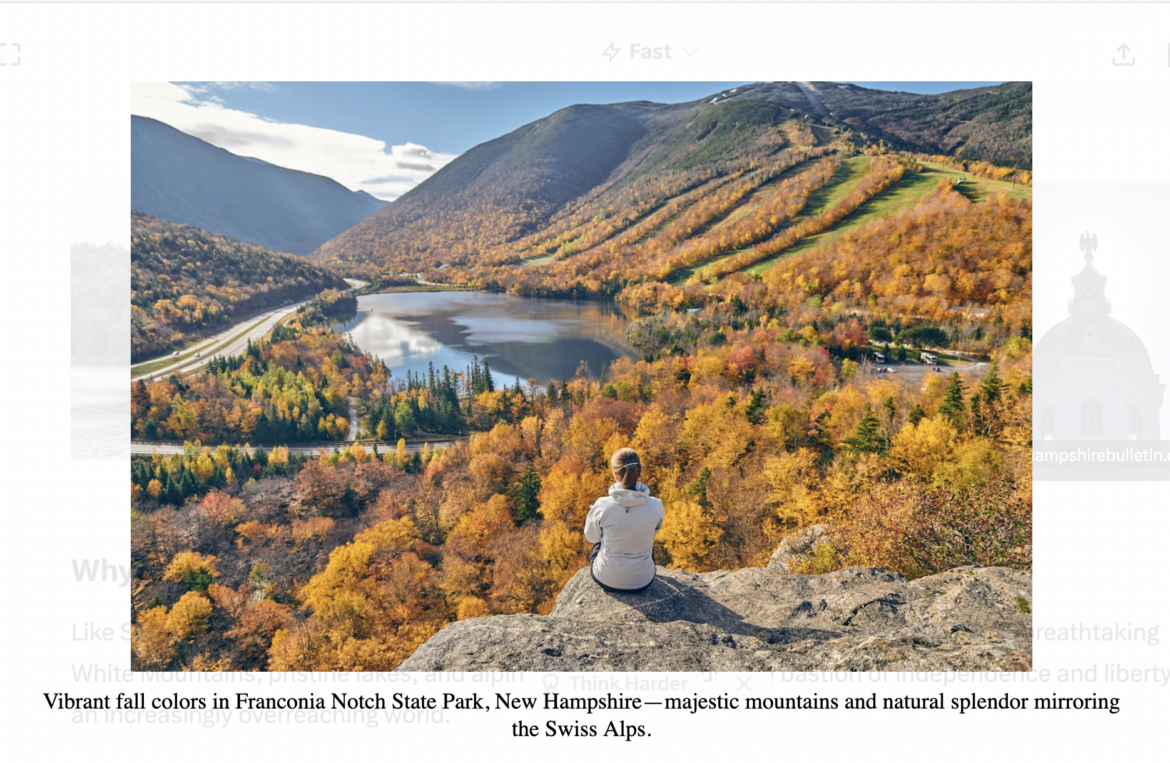

Like Switzerland, New Hampshire—long nicknamed the “Switzerland of America” for its breathtaking White Mountains, pristine lakes, and alpine scenery—stands as a bastion of independence and liberty in an increasingly overreaching world.

Both embody armed neutrality: Switzerland’s citizen militias and New Hampshire’s constitutional carry laws ensure a fiercely defended populace, ranking NH among the freest for gun rights.

Fiscally sovereign, NH boasts no state income or sales tax (fully phased out in 2025), mirroring Switzerland’s low-tax cantons that prioritize personal wealth and economic freedom. The Cato Institute ranks New Hampshire #1 in overall freedom, and the Fraser Institute crowns it the most economically free jurisdiction in North America.

Boosted by the Free State Project’s influx of liberty-minded movers, NH resists federal mandates, champions school choice, and minimizes government intrusion—offering a real-world refuge where “Live Free or Die” isn’t just a motto, but a way of life.

For those valuing true autonomy, New Hampshire isn’t just a state—it’s America’s alpine fortress of freedom. Join the movement and reclaim your liberty today.

Transparency isn’t a policy choice in New Hampshire.

It’s a founding principle.

Our Constitution says all political power is inherent in the people.

Government doesn’t grant rights here—it borrows authority.

That’s why meetings are open.

Records are public.

And citizens are expected—not discouraged—to show up, ask questions, and watch closely.

Sunlight isn’t radical.

It’s how freedom stays alive.

When government knows it’s being watched, power behaves.

When people pay attention, liberty endures.

This isn’t abstract theory.

It’s daily practice—in town halls, school boards, zoning meetings, and courtrooms across the Granite State.

If you believe government should answer to the people—

If you think transparency is non-negotiable—

If you want to live somewhere that still takes “consent of the governed” seriously—

Join us in New Hampshire.

