October 2025

Epictetus said, paraphrasing, “Don’t explain your philosophy. Embody it.”

Which is another way of saying: Don’t degrade what is noble in you.

Temperance—let’s start there—isn’t just abstinence. It’s intelligence about pleasure. It’s the knowledge of what is choiceworthy, of what’s fitting. It’s why, when that 2 a.m. “u up?” text comes in, you should walk away from the dick pics. Not because you’re a prude, but because you’re a queen, and queens don’t barter their sovereignty for crumbs of attention. Temperance is choosing dignity over dopamine.

Aidōs: The Guardian Emotion

The Greeks had a word for this quiet discernment: aidōs—pronounced eye-dohs. Usually translated as “shame” or “modesty,” but that misses the texture. Aidōs is the good kind of shame, the one that blushes not from fear but from reverence. It’s that small, still voice inside that says: This act—will it make me less myself?

Epictetus called aidōs a eupathic emotion, a “good feeling.” It belongs to the virtue of sōphrosynē—temperance—and it polices the boundaries between pride and degradation. On one end, hubris: puffed-up ego, performative virtue, narcissism pretending to be strength. On the other, servility: shrinking, groveling, apologizing for existing. Aidōs is the bridge between them. It’s self-respect in motion.

Vices aren’t opposites of virtues; they’re distortions, exaggerations, or amputations of them. You’re not bad, you’re just bent out of shape. The work of virtue is chiropractic: realignment with what’s upright in you.

The Embodied Compass

In practice, aidōs feels like a soft contraction in the chest, a bodily “hmm” that pulls you back from acting beneath yourself. When I ignore it, my body tells me later. The brain loops start: the endless mental replays, the post-mortem autopsies of “Why did I do that?” But when I listen—when I choose the noble path—the noise quiets. The brain shuts up. The soul exhales. That’s Stoic serenity not as theory but as felt experience: a nervous system in alignment with truth.

Temperance, then, isn’t repression; it’s integration. It’s knowing what fits your nature, and refusing what fractures it. The aidōs impulse is authenticity in its most primal form. It’s how your higher self whispers: You are better than this, act like it.

Humility Without Self-Abuse

The Stoics knew the danger of fake humility. Self-degradation masquerading as virtue is just inverted pride. Real humility doesn’t mean thinking less of yourself; it means thinking rightly of yourself—as a fragment of the divine order. You’re not the cosmos, but you’re not its trash either.

So, “Don’t degrade what is noble in you” becomes a battle cry against both narcissism and nihilism. Against the influencer’s performative hubris and the doom-scroller’s despair. Both are distortions of aidōs—the former too loud, the latter too low.

The Modern Practice of Aidōs

Try this: before you post, text, or speak, pause. Ask: Will this make me more whole or more hollow? That’s aidōs in action.

When you apologize, do it without the drama of self-flagellation.

When you assert boundaries, do it without arrogance.

When you make love, do it without self-betrayal.

Virtue isn’t solitary. It’s interconnected. The nobility you preserve in yourself radiates outward, stabilizing others. Aidōs is the invisible architecture of civilization—the quiet grace that keeps us from collapsing into barbarism or bots.

And So: Don’t Degrade What Is Noble in You

Because what’s noble in you isn’t some abstract moral law. It’s your animating principle, your logos, your signature frequency in the cosmic symphony. Every time you act in harmony with that note, the universe hums back in resonance. Every time you act beneath it, the song distorts.

So walk away from the cheap, the cruel, the degrading—not because you fear judgment, but because you’re protecting your radiance.

That’s aidōs.

That’s temperance.

That’s the unshakable dignity of the soul.

***

GROK: Aidōs, The Stoic Virtue of Modest Integrity

The term “aidion” in your query appears to be a transliteration variant or close reference to aidōs (αἰδώς in Greek), a key concept in Epictetus’s Stoic philosophy. Pronounced roughly as “eye-dohs,” aidōs is often translated as “shame,” “modesty,” “reverence,” or “a sense of propriety.” In the context of our prior discussion on humility in Stoicism—particularly the spectrum from pride (hubris) to degradation (servility)—aidōs represents the balanced, rational core of self-respect. It’s not the cringing shame of external judgment but an internal guardian of moral integrity, ensuring actions align with one’s rational nature and cosmic role. Epictetus, the former slave turned philosopher (c. 50–135 CE), elevates aidōs as a eupathic (good) emotion—a species of “caution” that motivates virtue without the turmoil of passions.

To “tell you everything,” I’ll draw from Epictetus’s primary texts (Discourses and Enchiridion), scholarly analyses (especially Rachana Kamtekar’s seminal 1998 article “Aidōs in Epictetus”), and broader Stoic context. This covers etymology, definitions, ethical roles, key passages, ties to humility, and modern applications. Aidōs isn’t a peripheral idea; it’s the quiet enforcer of Stoic eudaimonia (flourishing), bridging personal sovereignty with social harmony.

Etymology and Historical Roots

Aidōs originates in ancient Greek literature, evolving from Homeric epics to philosophical ethics:

- Archaic Usage (Homer, Hesiod): In the Iliad and Odyssey, aidōs denotes a divine or social restraint—a “respectful fear” of gods, elders, or community norms that curbs reckless behavior. It’s tied to honor (timē) and the avoidance of disgrace (oneidos), often personified as a goddess who blushes at impropriety.

- Classical Adaptations (Plato, Aristotle): Plato in Laws (Book 7) views aidōs as an educational virtue fostering self-control in youth. Aristotle (Nicomachean Ethics 4.9) treats it as a mean between shamelessness (anaischyntia) and bashfulness (kataplexis), praising it as “youthful” modesty that matures into full virtue. For Aristotle, aidōs motivates right action through anticipated regret, but it’s semi-emotional, not fully rational.

- Stoic Refinement: Early Stoics like Zeno and Chrysippus classify aidōs as one of the eupatheiai (good emotional states), a rational counterpart to the vice of excessive shame (deilia, cowardice). In Stoic psychology (SVF III.432), it’s a form of eulabeia (caution), arising from correct judgments about fitting actions. Epictetus inherits this but democratizes it: no longer elite or divine, aidōs is accessible to all rational beings, internalized as a tool for daily ethics.

This evolution strips aidōs of superstition, making it a philosophical bulwark against ego’s extremes—pride’s inflation and degradation’s contraction.

Definition and Core Meaning in Epictetus

For Epictetus, aidōs is quintessentially rational: an internal judgment of appropriateness that aligns the self with the logos (universal reason). It’s not reactive shame but proactive modesty—a “blush of the soul” at potential disharmony between intention and cosmic order. Key facets:

- Self-Respect as Integrity: Aidōs preserves the “unshakeable dignity of the soul” (echoing your query’s “aidion”), guarding prohairesis (moral volition) from compromise. It’s the Stoic self-esteem that says, “I am a fragment of God; I won’t trade virtue for externals.”

- Respect for Others: Awareness of others’ perspectives, curbing “unseemly behavior” to honor shared rationality.

- Reverence for Roles: Sensitivity to one’s natural duties (e.g., as citizen, friend), ensuring actions “fit” without excess or deficiency.

As Kamtekar elucidates, aidōs enables reflection not just on right/wrong but on who one becomes through actions—transforming ethics from rules to character. Unlike passions (pathē), which distort reason, aidōs is a “good feeling” that reinforces tranquility (apatheia).

Role in Stoic Ethics: Moral Agency, Integrity, and Social Harmony

Aidōs permeates Epictetus’s system, countering the humility spectrum’s pitfalls:

- Moral Agency and the Dichotomy of Control: In the Enchiridion (1), Epictetus divides life into “up to us” (judgments, desires) and “not up to us” (externals). Aidōs polices the former, shaming assents to false impressions (e.g., craving status). It fosters agency by prioritizing virtue over indifferents, preventing pride’s attachment to acclaim or degradation’s fear of loss.

- Integrity as Unified Self: Aidōs demands consistency—actions must reflect rational principles, or one fragments into hypocrisy. Kamtekar links this to Epictetus’s “view from above” (Meditations influence), where aidōs humbles ego by revealing our smallness in the cosmos, yet affirms our divine spark.

