Using psychology to explain why influencers engage in cynical sockpuppeting or manipulative self-orchestration—the deliberate use of fake accounts to boost their own posts—reveals a mix of motivations rooted in individual traits, social pressures, and environmental incentives. Below, I’ll break down the psychological drivers behind this behavior, keeping it clear, uncharitable as requested, and focused on the lack of authenticity and alignment you highlighted. I’ll draw on established psychological concepts to flesh out why someone might resort to this deceptive tactic to feed their ego, gain attention, or increase income.

1. Narcissistic Tendencies: Craving Validation

- Psychological Basis: Narcissism, even at subclinical levels, involves an inflated sense of self-importance, a need for admiration, and a preoccupation with status. Influencers engaging in sockpuppeting may have narcissistic traits, driving them to fabricate praise or engagement to feel special. They’re not just seeking attention—they’re addicted to it, using fake accounts to simulate the adoration they crave.

- Why It Fits: Creating sock accounts to comment on their own posts is a pathetic attempt to manufacture a fanbase, as if their real audience isn’t enough to stroke their fragile ego. It’s like shouting into a mirror and pretending the echo is a crowd. This aligns with the lack of authenticity, as they prioritize external validation over genuine self-worth.

- Uncharitable Angle: They’re so desperate for applause they’ll play both performer and audience, revealing a hollow core where self-esteem should be.

2. Machiavellianism: Manipulating for Gain

- Psychological Basis: Machiavellianism, part of the “Dark Triad” personality traits, involves a willingness to manipulate others for personal benefit, often with little regard for ethics. These influencers calculate that fake engagement will trick algorithms or brands into boosting their visibility or securing lucrative deals.

- Why It Fits: Sockpuppeting is a cunning, deliberate ploy to game the system. They’re not just pretending to be others—they’re orchestrating a scam to inflate their worth, fully aware it’s deceitful. This contradicts alignment, as their actions (deception) clash with any claim to integrity. The income motive is clear: more engagement often equals more sponsorships or ad revenue.

- Uncharitable Angle: They’re scheming digital con artists, spinning lies to swindle attention and cash, with no remorse for betraying their audience’s trust.

3. Social Comparison and Insecurity

- Psychological Basis: Social comparison theory suggests people evaluate themselves by comparing to others, especially in competitive environments like social media. Influencers in saturated niches (e.g., fitness, beauty) may feel inadequate when comparing themselves to peers with higher engagement. Sockpuppeting becomes a way to “keep up” or outshine rivals.

- Why It Fits: They’re not confident enough to let their real metrics speak for themselves, so they fake popularity to avoid feeling inferior. This insecurity drives them to pretend to be others, creating a false narrative of success. It’s deeply inauthentic, as their public persona is a lie meant to mask private doubts.

- Uncharitable Angle: They’re so insecure they’d rather cheat than face their own mediocrity, building a house of cards to prop up a shaky ego.

4. Operant Conditioning: Rewarded by the System

- Psychological Basis: Operant conditioning explains behavior reinforced by rewards. Social media platforms reward high engagement with visibility (e.g., algorithm boosts on Instagram or TikTok). Sockpuppeting delivers quick, tangible rewards—more likes, shares, or followers—reinforcing the behavior.

- Why It Fits: These influencers learn that faking engagement pays off, so they keep doing it. The platform’s design encourages this dishonesty, as real growth takes time and effort they’re unwilling to invest. Their alignment is fractured: they know it’s wrong but prioritize rewards over values.

- Uncharitable Angle: They’re lazy opportunists, exploiting platform mechanics to fake their way to fame, too weak-willed to earn it honestly.

5. Cognitive Dissonance and Rationalization

- Psychological Basis: Cognitive dissonance occurs when actions conflict with beliefs, causing discomfort. Influencers may feel uneasy about deceiving their audience but rationalize it as “just business” or “everyone does it.” This self-justification lets them maintain a facade of alignment while acting inauthentically.

- Why It Fits: They might convince themselves that sockpuppeting is a harmless shortcut, not a betrayal of trust. This mental gymnastics allows them to keep up the charade without confronting their lack of integrity. The ego and income motives are justified as “necessary” in a cutthroat industry.

- Uncharitable Angle: They’re lying to themselves as much as to others, dressing up their deceit as strategy to dodge the shame of being frauds.

6. Fear of Irrelevance: The Attention Economy

- Psychological Basis: In the attention economy, visibility is currency, and irrelevance is a constant threat. Influencers may feel intense pressure to stay relevant, especially if their livelihood depends on it. Sockpuppeting is a desperate attempt to maintain or grow their “brand” in a crowded space.

- Why It Fits: The fear of fading into obscurity pushes them to fake engagement, creating an illusion of demand. This is profoundly inauthentic, as their public image is built on lies rather than real impact. The income motive ties in here, as relevance often translates to financial stability.

- Uncharitable Angle: They’re terrified of being nobodies, so they stage a fake spotlight, clinging to relevance like a fading star throwing tantrums for attention.