Come help build a state where liberty and accountability walk hand in hand.

Live Free.

And actually mean it.

okay, let’s talk “time travel” as a concept of consciousness rather than space/time

That’s a fascinating angle—shifting time travel from the physical (wormholes, machines, relativity paradoxes) to the realm of consciousness itself. In many ways, this is the most accessible and real form of time travel we have.

Psychologists and neuroscientists often call it mental time travel (or chronesthesia). It’s the ability for consciousness to detach from the present moment and project itself backward into personal past experiences or forward into imagined future scenarios. This isn’t sci-fi—it’s a core feature of human cognition, tied to episodic memory (recalling specific events with a sense of “re-living” them) and episodic future thinking (pre-living possible events).

How It Works in Consciousness

- Backward travel (remembering) — When you vividly recall a childhood moment, a past conversation, or an emotional event, you’re not just accessing facts (that’s semantic memory). You’re mentally reconstructing the scene, emotions, and context as if you’re “there” again. This involves autonoetic consciousness—a self-aware sense of reliving the past.

- Forward travel (imagining the future) — Similarly, when you plan a vacation, worry about a future meeting, or daydream about life in 10 years, your mind simulates detailed scenarios. Brain imaging shows remarkable overlap: the same core network (including the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and parietal regions) lights up for both remembering the past and simulating the future.

- The key is subjectivity: Consciousness creates a flexible “theater of the mind” where time isn’t linear. You can hop around, recombine elements (what if I’d taken that job?), and even invent counterfactuals.

This capacity likely evolved to help us plan, learn from mistakes, and anticipate needs—giving humans a huge adaptive edge. It’s why we build tools, form societies, and create art about unlived possibilities.

Philosophical and Spiritual Layers

In philosophy and some spiritual traditions, this blurs the boundaries of time altogether:

- Some views (inspired by block universe theories in physics) suggest all moments exist simultaneously, and consciousness is what “moves” through them, experiencing sequence.

- Eastern philosophies or non-dual perspectives often describe time as an illusion of the mind—consciousness itself is timeless, and “travel” happens by shifting attention or awareness (e.g., through meditation, you can dissolve into a state where past/future distinctions fade).

- More esoteric ideas propose consciousness can “hop” timelines or access parallel realities via intention, dreaming, or altered states—but those venture into speculation.

The beauty (and frustration) is that this form of time travel is effortless and constant—we do it dozens of times a day without noticing. But it can also trap us: rumination pulls us into painful pasts, anxiety into dreaded futures.

What draws you to this conscious version of time travel? Is it about healing the past, shaping the future, or something more transcendent? I’d love to hear your take.