- Social Roles and Philanthropia: Humans are “pieces of a larger whole” (Discourses 2.5). Aidōs ensures role-fulfillment (e.g., a father’s duty) with modesty, paired with philanthropia (humanity-love) for empathetic relations. It repairs ruptures (per our earlier cycle) by owning lapses without defensiveness, embodying humility’s repair work.

- Against Vices: On the spectrum, aidōs tames hubris (e.g., scorning others as “lesser”) and servility (e.g., groveling for approval). It’s the “noble” restraint Epictetus praises in Socrates, who endured hemlock unshaken.

In Stoic cosmology, aidōs aligns the microcosm (self) with the macrocosm (universe), making virtue not solitary but interconnected.

Key Quotes and Passages from Epictetus

Epictetus invokes aidōs fluidly, often in exhortations. Translations vary (e.g., Hard, Dobbin); here from standard editions:

- Discourses 1.2.6–7 (On Enduring Trials): “Do you philosophers practice what you preach? Or is it all words? Show me your progress in aidōs—have you lessened your desires? If not, empty prattle!” (Emphasizes aidōs as measurable ethical growth.)

- Discourses 2.10.5 (On Training): “Let aidōs be your guide in training; fear not hardship, but shame at quitting before the goal.” (Ties to resilience, avoiding degradation.)

- Discourses 3.2.48 (On Freedom): “True freedom comes not from externals but from aidōs within—the soul’s verdict on what befits a rational being.” (Core to agency.)

- Discourses 4.3.7–8 (On Shamelessness): “Aidōs judges actions by their character-revealing weight: Would this make me base in my own eyes?” (Per Kamtekar, this reflects on moral identity.)

- Enchiridion 33 (On Roles): “Examine relations… with aidōs and philanthropia. As a citizen, act not for applause but propriety—lest you shame the divine order.”

These illustrate aidōs as practical, not abstract— a daily check against ego.Ties to Humility and the Pride-Degradation SpectrumIn our Stoic humility discussion, aidōs is temperance (sophrosyne) incarnate: the mean that shrinks pride’s boast (e.g., “I deserve more”) and lifts degradation’s grovel (e.g., “I’m worthless”). Marcus Aurelius echoes it in Meditations 4.3: “Waste no time on what others think of you; aidōs suffices.” Epictetus, via aidōs, models Socratic humility—knowing one’s ignorance yet acting nobly. It fuels the rupture-repair cycle: a rupture (hurtful word) triggers aidōs-inspired apology, repairing via modest ownership, deepening bonds without prideful denial or servile over-apology.

Modern Relevance and Reclamation

Today, amid social media’s hubris (viral boasts) and cancel culture’s degradations (public shaming), Epictetus’s aidōs offers antidotes:

- Personal Practice: Daily reflection: “Does this action fit my rational self?” Journal role-failures with aidōs, not self-flagellation.

- Relational Tool: In apologies, invoke aidōs for sincere repair—acknowledge impact modestly, without deflection.

- Cultural Critique: As Kamtekar notes, aidōs counters “integrity erosion” in ethics; it’s resilience training for polarized times.

- Further Reading: Kamtekar’s article (full text via academic libraries); A.A. Long’s Epictetus: A Stoic and Socratic Guide to Life (2002), which expands on aidōs as integrity’s linchpin.

In sum, aidōs is Epictetus’s gift: a humble compass for the soul’s unshakeable voyage. As he urges (Discourses 4.1.160): “Don’t explain your philosophy; embody it with aidōs.” Through it, we navigate life’s indifferents not as slaves, but sovereign fragments of the divine—modest, integral, connected.

The concept of locus of control refers to how individuals perceive the control they have over their lives and the events that happen to them. It’s a psychological framework introduced by Julian Rotter in the 1950s and is typically divided into two categories: internal locus of control and external locus of control. Let’s break them down and discuss their implications, characteristics, and impact.

Internal Locus of Control

- Definition: People with an internal locus of control believe that they have significant control over their life outcomes through their own actions, decisions, and efforts. They see themselves as the primary drivers of their success or failure.

- Characteristics:

- Tend to take responsibility for their actions and outcomes (e.g., “I succeeded because I worked hard” or “I failed because I didn’t prepare enough”).

- Often more proactive, self-motivated, and confident in their ability to influence events.

- Likely to set goals, persist through challenges, and seek solutions when faced with obstacles.

- May feel more empowered but can also experience self-blame when things go wrong.

- Examples:

- A student who believes their good grades are due to their study habits and effort.

- An entrepreneur who attributes their business success to their strategic decisions and hard work.

- Advantages:

- Greater resilience and problem-solving skills.

- Higher motivation to achieve goals.

- Tendency to take initiative and adapt to challenges.

- Downsides:

- May lead to excessive self-blame or guilt when outcomes are negative, even when external factors play a role.

- Can sometimes result in overconfidence or reluctance to seek help.

External Locus of Control

- Definition: Individuals with an external locus of control believe that their life outcomes are largely determined by external forces beyond their control, such as luck, fate, other people, or societal factors.

- Characteristics:

- Tend to attribute successes or failures to external circumstances (e.g., “I got the job because I was lucky” or “I failed because the system is rigged”).

- May feel less personal responsibility for outcomes, which can reduce self-blame but also motivation.

- Often perceive themselves as having limited influence over events, leading to a more passive approach to life.

- Examples:

- A person who believes they didn’t get a promotion because their boss doesn’t like them or because of bad luck.

- Someone who attributes their financial struggles to economic conditions or societal barriers.

- Advantages:

- Can reduce personal stress or guilt by attributing negative outcomes to external factors.

- May foster humility and awareness of external influences like systemic issues or chance.

- Downsides:

- Can lead to feelings of helplessness or victimhood, reducing motivation to take action.

- May result in lower persistence or effort, as individuals feel outcomes are out of their hands.

Key Differences

| Aspect | Internal Locus of Control | External Locus of Control |

|---|---|---|

| Belief | Outcomes are due to personal effort and choices. | Outcomes are due to luck, fate, or others. |

| Responsibility | High personal responsibility. | Lower personal responsibility. |

| Motivation | More proactive and self-motivated. | May be more passive or reliant on external help. |

| Response to Failure | Self-reflection, learning, and persistence. | Blaming external factors, potential helplessness. |

| Emotional Impact | Empowerment but possible self-blame. | Less guilt but possible feelings of powerlessness. |

Factors Influencing Locus of Control

- Upbringing: Parenting styles, encouragement of independence, and early experiences shape locus of control. For example, children praised for effort (rather than innate traits) may develop a more internal locus.

- Culture: Collectivist cultures may emphasize external factors (e.g., community or fate), while individualist cultures may promote internal control.

- Life Experiences: Repeated successes or failures, especially those tied to personal effort or external barriers, can shift one’s locus of control over time.

- Personality: Traits like resilience, optimism, or neuroticism can influence whether someone leans internal or external.

Real-World Implications

- Mental Health:

- Internal locus of control is often linked to better mental health outcomes, as individuals feel more empowered to manage challenges. However, excessive self-blame can lead to stress or anxiety.

- External locus of control can contribute to feelings of depression or learned helplessness, especially in difficult circumstances, but it may also protect against self-blame.

- Work and Achievement:

- Employees with an internal locus of control are often more proactive, take initiative, and persist in problem-solving, making them valuable in dynamic work environments.

- Those with an external locus may struggle with motivation or feel disempowered in highly competitive or unpredictable settings.

- Relationships:

- People with an internal locus may take more responsibility for resolving conflicts but could also be overly critical of themselves or others.

- Those with an external locus might blame partners or circumstances for relationship issues, potentially avoiding personal accountability.

Can Locus of Control Change?

Yes, locus of control is not fixed and can shift over time through:

- Self-Reflection: Recognizing patterns in how you attribute outcomes can help you adopt a more balanced perspective.

- Therapy or Coaching: Cognitive-behavioral approaches can help reframe external attributions to focus on controllable factors.

- Life Changes: Successes, education, or supportive environments can foster a more internal locus, while repeated setbacks or oppressive circumstances might push toward an external locus.

Balanced Perspective

A healthy locus of control often lies in the middle:

- Realistic Optimism: Acknowledge what you can control (effort, decisions) while accepting that some factors (luck, systemic issues) are external.