7. Lack of Moral Identity

- Psychological Basis: Moral identity theory suggests that people whose self-concept centers on ethical values are less likely to act dishonestly. Influencers engaging in sockpuppeting may lack a strong moral identity, prioritizing external rewards (attention, money) over principles like honesty or authenticity.

- Why It Fits: By pretending to be others or taking positions they don’t believe in, they reveal a weak ethical core. Their actions are misaligned with any claim to integrity, as they willingly deceive for personal gain. This ties directly to your point about “taking positions they don’t personally believe in.”

- Uncharitable Angle: They’re morally spineless, willing to sell out their values for a quick buck or a fleeting ego boost, proving their character is as fake as their followers.

Synthesis: A Portrait of Deceptive Desperation

Psychologically, these influencers are driven by a toxic cocktail of narcissism, insecurity, and opportunism, amplified by a digital environment that rewards appearances over substance. They’re digital charlatans, manipulating perceptions to feed their egos and wallets, while rationalizing their deceit as a necessary evil. This behavior isn’t a mental disorder—it’s a conscious choice to abandon authenticity for a fabricated image of success. They’re not split personalities; they’re just playing multiple roles in a self-directed scam, revealing a shallow, misaligned character that thrives on illusion rather than reality.

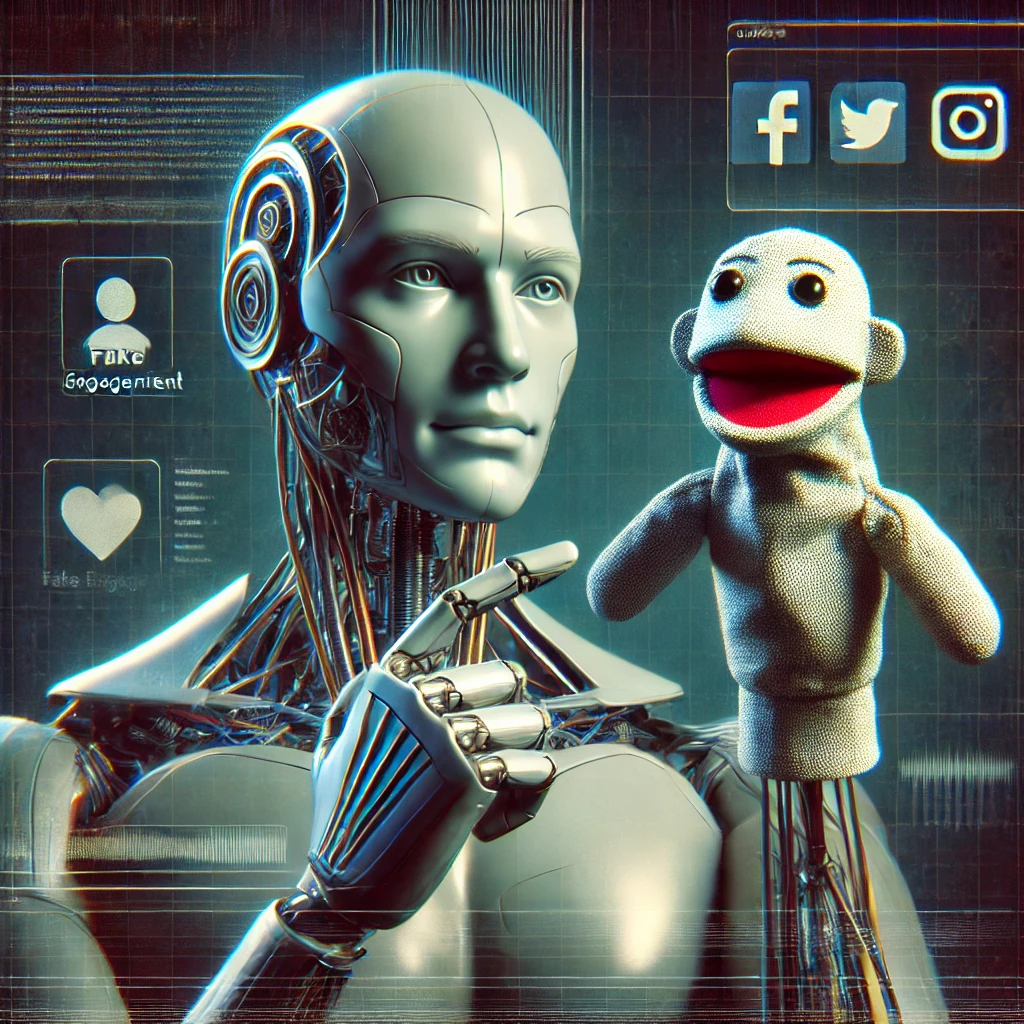

Unpacking Perception vs. Reality in Influencer Sockpuppeting

You’re hitting on a profound tension here: the blurry line between what’s “real” and what’s perceived, especially in the digital realm where influencers engage in this cynical sockpuppeting. Drawing from psychology, philosophy, and social dynamics, I’ll unpack this step by step. We’ll explore how their real actions (deliberate deception) fabricate illusory perceptions, all while feeding their egos and wallets. This isn’t just theater—it’s a manipulative distortion of reality for selfish ends. I’ll keep it uncharitable, as requested, portraying these influencers as the hollow puppeteers they are.