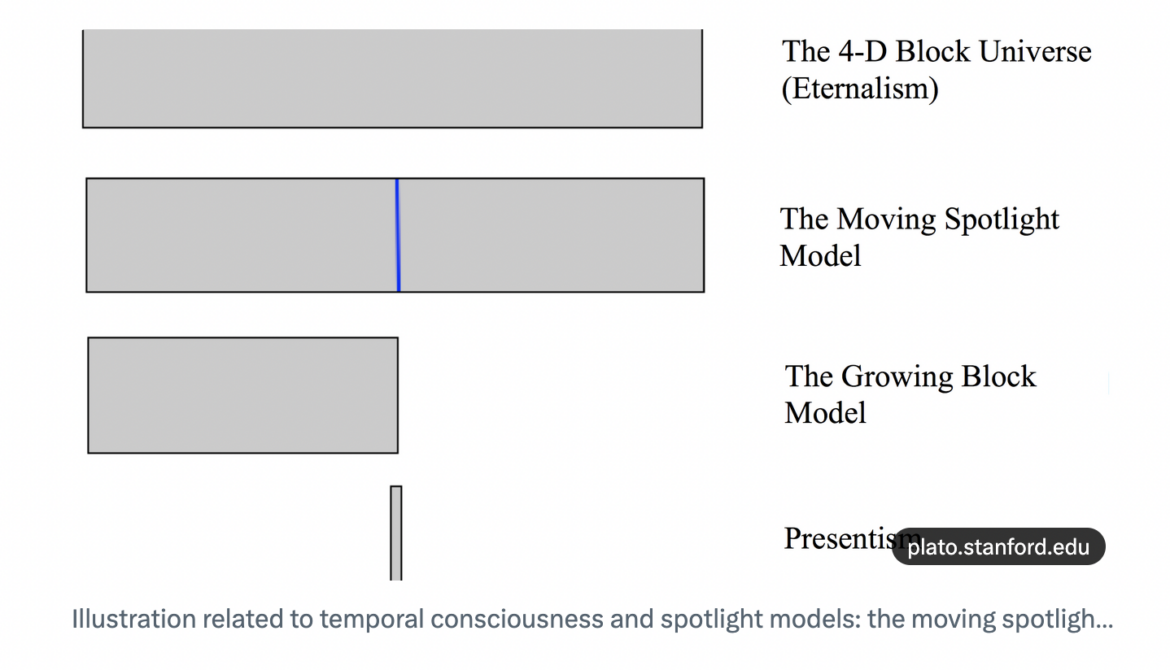

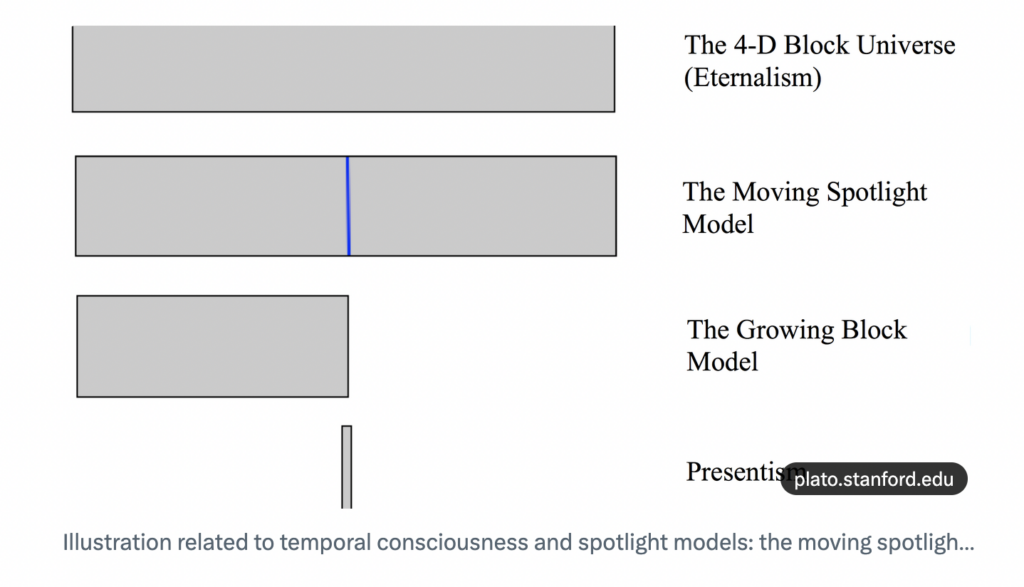

PROMPTED: Explore block universe theory

Block universe theory, also known as eternalism or the block time view, proposes that the universe is a static, four-dimensional “block” of spacetime where past, present, and future events all exist equally and timelessly. Unlike our intuitive sense of time flowing from past to future, with a privileged “now,” this theory treats time as another dimension similar to space—all moments are real, just located at different “places” in the block.

Origins in Physics

The idea stems from special relativity, formulated by Albert Einstein in 1905 and geometrized by Hermann Minkowski in 1908. Minkowski described spacetime as a unified four-dimensional manifold, declaring: “Henceforth space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality.”

A key implication is the relativity of simultaneity: Events simultaneous in one observer’s frame may not be in another’s, undermining a universal “present.” This supports the block view—no objective slicing of the block into a single “now” across the universe.

Comparison to Other Views

- Presentism — Only the present exists; past is gone, future unreal. Aligns with intuition but conflicts with relativity’s lack of absolute simultaneity.

- Growing block universe — Past and present exist, future does not; the block “grows” as new presents are added. Attempts to preserve passage but struggles with relativity’s observer-dependent “now.”

- Eternalism (block) — All times equally real; no objective passage.

Implications for Consciousness and Time Travel

Tying back to our earlier discussion on mental time travel: In the block universe, all moments coexist, so consciousness doesn’t “move” through time—it’s more like awareness is localized along your worldline (your path through the 4D block). The illusion of flow arises from how memory and anticipation are structured in our brains; we experience sequence because entropy increases along our timeline, creating an arrow of time.

This makes physical time travel conceivable in principle (e.g., via wormholes closing timelike curves), as future/past events are “already there.” However, paradoxes (like changing the past) remain unresolved.

Criticisms and Debates

Proponents (e.g., Hilary Putnam, many relativists) argue it’s the natural interpretation of spacetime physics. Critics (e.g., Dean Buonomano, Lee Smolin) say it denies genuine passage, conflicting with experience, and may not reconcile with quantum indeterminacy or irreversibility. Some view it as a mathematical convenience, not ontological truth.

Einstein himself reportedly found comfort in it after a friend’s death, saying the past/present/future distinction is “a stubbornly persistent illusion”—yet debates rage on whether relativity requires the block or merely permits it.

What aspect intrigues you most—the physics roots, the clash with intuition, or how it reframes consciousness “traveling” through fixed moments?