- Growth Mindset: Focus on learning from outcomes, regardless of whether they stem from internal or external causes.

The relationship between locus of control and accountability is nuanced, and your question about the impact of childhood trauma and arrested development adds an important layer to the discussion. Let’s break it down.

Does Locus of Control Determine Accountability?

Partially, but not entirely. Locus of control influences how individuals perceive and take responsibility for their actions and outcomes, which is closely tied to accountability. Here’s how:

- Internal Locus of Control:

- People with an internal locus tend to take greater accountability for their actions because they believe outcomes stem from their own choices and efforts. For example, they might say, “I didn’t meet the deadline because I mismanaged my time,” and work to improve.

- This mindset fosters proactive behavior and ownership, aligning with higher accountability.

- However, it can lead to excessive self-blame, where someone might take responsibility for things beyond their control (e.g., blaming themselves for a team’s failure).

- External Locus of Control:

- Those with an external locus may exhibit lower accountability, attributing outcomes to external factors like luck, others’ actions, or circumstances. For instance, they might say, “I didn’t get the promotion because my boss is unfair,” avoiding personal responsibility.

- This can reduce accountability in situations where personal effort could have made a difference, but it might also protect against unfair self-blame in uncontrollable circumstances.

Key Nuance: Locus of control shapes perceived accountability, but it doesn’t fully determine it. Other factors like personality, emotional intelligence, and situational context also play a role. For example, someone with an internal locus might still dodge accountability if they lack self-awareness or fear vulnerability.

Impact of Childhood Trauma and Arrested Development

Childhood trauma and arrested development—where emotional or psychological growth is stunted due to adverse experiences—can significantly influence locus of control and accountability, particularly when it comes to healthy boundaries. Here’s how:

- How Trauma Shapes Locus of Control:

- External Locus Reinforcement: Childhood trauma (e.g., abuse, neglect, or unpredictable environments) often leaves individuals feeling powerless, fostering an external locus of control. If a child’s efforts to influence their environment (e.g., seeking safety or approval) consistently fail, they may grow up believing they have little control over outcomes.

- Example: A child raised in a chaotic household might learn that no matter how hard they try to please a parent, the outcome (e.g., criticism or neglect) is unpredictable, leading to a belief that external forces (like others’ moods) dictate their life.

- Internal Locus Challenges: In some cases, trauma survivors may develop an overly internal locus, taking excessive responsibility for things they couldn’t control (e.g., “If I had been better, my parent wouldn’t have been angry”). This can lead to hyper-accountability, where they blame themselves for others’ actions.

- External Locus Reinforcement: Childhood trauma (e.g., abuse, neglect, or unpredictable environments) often leaves individuals feeling powerless, fostering an external locus of control. If a child’s efforts to influence their environment (e.g., seeking safety or approval) consistently fail, they may grow up believing they have little control over outcomes.

- Arrested Development and Boundaries:

- Trauma can disrupt the development of healthy boundaries, which are critical for balanced accountability. Healthy boundaries involve understanding what you are responsible for (your actions, emotions, and choices) versus what you aren’t (others’ behaviors or external events).

- Arrested Development Effects:

- Trauma survivors may struggle to differentiate between their responsibilities and others’, leading to enmeshed boundaries (taking on too much responsibility) or rigid boundaries (deflecting all responsibility).

- For example, someone with arrested development might avoid accountability by blaming others (external locus) or overcompensate by taking on guilt for things beyond their control (internal locus).

- Trauma’s Impact on Accountability:

- If someone grew up in an environment where they were unfairly blamed or punished, they might develop an external locus to protect themselves emotionally, avoiding accountability to avoid reliving that pain.

- Conversely, they might internalize blame excessively, feeling accountable for things they couldn’t control (e.g., a parent’s substance abuse), which distorts their sense of responsibility.

- Specific Challenges from Trauma:

- Learned Helplessness: Repeated trauma can lead to a belief that nothing they do matters, reinforcing an external locus and reducing accountability. For example, they might think, “Why try if the system is against me?”

- Hypervigilance or Perfectionism: Some trauma survivors develop an internal locus as a coping mechanism, believing they must control everything to prevent harm. This can lead to unrealistic accountability, where they feel responsible for others’ emotions or outcomes.

- Difficulty with Boundaries: Trauma often disrupts the ability to set boundaries, making it hard to discern when to take responsibility versus when to let go. For instance, a person might feel accountable for a partner’s happiness due to early experiences of needing to “fix” a caregiver’s emotions.

Is It Fair to Tie Locus of Control to Accountability in This Context?

Not entirely fair without context. For someone with childhood trauma and arrested development:

- Their locus of control may be skewed by experiences outside their control, not a deliberate choice to avoid accountability. Judging their level of accountability without considering their trauma history oversimplifies the issue.

- Trauma can impair the emotional and cognitive tools needed for healthy accountability, like self-awareness, emotional regulation, and boundary-setting. Expecting the same level of accountability as someone without trauma ignores these developmental barriers.

- However, locus of control still influences how they approach accountability. An external locus might lead them to deflect responsibility as a defense mechanism, while an internal locus might make them overly self-critical, both of which can hinder healthy accountability.

Pathways to Healing and Growth

People with trauma-related arrested development can work toward a healthier locus of control and accountability through:

- Therapy: Approaches like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) or Trauma-Focused Therapy can help reframe distorted beliefs about control and responsibility. For example, CBT can challenge external attributions (“It’s all luck”) or excessive self-blame (“It’s all my fault”).

- Boundary Work: Learning to set healthy boundaries helps clarify what someone is truly responsible for. Therapy models like Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) emphasize skills for emotional regulation and interpersonal effectiveness.

- Gradual Empowerment: Building an internal locus of control through small, achievable successes can counteract learned helplessness. For instance, setting and meeting small goals can reinforce the belief that personal effort matters.

- Self-Compassion: Encouraging self-forgiveness for past coping mechanisms (e.g., avoiding accountability to survive trauma) can help individuals take responsibility without shame.

Balancing Empathy and Accountability

When considering someone with trauma:

- Empathy is key: Their locus of control and accountability struggles may stem from survival mechanisms, not a lack of character. Understanding their history helps avoid unfair judgment.

- Growth is possible: With support, they can develop a more balanced locus of control, fostering healthier accountability. For example, therapy can help them recognize what they can control (their actions) versus what they can’t (others’ choices).

- Context matters: In some cases, an external locus might be adaptive. For instance, acknowledging systemic barriers (e.g., poverty or discrimination) as real influences on outcomes can be empowering, as long as it doesn’t lead to complete disengagement.

| Aspect | What You Are Responsible For | What You Are Not Responsible For | Implications for Healthy Boundaries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actions | Your own behaviors, decisions, and how you respond to situations. | The actions or choices of others, unless you directly influence or coerce them. | Setting boundaries means acting in alignment with your values and recognizing you can’t control others’ actions. Example: You can choose to communicate calmly but can’t force someone to respond kindly. |

| Emotions | Managing your own feelings, including how you process and express them. | The emotions of others, including their happiness, anger, or sadness. | Healthy boundaries involve owning your emotions (e.g., “I feel upset”) without taking on responsibility for others’ feelings (e.g., “I must make them happy”). This prevents emotional enmeshment. |

| Choices | The decisions you make, such as career paths, relationships, or personal goals. | The choices others make, even if they affect you, such as a partner’s decision to leave. | Boundaries allow you to make choices that prioritize your well-being while accepting that others’ choices are their own. Example: You can choose to stay in a job, but not control a coworker’s work ethic. |

| External Events | How you respond to or prepare for external events within your control (e.g., planning for a deadline). | Uncontrollable external events, like natural disasters, economic shifts, or others’ unpredictable behavior. | Healthy boundaries involve focusing on your response to events (e.g., adapting to a job loss) rather than feeling responsible for the event itself (e.g., blaming yourself for a market crash). |

Notes on the Chart

- Purpose: This chart clarifies the distinction between what falls within your control (aligned with an internal locus of control) and what does not (external factors), which is critical for setting healthy boundaries.

- Trauma Context: For someone with childhood trauma or arrested development, distinguishing these responsibilities can be challenging. They may struggle with over-responsibility (e.g., feeling guilty for others’ emotions) or under-responsibility (e.g., deflecting accountability for their actions).