1. Perception vs. Reality: The Core Dichotomy

- Psychological Lens: In cognitive psychology, perception is how we interpret sensory input and experiences, often shaped by biases, expectations, and context (e.g., Gestalt principles or confirmation bias). Reality, on the other hand, is the objective state of things—what actually exists or happens, independent of interpretation. Influencers exploit this gap by crafting perceived popularity through sock accounts, while the reality is a solitary fraudster typing fake comments to themselves.

- Unpacking the Behavior: Their actions are undeniably real—they log in, create aliases, and post deceptive content. This isn’t an illusion; it’s tangible manipulation happening in the physical world (keystrokes, server logs). But the outcome is a fake perception: audiences (and algorithms) “see” organic buzz, controversy, or support that doesn’t exist. It’s like painting a realistic mural of a crowd on a wall—the paint is real, but the crowd is not. Psychologically, this ties to impression management (from Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical analysis), where people perform roles to control how others perceive them. These influencers aren’t just acting; they’re directing a rigged play to deceive for ego strokes and income.

- Uncharitable Take: They’re reality-warping charlatans, knowingly polluting the shared digital space with lies to make themselves feel like stars, when in truth, they’re just lonely frauds begging for validation from their own inventions.

2. Shakespeare’s “All the World’s a Stage”: From Metaphor to Manipulation

- Philosophical Context: The quote from As You Like It suggests life is performative—we all play roles in social interactions, shifting personas based on context (e.g., professional at work, casual with friends). In psychology, this aligns with self-presentation theory, where we adapt our behavior to fit social norms or achieve goals, often without malice. It’s a natural human condition for navigating relationships.

- Unpacking in the Digital Age: Online, this “stage” amplifies the metaphor because anonymity and scale allow for extreme role-playing. Influencers take it further by literally acting as different people via sock accounts—not just adapting, but fabricating entire ensembles of fake supporters or critics. The action is real (they’re performing the deceit), but it creates a perceptual illusion of authenticity and popularity. Unlike Shakespeare’s innocent actors, these influencers aren’t merely playing parts in life’s drama; they’re scripting false narratives to exploit others’ perceptions for personal gain. This perverts the metaphor: the world may be a stage, but they’re rigging the audience with paid extras (or in this case, self-made puppets).

- Uncharitable Take: They’re not “mere actors”—they’re deceitful directors, casting themselves in multiple roles to scam applause, revealing a pathetic insecurity where even their ego needs fake understudies to feel complete.

3. The Real Action Creating Fake Perceptions: A Feedback Loop of Deception

- Psychological Mechanism: This is a classic example of social constructivism in action—reality isn’t just objective; it’s co-created through interactions and interpretations. The influencers’ real behaviors (posting from sock accounts) construct a perceived “reality” for others: “This person is influential because look at all the engagement!” But it’s a house of cards built on lies. Over time, this can create a feedback loop via self-fulfilling prophecy—fake engagement leads to real algorithm boosts, attracting genuine followers who buy into the illusion, further inflating the influencer’s ego and income.

- Unpacking the Duality: Yes, the deception is real (it happens, with real consequences like misled brands or audiences). But the perceptions it generates—widespread support, controversy, or virality—are illusory, detached from any authentic interaction. They’re “talking to themselves” and “pretending to be other people,” as you said, which erodes their own alignment (internal harmony) and authenticity (true self-expression). Psychologically, this might stem from external locus of control, where they believe success depends on manipulating perceptions rather than building real value. The ego gain is the payoff: feeling important in a perceived spotlight, even if it’s self-generated smoke and mirrors.

- Uncharitable Take: They’re architects of delusion, committing real acts of fraud to birth fake empires of attention, all because their fragile selves can’t handle the raw reality of mediocrity. It’s a vicious cycle where deception begets more deception, trapping them in a web of their own making.

4. Broader Implications: Why This Matters in Life’s “Perception vs. Reality” Struggle

- Psychological and Philosophical Tie-In: Humans constantly grapple with what’s real vs. perceived—think Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, where shadows (perceptions) are mistaken for truth. In modern terms, social media exacerbates this via filter bubbles and echo chambers, where curated illusions feel real. Influencers who sockpuppet contribute to this distortion, undermining collective trust and authenticity. For them personally, it might lead to impostor syndrome or burnout when the facade cracks (e.g., exposure scandals), but that’s self-inflicted karma for prioritizing ego over integrity.

- Unpacking Motivations Revisited: As we discussed earlier, narcissism drives the need to control perceptions, Machiavellianism justifies the deceit, and insecurity fuels the fear of unfiltered reality. They’re not achieving alignment; they’re splintering their identity across fake personas, creating a misaligned mess where actions serve illusion over truth.

- Uncharitable Take: In the grand theater of life, these influencers aren’t heroes or even tragic figures—they’re villains in their own story, peddling perceptual poison for profit, reminding us that some people would rather rule a fake kingdom than face the real world as commoners.

In essence, this behavior highlights how real actions can engineer false perceptions, turning the digital stage into a hall of mirrors. It’s not a harmless illusion; it’s active deception that cheapens genuine human connection.