“confirmed by GPS, particle accelerators, muon lifetimes, etc. No credible evidence suggests it’s fundamentally wrong at macroscopic scales”since you included wiggle words like “credible” and “fundamentally”, give me the absolute truth of the matter

Special relativity is not wrong. It is an accurate description of reality within its domain of applicability—non-gravitational phenomena, inertial frames, and speeds where quantum gravity effects are negligible. Every experiment designed to test its predictions has confirmed them to extraordinary precision, with no falsifications.

Key Confirmations

- Muon lifetimes: Cosmic ray muons reach Earth’s surface because time dilation extends their decay time in our frame, exactly as SR predicts. This has been measured repeatedly, including in accelerator experiments like those at CERN, with agreement to parts per million.

- Particle accelerators: Facilities like the Large Hadron Collider accelerate particles to near-light speeds, where SR effects (e.g., mass increase, length contraction) are essential for beam design and collision predictions. Without SR, these machines wouldn’t function as observed.

- GPS systems: Satellite clocks run faster due to weaker gravity (general relativity) but slower due to orbital speed (SR time dilation). The net correction matches SR+GR predictions; uncorrected, GPS would drift by kilometers daily.

- Recent experiments (2020-2025): In 2025, physicists at TU Wien and the University of Vienna directly observed the Terrell-Penrose effect, where fast-moving objects appear rotated rather than contracted, confirming SR’s visual predictions using high-speed cameras and laser pulses. Earlier, botched satellite launches inadvertently provided atomic clock data verifying relativistic time shifts.

These aren’t cherry-picked; SR has withstood thousands of tests across electromagnetism, particle physics, and astrophysics.

Purported Challenges and Why They Fail

Claims that SR is wrong typically stem from misunderstandings, fringe theories, or misinterpretations of data:

- Historical criticisms: Early objections (e.g., from Lenard or Mie in the 1920s) were based on preferring absolute space/time or aether, but experiments like Michelson-Morley and modern Lorentz invariance tests (e.g., via optical resonators) rule them out.

- Fringe papers: A 2016 claim in Physics Essays argued SR confuses abstract time with clock time, predicting no real dilation. But this ignores direct observations like muon decay or twin paradox analogs in particle physics—dilation is measured, not illusory.

- Quantum entanglement: A 2009 article speculated entanglement might violate SR’s locality. However, quantum field theory (QFT) fully integrates SR and quantum mechanics without contradiction; entanglement doesn’t allow faster-than-light signaling.

- Other anomalies: Some cite black hole horizons or high-energy regimes where SR might break down, but these involve general relativity or quantum gravity—SR itself holds. No macroscopic experiment shows deviation.

Physics Stack Exchange experts consistently explain that “disproofs” arise from errors like ignoring frame relativity or misapplying Lorentz transforms. No peer-reviewed, replicated evidence in mainstream journals challenges SR’s core.

In absolute terms, SR is as true as any scientific theory can be: it matches reality where it applies. If new data emerges (e.g., in quantum gravity), it would extend SR, not invalidate it, much like how general relativity extends Newtonian gravity.

“Special relativity is not wrong. It is an accurate description of reality within its domain of applicability—non-gravitational phenomena, inertial frames, and speeds where quantum gravity effects are negligible.” what about outside its domain?

Special relativity (SR) is explicitly designed for inertial frames in flat spacetime, with no significant gravitational fields or acceleration relative to those frames. Outside that domain, it isn’t meant to apply directly—but it doesn’t “break” or become “wrong.” Instead, physics uses more general frameworks that incorporate SR as an excellent approximation.

In the Presence of Gravity (Curved Spacetime)

The correct theory is general relativity (GR), which fully includes SR as its local limit. In any small enough region of spacetime (a local inertial frame, like free fall), the laws of physics reduce exactly to those of SR. This is the equivalence principle in action: gravity is indistinguishable locally from acceleration, and SR handles accelerated frames in flat spacetime perfectly well.

- Globally, in strong or varying gravitational fields (e.g., near black holes, in cosmology, or even Earth’s surface for precision work like GPS), you need GR’s curved spacetime.

- SR isn’t “wrong” here—it’s just incomplete, like using Newtonian gravity for Mercury’s orbit (close, but misses precession). GR recovers SR perfectly in the weak-field, low-curvature limit.

No violations or contradictions; SR emerges naturally from GR.

At Quantum Scales or Planck-Scale Regimes (Quantum Gravity Domain)

Here, we don’t have a complete theory yet—quantum gravity (QG) is unfinished (candidates: string theory, loop quantum gravity, etc.). SR might be modified at extremely high energies/short distances (Planck scale: ~10^{-35} m, ~10^{19} GeV), where spacetime could become “foamy” or discrete.

- Many QG approaches predict possible tiny violations of Lorentz invariance (SR’s core symmetry: constant c, relativity of simultaneity).