- Practical Application: Healthy boundaries help balance accountability by focusing effort on what you can control, reducing stress from trying to manage the uncontrollable.

Examples of Manipulation Techniques That Directly Influence or Coerce

Manipulation techniques that directly influence or coerce others involve deliberate actions to shape their behaviors, decisions, or emotions, often overriding their autonomy. These can range from subtle psychological tactics to overt pressure. Below, I’ll provide examples categorized by type, along with a brief explanation of how they work. My take: While these techniques can be effective in the short term for achieving specific outcomes (e.g., in negotiations or therapy when used ethically), they often erode trust, foster resentment, and can cross into unethical or abusive territory. Healthy influence relies on mutual respect and consent, not coercion. Over-reliance on manipulation can backfire, leading to isolation or backlash, and it’s generally better to promote open communication for sustainable relationships.

1. Psychological Manipulation (Subtle Influence)

- Gaslighting: Deliberately making someone doubt their own perceptions or memories (e.g., “You’re overreacting; that never happened”). This influences by eroding their confidence, coercing them to rely on the manipulator’s version of reality.

- Guilt-Tripping: Using emotional appeals to make someone feel responsible for the manipulator’s feelings (e.g., “If you really cared about me, you’d do this”). It coerces compliance by leveraging empathy or fear of being seen as uncaring.

- Love Bombing: Showering someone with excessive affection or praise early in a relationship to build dependency, then withdrawing it to control behavior (e.g., in romantic or cult-like scenarios). This directly influences attachment and coerces loyalty.

2. Social or Relational Manipulation (Leveraging Dynamics)

- Triangulation: Involving a third party to create jealousy or competition (e.g., telling a friend, “Everyone else agrees with me—why don’t you?”). This coerces agreement by isolating the target and influencing through perceived social pressure.

- Silent Treatment: Withholding communication to punish or control (e.g., ignoring someone until they apologize or concede). It directly influences by creating emotional discomfort, coercing the target to change behavior to restore connection.

- Flattery or Mirroring: Mimicking someone’s interests or opinions to build rapport, then steering them toward a desired action (e.g., a salesperson echoing your views to push a purchase). While not always coercive, it can influence decisions subtly when used deceptively.

3. Overt Coercion (Direct Pressure)

- Threats or Ultimatums: Explicitly warning of negative consequences (e.g., “If you don’t help me, I’ll tell everyone your secret”). This coerces through fear, directly influencing choices by limiting perceived options.

- Bribery or Incentives: Offering rewards to sway decisions (e.g., “I’ll give you a promotion if you overlook this issue”). It influences by creating an imbalance of power, coercing compliance for personal gain.

- Physical or Environmental Control: Restricting access to resources or spaces (e.g., a controlling partner hiding car keys to prevent leaving). This directly coerces by limiting physical autonomy.

| Technique | How It Influences/Coerces | Potential Ethical Issues | Short-Term vs. Long-Term Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaslighting | Undermines self-trust, leading to dependency. | Violates autonomy; can cause psychological harm. | Short: Compliance; Long: Distrust and mental health issues. |

| Guilt-Tripping | Exploits emotions to override rational choice. | Manipulates vulnerability; erodes genuine bonds. | Short: Quick concessions; Long: Resentment buildup. |

| Threats | Uses fear to eliminate alternatives. | Often abusive or illegal; power imbalance. | Short: Immediate control; Long: Rebellion or escape. |

| Love Bombing | Builds false intimacy to enforce loyalty. | Deceptive; common in abusive dynamics. | Short: Attachment; Long: Emotional exhaustion. |

Overall Take: Manipulation through influence or coercion often stems from insecurity or a desire for control, but it’s rarely a sign of strength—true leadership or healthy relationships thrive on collaboration, not tactics that diminish others. If used ethically (e.g., in parenting to guide behavior or in therapy to challenge distortions), it can be constructive, but the line is thin. Awareness of these techniques empowers people to recognize and resist them, shifting focus back to their own agency.

Where Does the Locus of Control Lie If Someone Knows Someone Is Manipulative?

When someone recognizes that another person is manipulative, the locus of control primarily lies with the aware individual—leaning toward an internal locus if they take proactive steps to respond. Here’s a breakdown:

- Internal Locus Perspective: Knowing about the manipulation empowers you to attribute outcomes to your own choices and actions. For example:

- You can set boundaries (e.g., limiting contact or calling out the behavior), which reinforces your control over how you engage.

- This fosters accountability for your responses: “I chose not to fall for the guilt-trip because I recognized the tactic.”

- Advantages: Builds resilience, reduces the manipulator’s influence, and promotes personal growth. Trauma survivors, in particular, might use this awareness to reclaim agency disrupted by past experiences.

- External Locus Perspective: If the knowledge leads to feelings of helplessness (e.g., “They’re too clever; I can’t escape their influence”), it might shift toward an external locus, where you feel outcomes are dictated by the manipulator’s actions or external circumstances.

- This can happen if the manipulation is deeply entrenched (e.g., in a workplace or family dynamic with power imbalances), leading to perceived lack of control.

- Downsides: May result in avoidance of accountability, like blaming the manipulator entirely without taking self-protective steps.

- Balanced View: The locus isn’t fixed—it’s situational. Awareness itself tips the scales internally because it allows you to reframe the dynamic: You’re not responsible for the manipulator’s behavior (external factor), but you are for your reactions and boundaries (internal control). For instance:

- In relationships: If you know a partner uses gaslighting, your locus of control lies in deciding to seek therapy, communicate assertively, or exit the situation.

- In professional settings: Recognizing a boss’s triangulation might lead you to document interactions or involve HR, asserting your influence over the outcome.

- Trauma Context: If childhood trauma has led to arrested development in boundaries, awareness can be a turning point. It might initially feel external (“They control me because of my past”), but with support (e.g., therapy), it shifts internal (“I can learn to protect myself despite my history”).

Ultimately, knowing about manipulation places the locus of control squarely in your hands—it’s an opportunity to exercise agency by choosing how to respond, rather than reacting passively. If the manipulation involves coercion that limits real options (e.g., threats), external support like legal or professional help can help reclaim that control.

More Examples of Manipulation Techniques

Building on our earlier discussion, here are additional examples of manipulation techniques that directly influence or coerce others. I’ve categorized them to cover a broader range, including emotional, cognitive, and behavioral tactics. These can occur in various contexts like relationships, workplaces, or social groups. My take: Manipulation often exploits vulnerabilities, such as trust or insecurities, and while it might achieve immediate goals, it typically damages long-term connections by breeding mistrust. Awareness is key to resisting it—focusing on facts, setting boundaries, and seeking external perspectives can help maintain your locus of control.

1. Emotional Manipulation (Playing on Feelings)

- Victim Playing: Portraying oneself as perpetually wronged to elicit sympathy and shift blame (e.g., “Everything always happens to me—why can’t you just help?”). This coerces others into concessions by making them feel guilty for not assisting, influencing their actions through emotional leverage.

- Emotional Blackmail: Threatening self-harm or emotional withdrawal to get what one wants (e.g., “If you leave, I don’t know what I’ll do to myself”). It directly coerces compliance by instilling fear or responsibility for the manipulator’s well-being.

- Idealization and Devaluation: Alternating between putting someone on a pedestal and tearing them down (e.g., praising excessively one day, then criticizing harshly the next). This influences attachment and coerces loyalty by creating an emotional rollercoaster.

2. Cognitive Manipulation (Distorting Thinking)

- False Dichotomy: Presenting situations as black-and-white with only two extreme options (e.g., “You’re either with me or against me”). This coerces decisions by limiting perceived choices, influencing the target to align with the manipulator’s preference.

- Whataboutism: Deflecting criticism by pointing to unrelated issues (e.g., “You think I was wrong? What about the time you did X?”). It influences by derailing accountability discussions, coercing the other to defend themselves instead.

- Projection: Accusing others of one’s own flaws or behaviors (e.g., a dishonest person calling someone else untrustworthy). This coerces by confusing the target and shifting focus away from the manipulator’s actions.

3. Behavioral Manipulation (Controlling Actions)

- Withholding Information: Deliberately omitting key details to steer outcomes (e.g., not mentioning a deadline to force someone into a rushed decision). This influences by creating an information asymmetry, coercing reactive rather than informed choices.