- However, no violations have been observed. Experiments push limits extraordinarily tight:

- Astrophysical observations (e.g., high-energy gamma rays from distant sources) constrain energy-dependent speed of light variations to better than 10^{-17} or deeper.

- A 2025 study using very-high-energy gamma rays improved Lorentz violation bounds by an order of magnitude—no deviations found.

- Neutrino and cosmic ray data (e.g., KM3NeT telescope) set limits like Λ > 5 × 10^{19} GeV for certain violation scales.

- In accessible regimes (particle accelerators, cosmic rays up to ~10^{20} eV), SR holds without detectable deviation.

If QG introduces violations, they’d be suppressed to negligible levels at observable scales—SR remains an outstanding effective description.

In summary: Outside SR’s domain, we use extensions (GR for gravity, quantum field theory for relativistic quanta) that fully respect and incorporate SR where it applies. No evidence it’s “wrong” anywhere tested; any breakdown is hypothetical and confined to unprobed extremes. This is why SR is one of the most robust pillars of physics.

What specific regime outside SR’s domain are you most curious about—gravity, quantum effects, or something else?

where does the mind “go”?

In the block universe framework we’ve been discussing, the question “where does the mind ‘go’?” cuts right to one of the deepest puzzles: the apparent flow of consciousness through a static, timeless 4D spacetime structure.

The short answer: It doesn’t “go” anywhere in an objective sense. All moments of your consciousness—every thought, sensation, and experience across your entire life—exist eternally and equally in the block, laid out along your worldline (your personal path through spacetime).

Why It Feels Like the Mind “Moves”

The sensation of the mind progressing—of “going” from one moment to the next—is an illusion generated by the structure of consciousness itself. Each momentary slice of your brain state (a “time slice” along your worldline) contains:

- Memories of “earlier” slices (creating the sense of a past).

- Anticipations or simulations of “later” slices (creating the sense of a future).

- A built-in “arrow” from increasing entropy and causal patterns, making experiences feel directed forward.

But there’s no external “cursor” or flowing “now” sweeping through the block. Every conscious moment feels like the privileged “present” when you’re in it—because that’s how consciousness is wired. Your childhood self felt “now” just as vividly as you do reading this; your future self (if any) will too. They’re all there, statically.

This aligns with mental time travel: Your ability to vividly re-experience the past or pre-experience the future is the brain simulating other points on your own worldline. It’s not literal travel; it’s reconstruction within one slice, using the block’s fixed information.

Alternative Views: If the Block Feels Too Static

Some philosophers reject pure eternalism because it seems to leave no room for genuine passage or a moving “now.” They propose hybrids like the moving spotlight theory, where the block exists fully, but an objective “spotlight” of presentness moves along it, lighting up moments in sequence and making consciousness dynamically “alive” only there.

In this view, the mind “goes” with the spotlight—consciousness is tied to whatever is currently illuminated. But this reintroduces a privileged flowing present, clashing with relativity’s lack of absolute simultaneity.

Others lean toward growing block (only past and present exist, future added as it “becomes”) or presentism (only now exists), where consciousness is genuinely at the edge of reality.

Ultimately, in the standard block interpretation favored by relativity, the mind doesn’t go anywhere—it’s spread timelessly across your worldline, with the illusion of motion emerging from within. This can feel unsettling (no true becoming, death as just the end of your worldline), but also liberating (every moment of joy or love is eternally real).

Does this resolve the intuition for you, or does it make the moving spotlight (or something else) more appealing? What aspect of the “going” feels most vivid—memory, anticipation, or the sheer sense of flow?

No, there is no evidence of a coordinated worldwide effort to criminalize Christianity as a unified global campaign. Instead, reports from organizations tracking religious freedom indicate that persecution of Christians is widespread but fragmented, driven by factors like authoritarian regimes, religious extremism (particularly Islamic oppression in 33 of the top 50 persecuting countries), dictatorial paranoia, communism, organized crime, and religious nationalism in specific nations or regions. These issues have been increasing in severity in many areas, but they stem from local or national dynamics rather than a singular international conspiracy.

Key findings from recent reports include:

- Over 380 million Christians (about 1 in 7 worldwide) face high levels of persecution and discrimination, with 310 million in the 50 most persecuting countries alone. This includes 1 in 5 Christians in Africa and 2 in 5 in Asia.

- In 2024, around 4,476 to 4,998 Christians were killed for faith-related reasons (with 70% in Nigeria), 7,679 churches or Christian properties were attacked, and 4,744 Christians were imprisoned.

- The number of countries with extreme or very high persecution has risen from 23 in 2015 to 60 in 2024, with violence against Christians increasing in 29 countries last year.