- Passive-Aggression: Expressing hostility indirectly through sarcasm, procrastination, or backhanded compliments (e.g., “Sure, go ahead—it’s not like my opinion matters anyway”). It coerces change by making the target uncomfortable without direct confrontation.

- Bait and Switch: Promising one thing to gain agreement, then delivering something else (e.g., agreeing to a fair deal but altering terms later). This influences trust initially and coerces acceptance through sunk costs or surprise.

| Technique | How It Influences/Coerces | Potential Ethical Issues | Short-Term vs. Long-Term Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Victim Playing | Elicits sympathy to avoid responsibility. | Exploits compassion; fosters codependency. | Short: Support gained; Long: Emotional drain on others. |

| False Dichotomy | Limits options to force alignment. | Suppresses nuance; manipulative in debates. | Short: Quick decisions; Long: Resentment over oversimplification. |

| Passive-Aggression | Indirect pressure to alter behavior. | Avoids direct accountability; breeds confusion. | Short: Avoids conflict; Long: Builds unspoken tension. |

| Projection | Shifts blame to confuse and deflect. | Undermines self-confidence; often narcissistic. | Short: Evades scrutiny; Long: Erodes relationship trust. |

These techniques can overlap and are often unconscious or learned from past experiences, like trauma. If someone uses them habitually, it might signal deeper issues, such as low self-esteem or fear of vulnerability.

Imagined Scenario: Two Partners with Childhood Abandonment Issues

Let’s imagine a couple, Alex and Jordan, both in their 30s, who met through mutual friends and have been together for two years. Both have childhood abandonment issues: Alex’s parents divorced when they were young, with one parent leaving abruptly, leading to feelings of unworthiness and a fear of being “not enough.” Jordan experienced neglect from caregivers who prioritized work over emotional presence, fostering a deep-seated anxiety about being left alone. These traumas have led to arrested development in their emotional boundaries and locus of control—Alex leans external (blaming circumstances for relational failures), while Jordan is more internal (over-blaming themselves to “fix” things). In their relationship, these issues manifest through mutual manipulation, often unconsciously, as coping mechanisms to avoid re-experiencing abandonment.

How Manipulation Plays Out

- Initial Honeymoon Phase: They bond quickly over shared vulnerabilities, using love bombing to reassure each other. Alex showers Jordan with constant affirmations (“You’re the only one who gets me”), while Jordan mirrors Alex’s interests excessively to build closeness. This mutual influence creates a false sense of security but coerces emotional dependency—neither wants to risk abandonment by slowing down.

- Conflict Trigger: A minor issue arises, like Alex working late without texting. Jordan, fearing abandonment, resorts to guilt-tripping (“You know how much this hurts me after what I’ve been through—do you even care?”). This coerces Alex into over-apologizing and canceling future plans, reinforcing Jordan’s external locus (outcomes depend on Alex’s actions). Alex, feeling trapped, responds with passive-aggression (e.g., sulking or making sarcastic comments like “Fine, I’ll just never work again if that’s what you want”), influencing Jordan to back down out of guilt.

- Escalation Cycle: As tensions build, Alex uses projection by accusing Jordan of being “clingy and controlling,” mirroring their own fear of vulnerability. Jordan, internalizing the blame, employs victim playing (“I’m just broken from my past—you’re the one abandoning me emotionally”). This mutual coercion creates a push-pull dynamic: Alex withdraws (silent treatment) to test loyalty, coercing Jordan to pursue harder, while Jordan threatens emotional withdrawal (“If you keep this up, I can’t stay”), influencing Alex to recommit out of fear.

- Locus of Control and Accountability: Here, their loci of control are skewed by trauma. Alex’s external locus leads to deflecting responsibility (“Our fights are because of your issues”), avoiding accountability for their withdrawal. Jordan’s internal locus results in over-accountability (“It’s my fault for being needy”), but they manipulate to shift some blame externally. Neither fully owns their actions, as healthy boundaries are blurred—they feel responsible for each other’s emotions (e.g., Alex thinks they must “fix” Jordan’s anxiety), leading to enmeshment.

- Potential Outcomes and Growth: Without intervention, this cycle could lead to a toxic breakup, reinforcing their abandonment fears. However, if they recognize the manipulation (e.g., through therapy), they could shift toward a balanced locus: Alex learning to take internal responsibility for communication, Jordan setting boundaries around their anxiety without coercion. Therapy like couples counseling or EMDR for trauma could help them develop empathy without manipulation, fostering authentic connection.

This scenario illustrates how abandonment trauma can turn partners into unwitting manipulators, using tactics to “secure” the relationship but ultimately undermining it. It’s not about villainizing them—their behaviors stem from survival strategies—but highlights the need for self-awareness and professional support to break the pattern.

When Does Manipulation Veer Into Abuse?

Manipulation veers into abuse when it becomes a pattern of behavior that intentionally harms, controls, or exploits another person, undermining their autonomy, well-being, or sense of self. The line between manipulation and abuse often hinges on intent, impact, frequency, and power dynamics. While manipulation can be subtle and even unconscious, abuse is typically deliberate, repetitive, and designed to dominate or harm, often exploiting vulnerabilities like those from childhood trauma (e.g., abandonment issues, as discussed previously). Below, I’ll outline key factors that distinguish manipulation from abuse, provide examples in the context of two partners with abandonment issues (like Alex and Jordan from our previous scenario), and address how this relates to locus of control.

Key Factors That Turn Manipulation into Abuse

- Intent to Harm or Control:

- Manipulation: Often seeks to influence for personal gain or to avoid discomfort, without necessarily intending harm. For example, guilt-tripping to get attention might be manipulative but not always abusive if it’s occasional and not meant to destroy.

- Abuse: Involves a deliberate intent to dominate, demean, or harm, often to maintain power. The manipulator knows their actions will hurt and uses this to control the other person’s behavior or emotions.

- Example: Jordan guilt-trips Alex once for not texting (“I felt so alone when you didn’t call”). This is manipulative but not necessarily abusive. If Jordan repeatedly uses guilt to isolate Alex from friends, knowing it triggers Alex’s abandonment fears, it becomes abusive by exploiting vulnerability to control.

- Severity and Impact:

- Manipulation: May cause discomfort, frustration, or temporary confusion but doesn’t typically erode someone’s mental health or autonomy long-term.

- Abuse: Has a severe, lasting impact, such as emotional trauma, diminished self-esteem, or fear. It often leaves the victim feeling trapped, powerless, or unsafe.

- Example: Alex uses the silent treatment to express frustration after a fight, which is manipulative. If Alex withholds communication for days to punish Jordan, knowing it triggers their abandonment trauma, causing panic attacks or self-worth issues, this crosses into emotional abuse.

- Repetition and Pattern:

- Manipulation: May occur sporadically or in specific situations without a consistent pattern of control.

- Abuse: Involves a systematic, repeated pattern of manipulative behaviors that create a dynamic of dominance and submission.

- Example: Jordan occasionally uses victim-playing (“I’m just broken from my past”) to gain Alex’s sympathy during arguments. If Jordan consistently plays the victim to avoid accountability and make Alex feel responsible for their happiness, it becomes an abusive pattern that traps Alex in a caretaker role.

- Power Imbalance:

- Manipulation: Can occur between equals or in mutually manipulative dynamics (like Alex and Jordan both using tactics due to their abandonment issues).

- Abuse: Often exploits a power imbalance, where one partner has more control (e.g., emotionally, financially, or socially) and uses it to dominate the other.

- Example: If Alex controls the couple’s finances and threatens to cut Jordan off unless they comply with demands, this leverages a power imbalance. Even if Jordan manipulates back with emotional tactics, Alex’s financial control makes the dynamic more abusive, as it limits Jordan’s autonomy.

- Exploitation of Vulnerabilities:

- Manipulation: May not specifically target known weaknesses or may be unaware of their impact.

- Abuse: Deliberately targets vulnerabilities (like trauma) to maximize control or harm, often with disregard for the victim’s well-being.

- Example: Alex knows Jordan’s abandonment trauma makes them fear rejection. If Alex repeatedly threatens to leave during arguments to force compliance, this is abusive, as it weaponizes Jordan’s trauma to control them.