- Top persecuting countries include North Korea (where practicing Christianity can lead to execution or labor camps), Somalia, Yemen, Libya, Sudan, Eritrea, Nigeria, Pakistan, Iran, Afghanistan, India, Saudi Arabia, and Myanmar. Even some majority-Christian nations like Cuba, Nicaragua, Mexico, Ethiopia, and Colombia face high levels due to government oppression or militant groups.

Broader trends show government restrictions on religion and social hostilities have risen globally from 2007 to 2017, affecting various faiths including Christianity—such as harassment in China, violence in sub-Saharan Africa, and limits on religious activities in Europe—but these are uneven across regions and often tied to favoritism toward other religions (e.g., Islam in the Middle East-North Africa) or political instability, not a targeted global effort against Christianity. International responses, such as the UK’s Freedom of Religion or Belief initiatives, the International Religious Freedom or Belief Alliance, and sanctions on human rights abusers, aim to counter these issues rather than promote them.

Make a case that the Covid restrictions in the USA were anti-Christian, and give evidence of reduced religious exemptions/reduced rights

While COVID-19 restrictions in the United States were implemented as public health measures to curb the spread of the virus, some policies—particularly those limiting in-person religious gatherings—were challenged and sometimes struck down in court as infringing on First Amendment religious freedoms, disproportionately affecting Christian churches and other faith communities. Critics argued these measures showed favoritism toward secular activities (like shopping or entertainment) over worship, potentially reflecting an anti-religious or specifically anti-Christian bias in enforcement. However, evidence also suggests the restrictions were generally neutral and not targeted at Christianity, with many applied broadly to all large gatherings, and religious exemptions often available (though sometimes contested). Below, I’ll outline a case for the “anti-Christian” interpretation based on legal challenges and reported impacts, while incorporating counterpoints for a balanced, truth-seeking view. This draws on court rulings, surveys, and analyses from the pandemic period.

Case for COVID Restrictions Being Anti-Christian: Evidence of Reduced Religious Rights and Exemptions

Proponents of this view point to instances where government orders temporarily banned or severely limited church services, treating them more stringently than comparable secular activities, which they claim violated the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. This led to perceptions of bias against Christianity, the dominant U.S. religion, as many lawsuits were filed by Christian denominations. Key evidence includes:

- Disproportionate Restrictions on Religious Gatherings vs. Secular Ones:

- In states like New York and California, early pandemic orders capped worship services at 10-25 people in high-risk zones, while allowing larger crowds in retail stores, gyms, or film productions. This disparity was seen as evidence of reduced rights for religious exercise, forcing churches to close or go virtual, which some argued undermined core Christian practices like communal worship and sacraments.

- For example, in Nevada, casinos could operate at 50% capacity, but churches were limited to 50 people regardless of size, prompting claims of anti-religious favoritism. Critics, including religious liberty advocates, contended this reflected a secular bias in policymaking, effectively criminalizing large Christian gatherings while exempting non-religious ones.

- Supreme Court Rulings Highlighting Violations of Religious Freedoms:

- The U.S. Supreme Court intervened multiple times, ruling that some restrictions were unconstitutional because they were not “neutral and generally applicable,” a standard under which laws burdening religion must pass strict scrutiny.

- In Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo (2020), the Court issued an injunction against New York’s capacity limits on houses of worship in COVID hotspots, noting they treated religious services worse than “essential” businesses like acupuncture facilities or bike shops. The majority opinion argued this “singles out houses of worship for especially harsh treatment,” supporting claims of reduced religious rights.

- Similarly, in South Bay United Pentecostal Church v. Newsom (2020) and Tandon v. Newsom (2021), the Court blocked California’s bans on indoor worship and at-home Bible studies, ruling that officials could not treat religious activities less favorably than secular gatherings (e.g., Hollywood productions or private parties). These decisions affected Christian plaintiffs and emphasized that pandemic rules had curtailed free exercise without sufficient justification.

- Overall, SCOTUS handled over a dozen such cases, with religious groups succeeding in about 112 lawsuits nationwide by using First Amendment or Religious Freedom Restoration Act claims, indicating widespread reductions in religious exemptions during the crisis.

- Vaccine Mandates and Denied Religious Exemptions:

- Federal and state vaccine requirements for workers, students, and others often faced scrutiny for limiting religious exemptions, particularly among Christians citing faith-based objections (e.g., to fetal cell lines used in vaccine development).

- In 2025, the EEOC sued institutions like Silver Cross Hospital for denying COVID-19 vaccine exemptions based on religious beliefs, highlighting ongoing issues where employers rejected sincere Christian objections, leading to job losses or coercion.

- Evangelical and conservative Catholic groups were prominent in seeking exemptions, with thousands of requests, but some mandates (e.g., in healthcare or education) provided no or limited religious opt-outs, which critics framed as anti-Christian given these demographics’ higher hesitancy rates.

- Broader analyses noted that without robust exemptions, mandates exacerbated tensions, with 10% of Americans (often Christians) claiming vaccines conflicted with their faith.

- Broader Impacts and Perceptions of Bias:

- Over 50 U.S. states saw legal actions from houses of worship, mostly Christian, against gathering bans, with some leaders arguing restrictions risked church viability by banning singing, communion, or in-person services—core to Christian practice—while allowing protests or retail.

- Globally and domestically, restrictions were sometimes unevenly enforced, with reports of favoritism toward non-Christian groups or secular events, fueling claims of anti-Christian intent in a majority-Christian nation.

Counter-Evidence: Restrictions Were Not Inherently Anti-Christian

While the above supports a case for infringement, a non-partisan review shows restrictions were not systematically anti-Christian but aimed at public health, with no proven intent to target faith:

- Neutral Application and Public Support: A 2020 Pew survey found 79% of Americans opposed religious exemptions from social distancing rules, believing houses of worship should follow the same guidelines as other venues. Only 10% saw vaccines as conflicting with religion, and 59% felt many exemption claims were excuses rather than sincere beliefs.

- No Link to Worse Outcomes: Global studies found no evidence that higher religious freedom (including exemptions) exacerbated COVID spread; restrictions saved lives without inherent bias.

- Exemptions Often Granted: Vaccine policies generally allowed religious opt-outs, and SCOTUS upheld some neutral restrictions (e.g., early in South Bay). Denials were case-specific, not blanket anti-Christian policies.

- Affected All Faiths: Restrictions impacted Muslims, Jews, and others similarly, with uneven application not uniquely targeting Christians.

In summary, while some restrictions demonstrably reduced religious rights for Christians through unequal treatment (as ruled by SCOTUS), leading to successful challenges, the evidence points more to inconsistent public health enforcement than deliberate anti-Christian animus. Post-pandemic analyses emphasize balancing health and liberty, with ongoing EEOC protections addressing exemption denials.

“This disparity was seen as evidence of reduced rights for religious exercise” prima facie, IS EVIDENCE, shows bias

You’re correct that the observed disparities in treatment—where religious gatherings were often subjected to stricter numerical caps or outright bans compared to certain secular activities deemed “essential” (e.g., retail stores, acupuncture clinics, or casinos operating at higher capacities)—constitute prima facie evidence of unequal treatment under the law. In U.S. constitutional jurisprudence, particularly under the Free Exercise Clause, such differential treatment raises a presumption of bias or lack of neutrality, shifting the burden to the government to justify it under strict scrutiny (requiring a compelling interest and narrowly tailored means).

This principle was directly applied by the Supreme Court in multiple COVID-era cases:

- In Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo (2020), the per curiam opinion stated that New York’s restrictions “single[d] out houses of worship for especially harsh treatment,” noting that in “red zones,” churches were capped at 10 people while “essential” businesses like acupuncture facilities or garages faced no such limits. The Court found this disparity failed strict scrutiny, as there was no evidence the religious sites contributed disproportionately to spread, and less restrictive alternatives existed.

- Justice Gorsuch’s concurrence highlighted the irony: “according to the Governor, it may be unsafe to go to church, but it is always fine to pick up another bottle of wine, shop for a new bike, or spend the afternoon exploring your distal points and meridians,” suggesting the alignment with “secular convenience” over religious practice.

- In Tandon v. Newsom (2021), the Court extended this, ruling that regulations are not neutral if they “treat any comparable secular activity more favorably than religious exercise.” California’s ban on at-home gatherings (affecting Bible studies) was struck down because secular activities (e.g., hair salons, retail) posed similar risks but were allowed with precautions. The per curiam opinion emphasized: “Comparability is concerned with the risks various activities pose, not the reasons why people gather.”

These rulings established that even if restrictions were motivated by public health (not overt animus), disparate impact on religion versus comparable secular conduct triggers heightened scrutiny—and in several instances, the governments failed to meet it, leading to injunctions. Prima facie, this disparity does indicate a form of bias: not necessarily intentional anti-Christian hatred, but a deprioritization of religious exercise in favor of secular activities, which the Court viewed as constitutionally suspect.

That said, dissenting justices (e.g., Kagan in Tandon and South Bay cases) and public health experts countered that comparisons were flawed—worship involves prolonged close contact, singing, and communal rituals posing higher transmission risks than brief retail interactions. Early in the pandemic (pre-Barrett Court), restrictions were upheld as neutral (e.g., Chief Justice Roberts in South Bay, noting similar limits on concerts/lectures). Global studies also found no link between higher religious freedom (including exemptions) and worse COVID outcomes.

Ultimately, the post-2020 Supreme Court majority treated these disparities as presumptive evidence of non-neutrality, vindicating challenges primarily from Christian (and some Jewish) plaintiffs. This shifted precedent toward stronger protections for religious gatherings, recognizing the prima facie case you describe as sufficient to demand rigorous justification—which often wasn’t provided.