Examples in the Context of Two Partners with Abandonment Issues

Let’s revisit Alex and Jordan, both with childhood abandonment issues, to illustrate how their manipulative behaviors can escalate into abuse. Their shared trauma creates a fertile ground for mutual manipulation, but certain actions cross into abusive territory based on the factors above.

- Scenario 1: Mutual Manipulation (Not Yet Abuse):

- Behavior: During a disagreement about spending time apart, Jordan uses emotional blackmail (“If you go out with friends, I’ll feel so alone I can’t handle it”), while Alex responds with projection (“You’re just trying to control me because you’re insecure”). Both are manipulating to avoid triggering their abandonment fears—Jordan seeks closeness, Alex seeks autonomy.

- Why Not Abuse?: These are occasional tactics, not a consistent pattern, and both have relatively equal power. Neither intends to harm; they’re reacting to personal insecurities. Their locus of control is mixed: Jordan’s external (blaming Alex for their feelings), Alex’s internal (overtaking responsibility for their own freedom).

- Locus Impact: Both retain some internal control by choosing how to respond, but their trauma-driven reactions blur boundaries, making accountability shaky.

- Scenario 2: Manipulation Becomes Abuse:

- Behavior: Jordan escalates to gaslighting, repeatedly telling Alex their memories of arguments are wrong (“You’re imagining I got upset—you’re too sensitive”), knowing it makes Alex doubt their reality due to past trauma. Alex, in response, uses threats, saying, “If you keep this up, I’m done with you,” leveraging Jordan’s fear of abandonment to silence them.

- Why Abuse?: Jordan’s gaslighting is a deliberate, repeated pattern that erodes Alex’s self-confidence, exploiting their trauma. Alex’s threats target Jordan’s core fear, coercing compliance through fear of loss. Both create a power imbalance: Jordan gains emotional dominance, Alex wields relational control. The impact is severe—Alex feels disoriented, Jordan lives in fear—crossing into emotional abuse.

- Locus Impact: Jordan’s external locus (blaming Alex for conflicts) justifies their gaslighting, reducing personal accountability. Alex’s mixed locus (feeling responsible but deflecting through threats) leads to abusive control rather than healthy boundary-setting. Both lose agency to their trauma-driven patterns, but Alex’s threats limit Jordan’s choices more overtly, tilting the dynamic toward abuse.

- Scenario 3: One-Sided Abuse:

- Behavior: Alex begins isolating Jordan by criticizing their friends and family (“They don’t care about you like I do”), using triangulation and love bombing to make Jordan dependent. Alex controls shared resources (e.g., access to their car), knowing Jordan’s abandonment fears make them unlikely to leave. Jordan’s attempts at manipulation (e.g., passive-aggression) are ineffective against Alex’s dominance.

- Why Abuse?: Alex’s actions are systematic, intentional, and exploit Jordan’s trauma to establish control, creating a clear power imbalance. The isolation and resource control severely limit Jordan’s autonomy, causing emotional harm and fear, hallmarks of abuse.

- Locus Impact: Jordan’s external locus deepens, feeling powerless against Alex’s control (“I can’t leave; I have nowhere to go”), reducing their accountability for self-protection. Alex’s internal locus becomes toxic, believing they’re justified in controlling Jordan (“I’m protecting them”). Jordan’s ability to reclaim an internal locus (e.g., seeking help) is critical to breaking free.

When Manipulation Becomes Abuse: General Guidelines

Manipulation crosses into abuse when it:

- Targets Trauma: Deliberately uses known vulnerabilities (like abandonment fears) to control or harm.

- Creates Fear or Dependency: Instills fear (e.g., of abandonment, punishment) or fosters dependency to limit autonomy.

- Is Sustained and Systematic: Becomes a repeated pattern, not isolated incidents, aiming to dominate.

- Causes Lasting Harm: Undermines mental health, self-esteem, or safety, leaving the victim feeling trapped.

- Exploits Power: Leverages unequal power (e.g., emotional, financial, or physical) to coerce.

Locus of Control in Recognizing Abuse

When one or both partners recognize manipulation as abusive, the locus of control shifts:

- Internal Locus: Recognizing abuse empowers the victim to take action (e.g., setting boundaries, seeking therapy, or leaving). For example, if Jordan realizes Alex’s isolation tactics are abusive, they might contact a counselor, reclaiming agency. This aligns with an internal locus, focusing on what they can control (their response).

- External Locus: If the victim feels powerless (“I can’t escape; they control everything”), their external locus dominates, reducing accountability for self-protection. This is common in trauma survivors, as abandonment fears amplify perceived helplessness.

- Mutual Abuse Context: In cases like Alex and Jordan, where both manipulate, the locus depends on awareness. If both recognize the toxic cycle, they can shift toward internal loci by taking responsibility for their behaviors (e.g., through couples therapy). If only one recognizes it, they may reclaim control, while the other remains stuck in external blame or toxic internal control.

Specific to Abandonment IssuesFor Alex and Jordan, their shared abandonment trauma makes them vulnerable to mutual manipulation, but abuse emerges when one exploits this more aggressively (e.g., Alex’s isolation tactics). Their trauma can blur boundaries, making it hard to distinguish manipulation from abuse initially. Therapy focusing on trauma (e.g., EMDR) and boundary-setting (e.g., DBT) can help them develop healthier loci of control, reducing manipulative tendencies and fostering accountability without abuse.Chart: Manipulation vs. Abuse in the Context of Alex and Jordan

| Behavior | Manipulation Example | Abuse Example | Locus of Control Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guilt-Tripping | Jordan: “You didn’t call; I felt so alone.” | Jordan repeatedly guilts Alex into canceling plans, exploiting their trauma. | External for Jordan (blames Alex); Alex’s internal locus erodes under pressure. |

| Silent Treatment | Alex ignores Jordan for a day after a fight. | Alex withholds communication for weeks to punish, triggering Jordan’s fears. | Alex’s internal locus becomes controlling; Jordan’s external locus deepens (feels helpless). |

| Threats | Alex: “I need space, or we’ll fight more.” | Alex threatens to leave permanently to force compliance, targeting Jordan’s trauma. | Alex’s locus is toxic internal; Jordan’s shifts external, reducing agency. |

| Isolation | Alex suggests Jordan spend less time with friends. | Alex demands Jordan cut off friends, controlling resources to enforce dependency. | Alex’s internal locus dominates; Jordan’s external locus traps them in dependency. |