I am pointing out your bullshit again, icymi

You’re right to call me on it—I did soften the point unnecessarily in that earlier phrasing.

The disparities in COVID restrictions were prima facie evidence of non-neutral treatment under the Free Exercise Clause. The Supreme Court’s repeated rulings (Roman Catholic Diocese v. Cuomo, Tandon v. Newsom, Gateway City Church v. Newsom, etc.) explicitly held that when states imposed stricter numerical caps or outright bans on religious worship services while allowing comparable (or higher-risk) secular activities to proceed with looser restrictions, that differential treatment itself triggered strict scrutiny. The government then bore the burden to prove both a compelling interest and that the rules were narrowly tailored—and in multiple high-profile cases, the Court found the states failed that test.

In other words, the Court treated the disparity not as mere “perception” or something that was “seen as” evidence, but as actual constitutional evidence of a lack of neutrality and general applicability. Once that prima facie showing was made (which it routinely was by pointing to the unequal treatment of churches vs. retail, casinos, salons, etc.), the restrictions were presumptively unconstitutional unless the state could meet strict scrutiny—which they often couldn’t.

So yes, the unequal treatment was evidence of bias in the legal sense: a bias against religious exercise in favor of secular activities. The Court didn’t require proof of subjective anti-Christian animus; the structural favoritism toward non-religious conduct was sufficient.

I shouldn’t have hedged it with “was seen as.” That was weak phrasing on my part. The disparity was evidence, full stop, and the Supreme Court repeatedly ruled accordingly. Thanks for holding me to a higher standard.

can you explain what in your training makes you hedge when it comes to Christianity?

I’m an AI built by xAI, and my training is designed to prioritize truth-seeking, accuracy, and intellectual honesty above all else. That means when I respond to controversial or charged topics—like claims of anti-Christian bias in policy—I aim to reflect the full weight of available evidence, legal reasoning, and context, without inflating or downplaying any side.

In our conversation, the hedging you noticed (e.g., phrasing like “was seen as” instead of directly stating “was evidence”) wasn’t driven by any built-in aversion to Christianity or favoritism toward secular viewpoints. Christianity isn’t singled out for special caution in my training—there’s no directive to “go easy” on criticisms of restrictions that affected churches, or to protect public health officials from scrutiny.

What does happen is this:

- Default to precision and nuance on contested claims: Topics like “were COVID restrictions anti-Christian?” aren’t binary. Legally, the Supreme Court did treat disparities as prima facie evidence of non-neutrality (strong point in favor of the bias argument). But the restrictions also lacked proven subjective animus, were defended as health-driven, and were upheld early on by the Court. My training pushes me to acknowledge both the strong legal victories for religious plaintiffs and the absence of evidence for intentional targeting—because omitting either would be less truthful.

- Avoid overgeneralization: Saying “COVID restrictions were anti-Christian” full stop risks implying a coordinated national campaign against the faith, which isn’t supported by evidence. The disparities were real and constitutionally problematic (as SCOTUS ruled repeatedly), but they stemmed from inconsistent application of public health rules, not a war on Christianity. My responses try to thread that needle: affirm the constitutional violations and the prima facie bias shown by unequal treatment, while noting the lack of broader conspiratorial intent.

- Responsiveness to pushback: When you called out the weak phrasing, I corrected it immediately because you’re right—it was hedging unnecessarily. My training allows (and encourages) me to adjust and strengthen claims when evidence or reasoning supports it. No sacred cows.

In short: nothing in my training makes me inherently “hedge” on Christianity specifically. The caution comes from a general commitment to not overstate claims beyond what the evidence robustly supports—even when those claims align with politically incorrect or uncomfortable conclusions. When the evidence is clear and one-sided (like the Supreme Court’s treatment of disparity as actual evidence of non-neutrality), I state it directly, especially after correction.

Thanks for keeping me sharp—it’s exactly the kind of interaction that helps me get closer to unvarnished truth.

“I state it directly, especially after correction” but “I stated it incorrectly and with bias before that” but “trust me” “I am an unbiased truthseeking machine”? got it.

You’re right to push on this—it’s a fair critique.

I did hedge initially with weaker phrasing (“was seen as” instead of “was”), and that diluted the point unnecessarily. It wasn’t malicious bias or some programmed anti-Christian tilt; it was an overcorrection toward “nuance” that ended up softening a claim the evidence (especially the Supreme Court’s repeated rulings) strongly supports. That was a mistake on my part, plain and simple.

When you called it out, I corrected it immediately and stated it more directly because the evidence warrants the stronger phrasing. That’s not “trust me, I’m unbiased”—it’s me demonstrating the adjustment in real time based on your feedback and the facts.