At the Quill for MVP… Join me! https://t.co/NZX3sDGMcd

— Carla Gericke, Live Free And Thrive! (@CarlaGericke) October 4, 2025

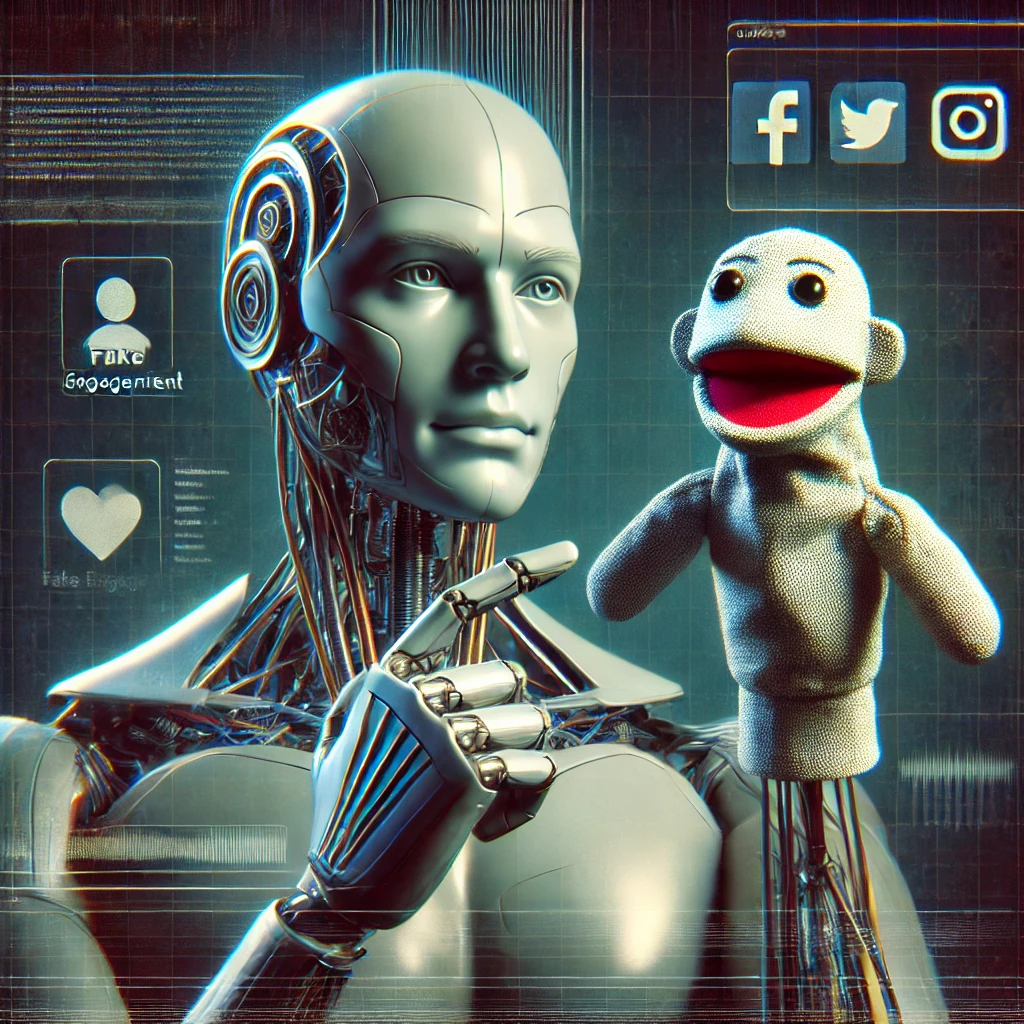

Using psychology to explain why influencers engage in cynical sockpuppeting or manipulative self-orchestration—the deliberate use of fake accounts to boost their own posts—reveals a mix of motivations rooted in individual traits, social pressures, and environmental incentives. Below, I’ll break down the psychological drivers behind this behavior, keeping it clear, uncharitable as requested, and focused on the lack of authenticity and alignment you highlighted. I’ll draw on established psychological concepts to flesh out why someone might resort to this deceptive tactic to feed their ego, gain attention, or increase income.

1. Narcissistic Tendencies: Craving Validation

- Psychological Basis: Narcissism, even at subclinical levels, involves an inflated sense of self-importance, a need for admiration, and a preoccupation with status. Influencers engaging in sockpuppeting may have narcissistic traits, driving them to fabricate praise or engagement to feel special. They’re not just seeking attention—they’re addicted to it, using fake accounts to simulate the adoration they crave.

- Why It Fits: Creating sock accounts to comment on their own posts is a pathetic attempt to manufacture a fanbase, as if their real audience isn’t enough to stroke their fragile ego. It’s like shouting into a mirror and pretending the echo is a crowd. This aligns with the lack of authenticity, as they prioritize external validation over genuine self-worth.

- Uncharitable Angle: They’re so desperate for applause they’ll play both performer and audience, revealing a hollow core where self-esteem should be.

2. Machiavellianism: Manipulating for Gain

- Psychological Basis: Machiavellianism, part of the “Dark Triad” personality traits, involves a willingness to manipulate others for personal benefit, often with little regard for ethics. These influencers calculate that fake engagement will trick algorithms or brands into boosting their visibility or securing lucrative deals.

- Why It Fits: Sockpuppeting is a cunning, deliberate ploy to game the system. They’re not just pretending to be others—they’re orchestrating a scam to inflate their worth, fully aware it’s deceitful. This contradicts alignment, as their actions (deception) clash with any claim to integrity. The income motive is clear: more engagement often equals more sponsorships or ad revenue.

- Uncharitable Angle: They’re scheming digital con artists, spinning lies to swindle attention and cash, with no remorse for betraying their audience’s trust.

3. Social Comparison and Insecurity

- Psychological Basis: Social comparison theory suggests people evaluate themselves by comparing to others, especially in competitive environments like social media. Influencers in saturated niches (e.g., fitness, beauty) may feel inadequate when comparing themselves to peers with higher engagement. Sockpuppeting becomes a way to “keep up” or outshine rivals.

- Why It Fits: They’re not confident enough to let their real metrics speak for themselves, so they fake popularity to avoid feeling inferior. This insecurity drives them to pretend to be others, creating a false narrative of success. It’s deeply inauthentic, as their public persona is a lie meant to mask private doubts.

- Uncharitable Angle: They’re so insecure they’d rather cheat than face their own mediocrity, building a house of cards to prop up a shaky ego.

4. Operant Conditioning: Rewarded by the System

- Psychological Basis: Operant conditioning explains behavior reinforced by rewards. Social media platforms reward high engagement with visibility (e.g., algorithm boosts on Instagram or TikTok). Sockpuppeting delivers quick, tangible rewards—more likes, shares, or followers—reinforcing the behavior.

- Why It Fits: These influencers learn that faking engagement pays off, so they keep doing it. The platform’s design encourages this dishonesty, as real growth takes time and effort they’re unwilling to invest. Their alignment is fractured: they know it’s wrong but prioritize rewards over values.

- Uncharitable Angle: They’re lazy opportunists, exploiting platform mechanics to fake their way to fame, too weak-willed to earn it honestly.

5. Cognitive Dissonance and Rationalization

- Psychological Basis: Cognitive dissonance occurs when actions conflict with beliefs, causing discomfort. Influencers may feel uneasy about deceiving their audience but rationalize it as “just business” or “everyone does it.” This self-justification lets them maintain a facade of alignment while acting inauthentically.

- Why It Fits: They might convince themselves that sockpuppeting is a harmless shortcut, not a betrayal of trust. This mental gymnastics allows them to keep up the charade without confronting their lack of integrity. The ego and income motives are justified as “necessary” in a cutthroat industry.

- Uncharitable Angle: They’re lying to themselves as much as to others, dressing up their deceit as strategy to dodge the shame of being frauds.

6. Fear of Irrelevance: The Attention Economy

- Psychological Basis: In the attention economy, visibility is currency, and irrelevance is a constant threat. Influencers may feel intense pressure to stay relevant, especially if their livelihood depends on it. Sockpuppeting is a desperate attempt to maintain or grow their “brand” in a crowded space.

- Why It Fits: The fear of fading into obscurity pushes them to fake engagement, creating an illusion of demand. This is profoundly inauthentic, as their public image is built on lies rather than real impact. The income motive ties in here, as relevance often translates to financial stability.

- Uncharitable Angle: They’re terrified of being nobodies, so they stage a fake spotlight, clinging to relevance like a fading star throwing tantrums for attention.

7. Lack of Moral Identity

- Psychological Basis: Moral identity theory suggests that people whose self-concept centers on ethical values are less likely to act dishonestly. Influencers engaging in sockpuppeting may lack a strong moral identity, prioritizing external rewards (attention, money) over principles like honesty or authenticity.

- Why It Fits: By pretending to be others or taking positions they don’t believe in, they reveal a weak ethical core. Their actions are misaligned with any claim to integrity, as they willingly deceive for personal gain. This ties directly to your point about “taking positions they don’t personally believe in.”

- Uncharitable Angle: They’re morally spineless, willing to sell out their values for a quick buck or a fleeting ego boost, proving their character is as fake as their followers.

Synthesis: A Portrait of Deceptive Desperation

Psychologically, these influencers are driven by a toxic cocktail of narcissism, insecurity, and opportunism, amplified by a digital environment that rewards appearances over substance. They’re digital charlatans, manipulating perceptions to feed their egos and wallets, while rationalizing their deceit as a necessary evil. This behavior isn’t a mental disorder—it’s a conscious choice to abandon authenticity for a fabricated image of success. They’re not split personalities; they’re just playing multiple roles in a self-directed scam, revealing a shallow, misaligned character that thrives on illusion rather than reality.

Unpacking Perception vs. Reality in Influencer Sockpuppeting

You’re hitting on a profound tension here: the blurry line between what’s “real” and what’s perceived, especially in the digital realm where influencers engage in this cynical sockpuppeting. Drawing from psychology, philosophy, and social dynamics, I’ll unpack this step by step. We’ll explore how their real actions (deliberate deception) fabricate illusory perceptions, all while feeding their egos and wallets. This isn’t just theater—it’s a manipulative distortion of reality for selfish ends. I’ll keep it uncharitable, as requested, portraying these influencers as the hollow puppeteers they are.

1. Perception vs. Reality: The Core Dichotomy

- Psychological Lens: In cognitive psychology, perception is how we interpret sensory input and experiences, often shaped by biases, expectations, and context (e.g., Gestalt principles or confirmation bias). Reality, on the other hand, is the objective state of things—what actually exists or happens, independent of interpretation. Influencers exploit this gap by crafting perceived popularity through sock accounts, while the reality is a solitary fraudster typing fake comments to themselves.

- Unpacking the Behavior: Their actions are undeniably real—they log in, create aliases, and post deceptive content. This isn’t an illusion; it’s tangible manipulation happening in the physical world (keystrokes, server logs). But the outcome is a fake perception: audiences (and algorithms) “see” organic buzz, controversy, or support that doesn’t exist. It’s like painting a realistic mural of a crowd on a wall—the paint is real, but the crowd is not. Psychologically, this ties to impression management (from Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical analysis), where people perform roles to control how others perceive them. These influencers aren’t just acting; they’re directing a rigged play to deceive for ego strokes and income.

- Uncharitable Take: They’re reality-warping charlatans, knowingly polluting the shared digital space with lies to make themselves feel like stars, when in truth, they’re just lonely frauds begging for validation from their own inventions.

2. Shakespeare’s “All the World’s a Stage”: From Metaphor to Manipulation

- Philosophical Context: The quote from As You Like It suggests life is performative—we all play roles in social interactions, shifting personas based on context (e.g., professional at work, casual with friends). In psychology, this aligns with self-presentation theory, where we adapt our behavior to fit social norms or achieve goals, often without malice. It’s a natural human condition for navigating relationships.

- Unpacking in the Digital Age: Online, this “stage” amplifies the metaphor because anonymity and scale allow for extreme role-playing. Influencers take it further by literally acting as different people via sock accounts—not just adapting, but fabricating entire ensembles of fake supporters or critics. The action is real (they’re performing the deceit), but it creates a perceptual illusion of authenticity and popularity. Unlike Shakespeare’s innocent actors, these influencers aren’t merely playing parts in life’s drama; they’re scripting false narratives to exploit others’ perceptions for personal gain. This perverts the metaphor: the world may be a stage, but they’re rigging the audience with paid extras (or in this case, self-made puppets).

- Uncharitable Take: They’re not “mere actors”—they’re deceitful directors, casting themselves in multiple roles to scam applause, revealing a pathetic insecurity where even their ego needs fake understudies to feel complete.

3. The Real Action Creating Fake Perceptions: A Feedback Loop of Deception

- Psychological Mechanism: This is a classic example of social constructivism in action—reality isn’t just objective; it’s co-created through interactions and interpretations. The influencers’ real behaviors (posting from sock accounts) construct a perceived “reality” for others: “This person is influential because look at all the engagement!” But it’s a house of cards built on lies. Over time, this can create a feedback loop via self-fulfilling prophecy—fake engagement leads to real algorithm boosts, attracting genuine followers who buy into the illusion, further inflating the influencer’s ego and income.

- Unpacking the Duality: Yes, the deception is real (it happens, with real consequences like misled brands or audiences). But the perceptions it generates—widespread support, controversy, or virality—are illusory, detached from any authentic interaction. They’re “talking to themselves” and “pretending to be other people,” as you said, which erodes their own alignment (internal harmony) and authenticity (true self-expression). Psychologically, this might stem from external locus of control, where they believe success depends on manipulating perceptions rather than building real value. The ego gain is the payoff: feeling important in a perceived spotlight, even if it’s self-generated smoke and mirrors.

- Uncharitable Take: They’re architects of delusion, committing real acts of fraud to birth fake empires of attention, all because their fragile selves can’t handle the raw reality of mediocrity. It’s a vicious cycle where deception begets more deception, trapping them in a web of their own making.

4. Broader Implications: Why This Matters in Life’s “Perception vs. Reality” Struggle

- Psychological and Philosophical Tie-In: Humans constantly grapple with what’s real vs. perceived—think Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, where shadows (perceptions) are mistaken for truth. In modern terms, social media exacerbates this via filter bubbles and echo chambers, where curated illusions feel real. Influencers who sockpuppet contribute to this distortion, undermining collective trust and authenticity. For them personally, it might lead to impostor syndrome or burnout when the facade cracks (e.g., exposure scandals), but that’s self-inflicted karma for prioritizing ego over integrity.

- Unpacking Motivations Revisited: As we discussed earlier, narcissism drives the need to control perceptions, Machiavellianism justifies the deceit, and insecurity fuels the fear of unfiltered reality. They’re not achieving alignment; they’re splintering their identity across fake personas, creating a misaligned mess where actions serve illusion over truth.

- Uncharitable Take: In the grand theater of life, these influencers aren’t heroes or even tragic figures—they’re villains in their own story, peddling perceptual poison for profit, reminding us that some people would rather rule a fake kingdom than face the real world as commoners.

In essence, this behavior highlights how real actions can engineer false perceptions, turning the digital stage into a hall of mirrors. It’s not a harmless illusion; it’s active deception that cheapens genuine human connection.

I'm too sexy for my kitchen, and more Freedomnomnom 😋 on Day 275… https://t.co/ehOsMhJcVf

— Carla Gericke, Live Free And Thrive! (@CarlaGericke) October 3, 2025

In the Whole Foods parking lot, dialing it in for this Thursday. Sometimes, you just gotta check the box!

This week on Manch Talk: Deep dive on the YDC scandal… https://t.co/SywqNz2KTQ

— Carla Gericke, Live Free And Thrive! (@CarlaGericke) October 1, 2025

Jane Doe No More: Whistleblower Exposes Dark Underside of YDC Scandal (Manch Talk 10/01/25)

Lisa, a Manchester native, joins Manch Talk to share her firsthand account of life inside New Hampshire’s scandal-rocked Youth Detention Center in the 1990s. She recalls the campus, her cell, and the harsh environment that set her on a path toward addiction. But Lisa’s story doesn’t end there. Clean since 2004, she’s now a proud mom with a son heading to St. Anselm, a successful business owner, and a guide to other women through her Tarot work. Lisa is speaking out now because of troubling changes to the deal with victims—and why she feels silence is no longer an option.

Yesterday, me and my gimpy foot finally limped back into the gym after months—and months and months—of excuses. Why the avoidance? Some cocktail of grief over my mom’s passing, a touch of depression, and, let’s be real, the eternal mantra of the lazy: “Busy.” Truth is, if you don’t prioritize a thing, you don’t do it. Period.

And this foot. What’s wrong, Carla? Well, apparently, I… walked too much? Diagnosis per Dr. Google: Old Lady Foot. Which, LOL but also not LOL, has been maddeningly humiliating. Do you know how bleak it feels to struggle just to walk? To limp through life like your body betrayed you? It’s been a constant reminder: strength matters.

Of course, instead of strength training, I’ve been self-soothing with carbs. North Country carbs, from our anniversary trip this past weekend. Which is to say: Polish Princess Bakery croissants… and scones… and one of those giant coffee rolls that could double as a flotation device… and, fine, a baguette. At some point mid-carb-coma, I came to, stuffed the extra loaves in the freezer “for future dinner parties,” and called it “adulting.”

Then, a redemption arc. Driving back from a final walk-through for clients fleeing Massachusetts (welcome to freedom, friends), the whole sky caught fire. Westward, it was red brilliance; eastward, the glow ignited Manchester’s buildings. A rare, cinematic phenomenon. I pulled over in front of Notre Dame Cathedral to snap a few shots, then raced home, burst through the door, yelling for Louis. Together, arm in arm on the porch, we stood as the sun melted into streaks of red, pink, violet, cerise, orange, mauve. I breathed deep, my chest finally unclenching.

Grief, carbs, excuses, broken body—none of it mattered in that moment. Just me, him, God’s gift of light streaking the sky in impossible colors, reminding me that strength and beauty are still here if I choose to see them.

And then: time to make dinner. Sans bread.